The Scotsman whose art brought Egypt to the world

David Roberts started a Middle Eastern vogue and his art remains highly sought after, but the much-loved Edinburgh artist’s charmed life hid heartbreak and a love that never died.

When the Scottish artist David Roberts collapsed on Berners Street, London in November 25 1864 and died ‘of apoplexy’ that same night, he departed a worldly and well-loved man.

One of the great and good of the metropolitan world, Roberts numbered Turner amongst his very good friends and Dickens and Ruskin among his wider circle. So admired were his architectural watercolours and drawings that even Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were among his patrons, commissioning him to record the Crystal Palace.

But Roberts was not just a friend of Dickens, he was a figure who might have sprung from his pages. Behind the jovial, clubbable Scotsman on the make was heartbreak and economic struggle. He was a man who was born in impoverishment but died in wealth and fame; an apprentice house painter who became a celebrated artist; a Presbyterian by temperament who made his name painting the cathedrals of Catholic Spain and the mosques of Cairo. He was a man, too, who married for love and rued it later.

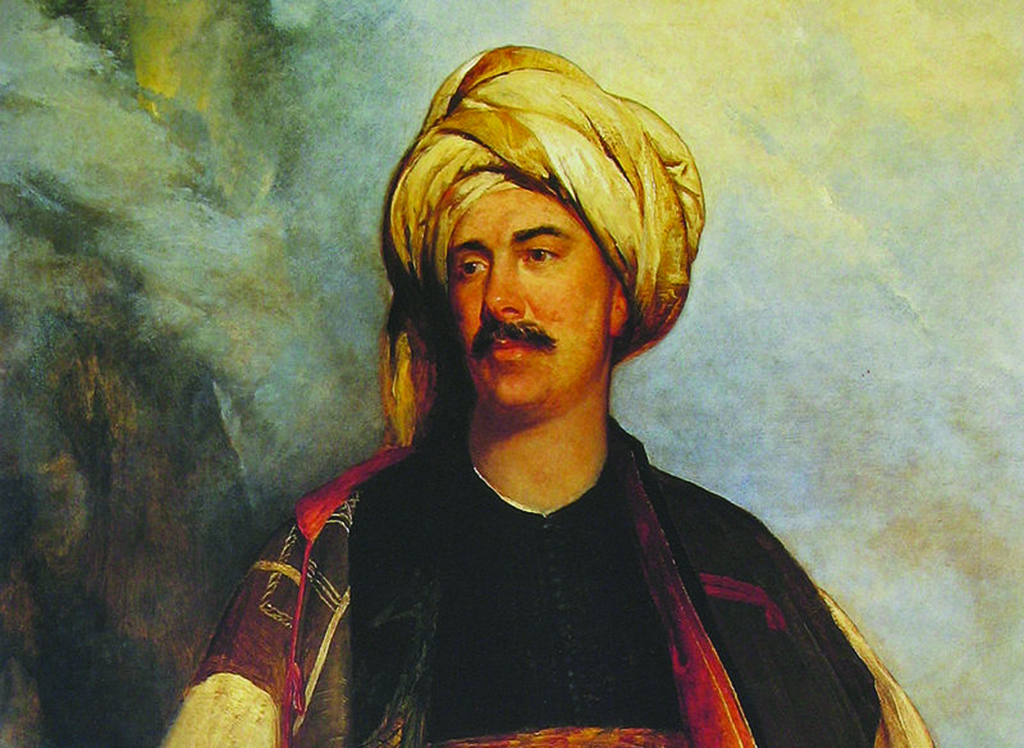

David Roberts Esq. in the Dress He Wore in Palestine by Robert Scott Lauder (1840)

Krystyna Matyjaszkiewicz, a leading expert on Roberts, believes that it was his early poverty and the trials he experienced in his marriage that drove him to succeed. ‘He came from a very humble background, one of seven children. When people have to struggle to achieve things there is a resilience there.’

Matyjaszkiewicz has carried on the research of Helen Guiterman (1916–1998) who was the leading expert on Roberts’s work and who bequeathed a collection of his works to the National Galleries of Scotland. Her thirty years of research into his art and life helped to re-establish his artistic reputation.

Roberts was born on October 24, 1796, the son of a Stockbridge shoemaker who had fallen on hard times and was thus reduced to ‘a mere cobbler’. His mother, who had been in domestic service, took in washing. He went to school at eight, but when his exceptional talent for drawing became apparent, his parents were persuaded that a more conventional artists training would not be suitable for a child of his poor background. He became apprenticed to an Edinburgh house painter Gavin Beugo at just 10 and a half.

As an apprentice, he moved on from stirring foul smelling paint in the workshop for a couple of shillings a week to painting the complex decorative effects of oak grain and marble that would later characterise his architectural works. In his late teens he would work in fine houses like Scone Palace. But like his close friend David Ramsay Hay, who became an art writer, he dreamed of more and of moving on.

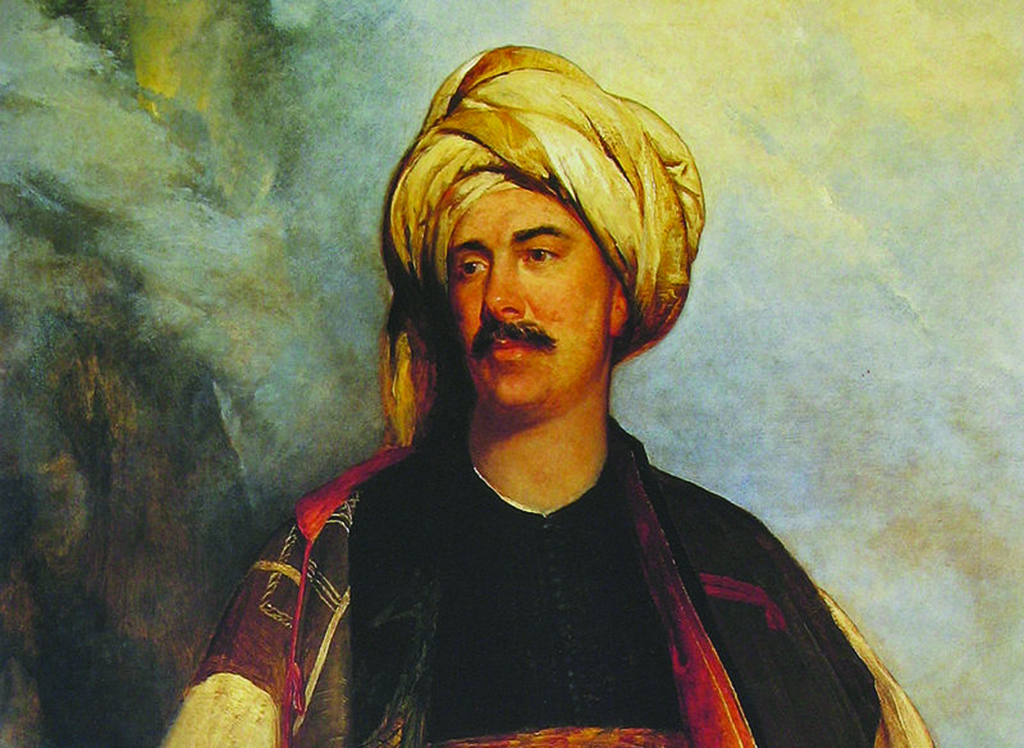

The Statues of Memnon, Thebes, a watercolour by David Roberts

The first chance came with James Bannister, an Edinburgh impresario who himself moved up from variety and animal acts at the Circus on Nicholson Street to a ‘pantomime’ or band of strolling players. When Roberts signed up – his audition was to paint some small pieces on Bannister’s dining floor – he was to make himself useful to the company as required.

They could barely afford to retain a full-time scenic painter, and so he was an actor too. He was a ‘ham’, he later recalled, getting so worked up in once scene that it was said he had shot a fellow player with a pistol, although luckily it was not loaded.

On the move in provincial theatres Roberts would learn a new trade, as well as more about topographical art. He learned business the hard way too, for the records show that he once made his way seventy miles home to Edinburgh on foot after going unpaid in Ayr.

But it was in Glasgow, while working at the Theatre Royal, that his life changed. He fell in love with Margaret McLachlan, a pretty 19-year-old orphan brought up by her extended family. Roberts married, ‘like a true painter, for pure love’ in July 1820, and their daughter Christina was born in June 1821.

In 1822, determined to make more of his life he set sail for London, beginning a new life working for the Drury Lane Theatre. Margaret and Christine soon followed but as he grew more established, submitting works for exhibition and travelling on sketching trips to the continent, his personal life crumbled. As he climbed the greasy pole of advancement, Margaret, who may have struggled to adjust to her new life, slipped further and further into alcoholism.

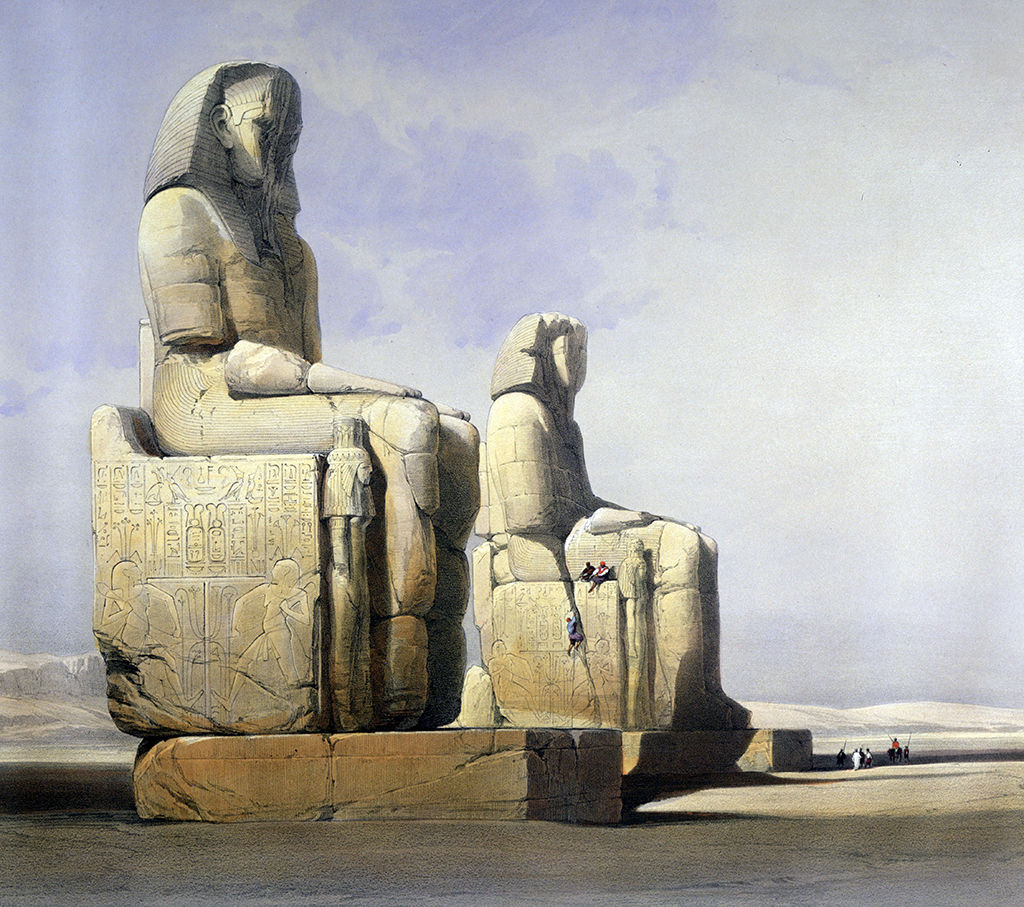

The Great Sphinx and Pyramids of Gizeh (1839) by Roberts

It was the trouble at home, believes Matyjaszkiewicz, that drove his career. ‘His wife was the great love of his life,’ she says. ‘When it went wrong, he threw himself into life and campaigns but it broke his heart.’ In 1832, after 12 years of marriage, he made arrangements for the care of Christina and set off for a trip to Spain that would change his career forever.

He recalled the desperate situation in his own will: ‘About twelve years after our marriage I was compelled in consequence of [my wife’s] abandoned and drunken habits and in order to save myself and my child from utter destruction to break up my Establishment at 8 Abingdon Street and after placing my wife with her friends to leave England….I took her back but she however relapsed into her former habits.’

It was in the colourful cathedrals of Catholic Spain that the avowed Presbyterian honed his style. Roberts knew from the theatre how to pump up dramatic effects of light and shade, how to place figures in interiors and landscapes.

In Spain, he stayed well off the beaten track, and survived an accident in which his coach lost its wheel. He reached Gibraltar and Morocco but a cholera epidemic drove him home after a year.

These days if you think of Roberts, you probably think of his drawings and prints of Egyptian antiquities and the holy sites of the Middle East.

David Roberts in 1844, photographed by Hill and Adamson

Nick Curnow, head of fine art at auctioneers Lyon and Turnbull, confirms that it’s the oriental subjects that sell best. In 1838 Roberts became the first independent British artist to travel to the region. His trip took him to the Pyramids at Giza, Luxor, Karnak and Abu Simbel. In 1839 he went on to Jerusalem, Jaffa and Petra. His early life stood him in good stead. ‘With the exception of mosquitoes, myriads of flies, fleas, bugs, lice, lizards and rats, I was tolerably well off,’ he wrote about his trip.

The results were an artistic and popular sensation. His publisher Francis Graham Moon was to publish six volumes of prints, The Holy Land, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia (1842-9) that paid off handsomely. Even today tour operators and travel companies use Roberts’ highly evocative images to sell their products.

His career made, now a Royal Academician and a patron of the arts, he threw himself into a London social life, but he regularly visited Scotland, campaigned on heritage issues and threw open his home and contacts book to young Scottish artists trying to make it, as he did, in London.

Roberts never remarried, but he stayed close to Christina and her family. He supported Margaret (although not with a messy legal dispute) until her death in July 1860. ‘I loved her to the last,’ he wrote to his close friend Hay, ‘and I have every reason to believe she knew it.’

TAGS