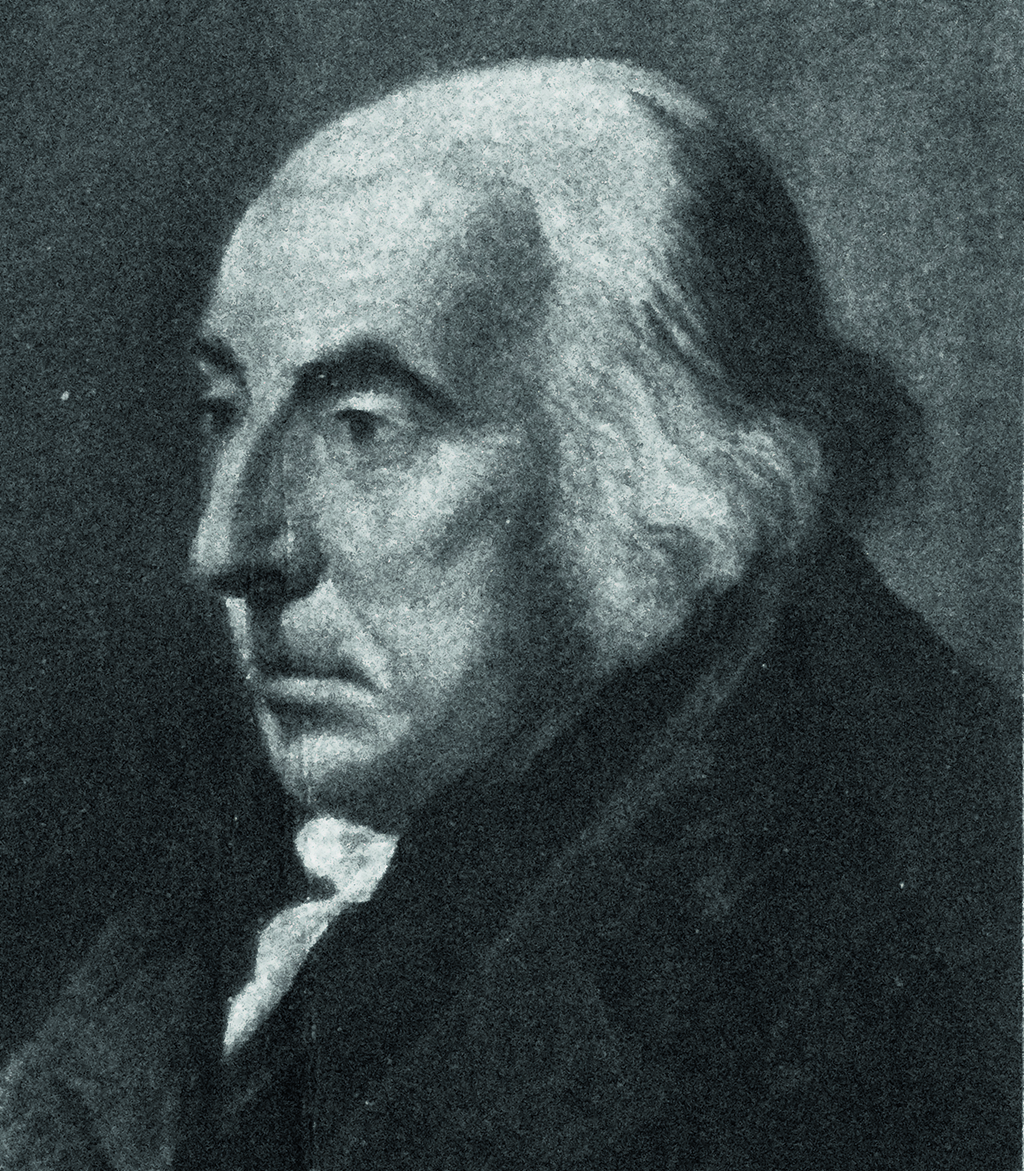

Catherine the Great’s favourite architect was the brilliant, mysterious Scot, Charles Cameron.

Charles Cameron came from mysterious beginnings, origins which he deliberately made foggier. By his mid-thirties, in 1779, without ever having created a building in his life, he was appointed by Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia, to lead a classical architectural revival.

Talented and inventive, and held in awe by his contemporaries, Cameron would go on to become one of the great architects of Russian classicism. Perhaps because many of his buildings were destroyed by the advancing Germans in the Second World War, he is barely remembered in Britain.

In Russia, though, his reputation still stands high.

Much about this passionate, difficult and unusual man is unknown. He claimed to have Jacobite origins and kinship to Cameron of Lochiel, but in reality he was the son of a London builder who came from Scotland.

Nevertheless, he used the claim of grand origins to good effect, and was autocratic and loftily disdainful to Catherine’s courtiers. As the Empress’s appointed builder, he ignored all officialdom, studiously avoided learning Russian, and was prone to the moody outbursts of a distracted artist.

Charles Cameron

Cameron, born around 1745, had launched himself on the world by publishing a book on the subject of Roman baths. It took him five years to produce it, including a lengthy stay in Rome; it was published in a limited-edition of 50, and subsequently reprinted twice. This resplendent, large-format tome, written in both French and English, was full of accomplished drawings and quotes from Greek and Roman writers. It eloquently discussed classical structure, decoration and style, and it is said that working on it provided Cameron with an education.

The book was widely admired and soon reached the Russian court and Catherine the Great. Describing Cameron as a ‘great expert on antiquity’, she summoned him to St Petersburg in 1779, a move that broke the monopoly of architects from Italy. Once there, she installed him in a fine residence, and opened discussions on what she wanted him to do.

St Petersburg had been founded by Peter the Great just 75 years before. Its early buildings, on the banks of the mighty River Neva, were designed in the traditional baroque style.

Cameron introduced a new theme, his version of ‘classical eclectic’. Catherine, who showered her favourites with jewels and estates, wanted a backdrop to a court life that was characterised by ceremony and sumptuous style; Cameron would create the stage set for her benefactions. In her private apartments, cosy elegance was preferred to grandeur. Some of her rooms are renowned. Her personal study, for example, was entirely decorated in silver, while her bedroom had strips of glass laid over purple felt, flannel on the walls and parquet floors.

Enamels made in Russia were deployed alongside elaborate plasterwork and Wedgwood plaques.

Cameron designed much of the palace at Baturyn in the Ukraine

The Cameron Gallery, which led off from her private apartments, is one of the only Russian buildings still called after its creator. Tsarskoye Selo, which established the architect’s reputation, was a village 15 miles south of Petersburg and the imperial family’s summer residence. Cameron’s buildings were stately and graceful, and each was markedly different from the others. He used an array of materials, including valuable stones, china, glass, and lacquer.

At that time architects designed every internal detail too. His walls might be draped in Oriental silks, or adorned with ornate plaster friezes and curling foliage. Sparing no expense, Cameron raked the western world, Italy especially, for artefacts and materials.

Catherine was entranced. She embraced the romanticised persona he had created, claiming he was raised in Rome at the court of the Pretender. When eventually she was pressurised into appointing a commission to oversee her headstrong architect, it reported that his structures were ‘meticulously built’.

To hasten completion and get the skilled finishes he required, Cameron advertised for craftsmen from England and Scotland. A team of 70 specialists was ferried over; he paid them himself. A perfectionist by nature, Cameron demanded an immaculate standard; rebuilds and remakes were imperiously ordered. Two of his Scottish craftsmen, Adam Menelaws and William Hastie, went on to distinguish themselves in Russia in the post-Cameron era. His team, housed in his model village of Sofiya, was called the ‘British colony’.

In style Cameron recreated what he called ‘the old and true method of building’. Palladio was pre-eminent in his pantheon of preferred contemporary architects, and some describe his work as ‘neo-Palladian’. His buildings were intensely decorated without being fussy. He did not rely on scale for grandeur, but rather on proportion and contrast.

The Cameron Gallery at Tsarskoye Selo is adorned with statues of foreign poets and philosophers.

What dazzled contemporaries was his shift from concept to concept, each building deftly suited to its setting and none repeating themselves. At

Tsarskoye Selo, a place of central importance for Russian culture, he also constructed and designed gardens, a model village and incidental palaces.

His two-storey building for bathing was Roman in concept. There were hot, tepid and cold bathing areas, the various rooms linked by marble halls. The floor of one was half mahogany and half mother of pearl. His garden at the model village of Sofiya linked pavilions, statuary, lakes and avenues of trees, glades, and vistas, creating what art historian Dmitri Shvidkovsky called ‘one of the most interesting ensembles of the age of the Enlightenment’.

At Pavlovsk, Cameron laid out the largest landscaped park in 18th-century Russia. Using the principles of William Kent in England, he carefully placed temples and pavilions to create a sense of perfection and harmony. To obtain this effect, he deployed statuary, columns and elegant bridges, even using artificial ruins and historical fragments to create a sense of history

and past times.

The Pavlovsk Palace, for Catherine’s son Paul, came after the park. Containing a Grecian hall and a sculpture gallery, and finished in 1796, it is described by art historian Tamara Talbot Rice, herself Russian, as providing Europe with ‘one of its most perfect smaller palaces’.

Catherine the Great of Russia

When Catherine died in 1796, Cameron was immediately sacked by Paul, and although he worked in Petersburg thereafter, his commissions were of minor importance.

Cameron’s genius has been described as a combination of Scottish dourness and classical scholarship. He was able in his buildings and landscapes to create an alternative universe, imbued with an air of dreamy harmony. Some consider the self-proclaimed Scot to be greater than either of the Adam brothers. Russia gave him the chance to express his talents on a grand scale, and as the Empress’s personal architect he was protected from the social formalities which he fell foul of when in England and from his own touchy temperament.

Although many of his buildings were destroyed in the war, some have been carefully reconstructed. All were properly recorded and listed. One of his intact legacies lies at Baturyn in present-day Ukraine.

Scotland is not by any stretch of the imagination presently in a golden age of architectural glory, and even the heroes of its past are being forgotten. It seems ironic that Cameron’s name in Russia remains undisputed as the great exponent of architecture in the Romantic age. In the country he described as home, though, he is unheralded. It is time he was brought back into the fold, as a part of the Scottish Enlightenment.

- This feature was originally published in 2014.

TAGS