On 27 April 1823 an Edinburgh cobbler lay ill and despondent in his small, bamboo hut in a jungle clearing on the Mosquito Coast.

He sat up, loaded his horse pistol ‘to the muzzle’, and shot himself in the head. The doctor who had been treating him wrote in his diary that he had ‘literally blown himself to pieces’.

Three months earlier he had left Leith docks on a ship, along with 200 jubilant men, women and children, to what he believed was a new life as the official shoemaker to a South American princess.

However, the dream soon became a nightmare. Instead of arriving in the promised land, the would-be settlers found themselves in a tract of inhospitable jungle, a tropical, disease-ridden hell – victims of one of the most elaborate and vicious hoaxes in history.

In the summer of 1821 London society was wowed by the arrival of a Scottish hero of the Venezuelan struggle for independence and the Napoleonic wars. Claiming to be the Chief of Clan Gregor and a direct descendent of Rob Roy, Sir Gregor MacGregor cut an impressive figure. Along with his wife, Josepha, a beautiful and articulate Spanish-American who was a relative of the South American revolutionary Simon Bolivar, they soon became the most sought-after dinner guests in town.

MacGregor’s connections with Bolivar and General Francisco de Miranda, both lauded for their attempts to loosen Spain’s grip on South America, allowed him to be introduced to the right people in London. MacGregor had risen to Brigadier General under Miranda. He also apparently served under the Duke of Wellington in the Peninsular War, and also fought against Spain along the coast of Florida.

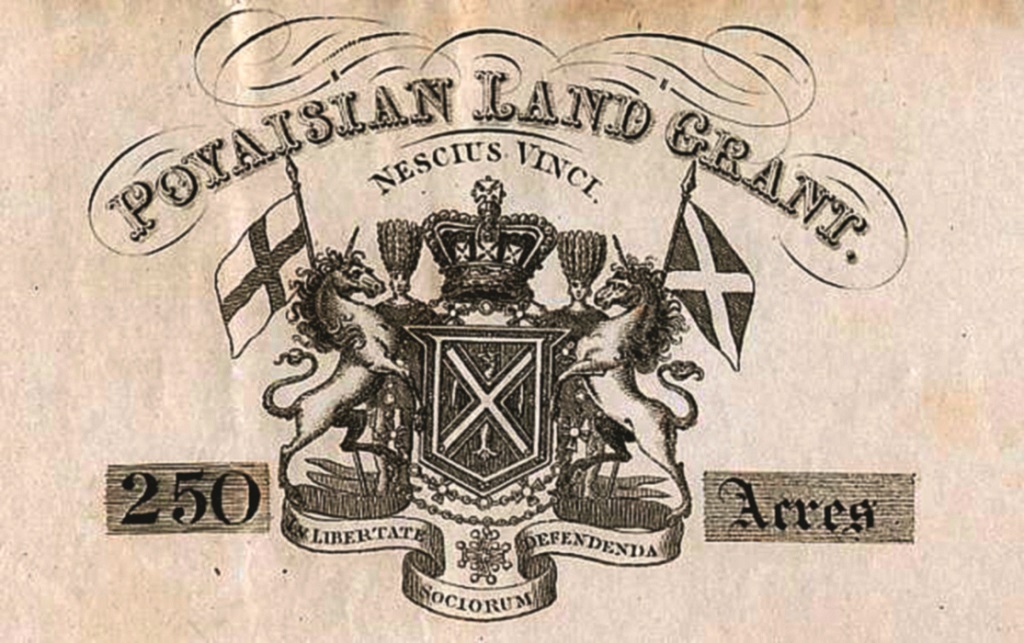

MacGregor was keen to discuss his position as His Highness Gregor, Cazique – the equivalent of prince – of Poyais, on the Bay of Honduras, in South America. Apparently the land, which comprised 12,500 square miles, was granted to him by the anglophile King George Frederick of the Mosquito Coast Shore and nation – he even had a handwritten land grant to prove it.

As MacGregor explained, the country already had a democratic government, a rudimentary civil service and the makings of a small army, and his purpose for visiting Britain was to recruit officials for the government and to encourage immigration by people with the skills to exploit the country’s riches.

MacGregor also claimed to be motivated by a desire to make up for the financial and personal losses suffered by many Scots at Darien, the ill-fated attempt to establish a colony in Panama in the 1690s.

Poyaisian land offi ces were established in Edinburgh, Glasgow and Stirling, where land rights and commissions in the Poyaisian army were sold and positions in the fledgling civil service, legal and financial industries were up for grabs. Doctors, unskilled workers and servants were also encouraged.

MacGregor produced a wealth of convincing promotional material, including newspaper articles and adverts, pamphlets, handbills and even a street ballad. There were also maps and a 350-page guidebook, Sketch of the Mosquito Shore, including the Territory of Poyais, by Captain Thomas Strangeways.

There was also an engraving of the capital, St Joseph, which, the guidebook explained, had been established by British settlers in the 1730s. It was a place of broad, tree-lined boulevards with colonnaded buildings, a domed cathedral, opera house, theatre bank and parliament which housed merchants who had been made rich by Poyais’ abundant natural resources: rich, fertile soil, a kind climate and a ready, hard-working and loyal native workforce.

MacGregor claimed his wife was related to South American revolutionary Simon Bolivar

By the end of 1822 enough settlers had signed up, many using their life savings to do so, to fill seven ships. With a £200,000 loan on behalf of the Poyais government – secured with 2,000 £100 bearer bonds – MacGregor was, in today’s terms, a multi-millionaire.

On 22 November 1822 the first ship, Honduras Packet, left London with 70 emigrants on board. Two months later a second ship, Kennersley Castle, left Leith with a further 200 passengers, including sawyer James Hastie and his family; Andrew Picken, the new manager of the National Theatre of Poyais; and the poor, Edinburgh cobbler, who had left his wife and children behind with a view to bringing them over once he had found a suitable place to live.

Before the ship left, it was visited by MacGregor himself, who brought a chest of Poyaisian currency, for which many on board exchanged their few remaining pounds. He also announced that the fares for women and children were to be waived before he left the boat with jubilant cheers ringing in his ears.

In March 1823 Kennersley Castle finally made it to the Bay of Honduras. But, as James Hastie later wrote: ‘We were very much disappointed to find no town, houses, nor people, except a part of the former settlers, some of them still in tents, and some in houses, or huts, made of bamboo, and thatched with reeds.’

Sure that there had been some mistake, the settlers allowed their ship to sail away, confident that with almost a year’s worth of supplies, a plentiful supply of fresh water, a jungle teeming with fruit, wild pigs and quail and a river full of fish, that they could make a go of it.

However, with a lack of leadership, order in the camp quickly disintegrated. Only a handful of settlers made any real effort; many of the ‘gentlemen’ settlers refused to work, preferring to go off into the jungle to shoot instead. It

was not long before supplies dwindled and the settlers began arguing amongst themselves.

To add insult to injury, on 1 April the settlers received a visit from King George Augustus, who explained that because MacGregor had assumed sovereignty, he had revoked the land grant. It was at this point that any remaining optimism dissolved into despair. By mid-April, when the rains came, the camp was in disarray.

Gregor MacGregor invented the land of Poyais

Many had simply given up: ‘In spite of every exhortation,’ wrote Hastie, ‘some would not exert themselves to get their huts made water-tight.’

Along with the monsoon rains came malaria and yellow fever. On 25 April, one doctor noted in his diary that: ‘Of 200 individuals, all were sick, with the exception of nine.’ People began to die, including one of Hastie’s children.

In an attempt to find help, one of the settlers was eaten by an alligator whilst attempting to swim across the bay. The day after that was when the Edinburgh cobbler shot himself. Before he died he asked the doctor to ‘take charge of his little property, and of a letter to his wife’.

Finally, at the end of May, the jungle was finally breached and a ship was found to take the sick and exhausted settlers to Belize, where more succumbed to illness.

‘Among the first who died in the hospital was another of my poor children,’ wrote Hastie. Fewer than 50 of the 240 or so made it back to London on 12 October 1823.

The following day the story hit the headlines and MacGregor fled to France, where a couple of years later he narrowly avoided prison for attempting the same scheme. In 1839, after further unsuccessful attempts at selling Poyaisian bonds, a virtually penniless MacGregor moved to Venezuela, dying in Caracas, on 4 December 1845.

Little is known about MacGregor’s early life, other than that he was born in 1786 at Glen Gyle and was the son of a sea captain.

He was not chief of Clan Gregor, or directly related to Rob Roy MacGregor, nor was he a military hero with Wellington or in South America.

As one Venezuelan official wrote: ‘I am sick and tired of this bluffer – this man heaps ten thousand embarrassments upon us.’

One thing is certain though. As the 200 men, women and children who lost their lives, those who suffered intolerably and lost their life savings can attest, Gregor MacGregor definitely wasn’t the Prince of Poyais.

TAGS