Is Jack Vettriano Scotland’s greatest living painter?

The titles of many of Jack Vettriano’s paintings come from songs, films and books: Beautiful Losers, Days of Wine and Roses, Lovers and Other Strangers.

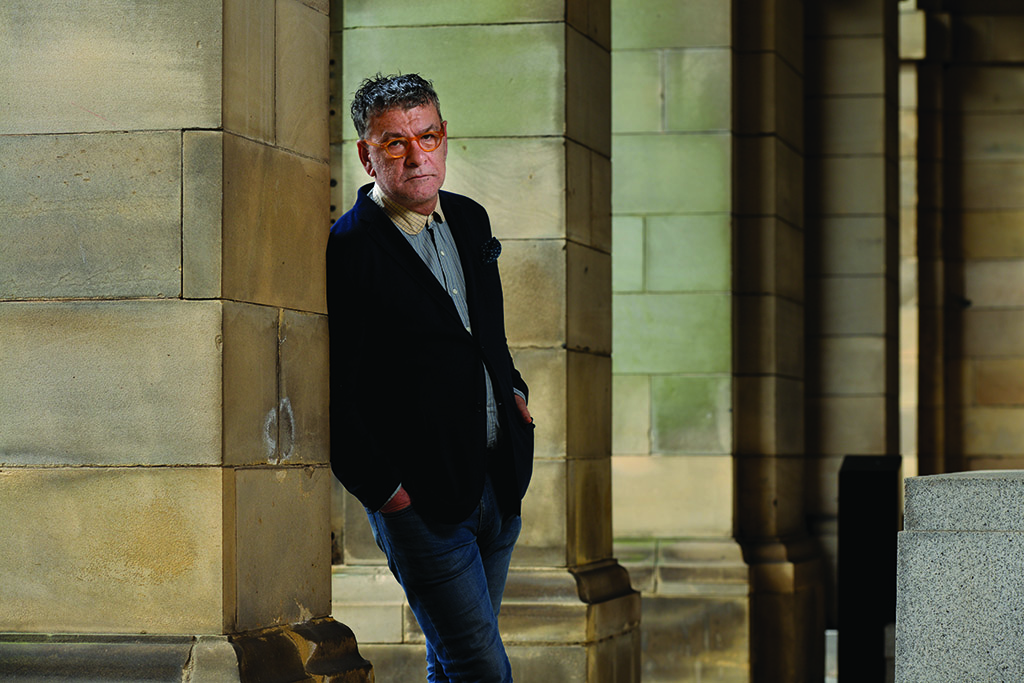

Today, however, the millionaire artist is channelling One Direction. He is wearing skinny jeans. Gone are the dead men’s suits and long hair that were once his signature look. This Vettriano has a close grey crop, statement specs and a jacket that Harry Styles himself might recognise.

‘I’m trying to look younger,’ he admits. ‘If I’m honest, sixty was difficult for me. At fifty I felt like Jack Nicholson: “this is the age to be”, I thought.’ Then the hair had to go. ‘I caught a look at myself in the window of Harrods. (The London flat that was his home for fifteen years was just round the corner.) I felt faintly ridiculous. Much as I like Billy Connolly, he should have done something with his hair.’

For someone who owns up to his ‘fair share of vanity’, there is another, practical, issue at play. ‘The men in my paintings are always me. I can’t do myself young any more so I’m having to relinquish my role as lead male model, and I’m loath to give up that position.’

Occasionally one of Vettriano’s models will offer her boyfriend as an alternative. This is out of the question. ‘I’m too jealous. The guy will look like Clark Gable. I’ll look at a photograph and say “no, I don’t like his nose”.’

Jack Vettriano on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile (Photo: Angus Blackburn)

Vettriano’s younger self was much in his mind when he spoke to Scottish Field in 2013. At the time, a retrospective at Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Art Gallery was drawing the crowds, where he came face to face with some of his older paintings for the first time in decades.

‘I was almost in tears seeing some of it,’ he says. ‘I’ve always been a wee bit embarrassed about my early work.’ He grimaces. ‘It’s limited. But I’ve come to realise that of course it’s limited. It was done twenty years ago. If you don’t improve in twenty years, what the hell are you doing?

‘Of course I would do it differently now. But it’s got a certain charm, a naivety that the new work doesn’t have. People used to say that I couldn’t paint eyes and that was why everybody has a hat on.’ He laughs. ‘To a point, that was actually true.’

Although the sunny end of Vettriano’s oeuvre is familiar from a million calendars, notebooks and framed prints, the Kelvingrove show was the first time most people have had the chance to see the originals.

This show is a huge deal for the self-taught artist, who was born in Methil and turned down by Edinburgh College of Art but still gave up his job as a mining engineer to paint. Through out his career, his work has been eschewed by public collections and the art establishment. Instead, his paintings hang in private collections (Tim Rice, Terence Conran, Alex Ferguson, Jackie Stewart and Alex Salmond are among his buyers) and, in various mass-produced formats, on walls all over the world.

A casual Jack Vettriano (Photo: Angus Blackburn)

The younger Vettriano, with the long hair and nostalgic, optimistic subject matter, was enraged by his lack of critical and curatorial recognition. His most famous piece, The Singing Butler, which went at auction for £744,500 in 2004, has sold ten million copies worldwide. The royalties from that image alone are enough to keep him in designer denim.

Today the older artist seems to have wearied of that particular fight, although he still suspects that it is subject matter, rather than technique, that upsets his naysayers.

‘In some quarters I’m taken with a pinch of salt. They say, “That’s Benny Hill – we’re not interested in Benny Hill”. Well, I am. There is no difference between that and what Jeff Koons [the controversial American artist] does. My work is more relevant and touches the public more. You may look at my work and want to stay in it. You may want to go in it and just stay in it for a wee while, but you identify with it.’

The world of Jack has a certain louche appeal. In it, immaculate women drink champagne and smoke cigarettes at all times, even when bathing or painting their nails. Sturdy black tights, comfortable footwear and thicker knickers are banished in favour of evening gowns, cocktail dresses, dangerous heels and lingerie that should surely be illegal. Men – unless they’re holding umbrellas or mixing cocktails – are lupine, predatory, shadowy figures. It is an adult universe in every sense of the word.

The Singing Butler is Jack Vettriano’s most famous painting (Image: Jack Vettriano)

He gets letters from admirers who tell him they remember specific women he has painted. One came from a retired military man claiming that he knew the butler in The Singing Butler. He had served with him in North Africa. At this

the artist shakes his head. ‘No, you didnae.’

Another of his correspondents, a couple from Luxembourg, outlined the way that they plan assignations based on his paintings. ‘They each have a copy of my book. They email each other: page 43. Then they meet in a hotel, he’s dressed like the guy and she’s dressed like the girl.’ He pauses for one of his wolfish grins. ‘How nice to be responsible for a couple’s happy sex life.’

Sometimes he calls it wrong. Asked to design the First Minister’s official Christmas card in 2011, Vettriano’s first version featured a slinky Santa with nothing but festive cheer to keep her warm. This was deemed unsuitable for sending to the Queen and the Moderator of the Church of Scotland.

Weary of Knightsbridge, Vettriano is considering a return to Edinburgh, where the kingdom of his birth is a quick, free drive away.

‘In spite of where I live, I’ve never really left Fife,’ he says. ‘I’m still petrified of going into restaurants because I don’t know where the toilet is.’ He maintains this is true, and does a plausible imitation of a 60-year-old man in tight jeans having to ask a terrifying maître d’ to direct him to the little boys’ room.

‘It’s a working-class mentality. I quite welcome it; it keeps you down. It reminds you of who you are and how lucky you bloody got.’

- This feature originally appeared in 2013.

TAGS