Throughout history, Scotland’s gentry have lost their homes, land and sometimes their entire estates, all for the sake of a wager.

History provides some fascinating examples of the extravagant and often outrageous behaviour of Britain’s landed elite.

Many of these tales surround the gambling exploits of these colourful characters, but there is a darker side. For a number of Scottish landowners, an addiction to gambling led to the dismantling, and in some cases the total loss, of their estates.

For many Scottish estates, debt was due to a combination of bad investment and traditional gambling pursuits such as horseracing and card games (faro, a simpler version of poker, was particularly popular amongst the upper classes), but it was the latter that, for some, could become an addiction and threaten their estates.

In the late seventeenth century, Robert Campbell, the 5th Laird of Glenlyon found himself in serious financial difficulty due to the cost of improving his Perthshire home, Meggernie Castle, and the debts resulting from gambling. In an attempt to clear these debts, Campbell sold the woods at Glenlyon, which formed part of the Great Caledonian Forest.

Tantallon Castle

The felled trees were transported down the river Lyon, but the inevitable logjam caused extensive flooding, which only added to the Laird’s problems. By 1684, Campbell had no choice but to sell the entire estate. Similarly, at the end of the century James Douglas, the 2nd Marquis of Douglas, was forced to sell off Tantallon Castle to service his, and his father’s, combined gambling debts.

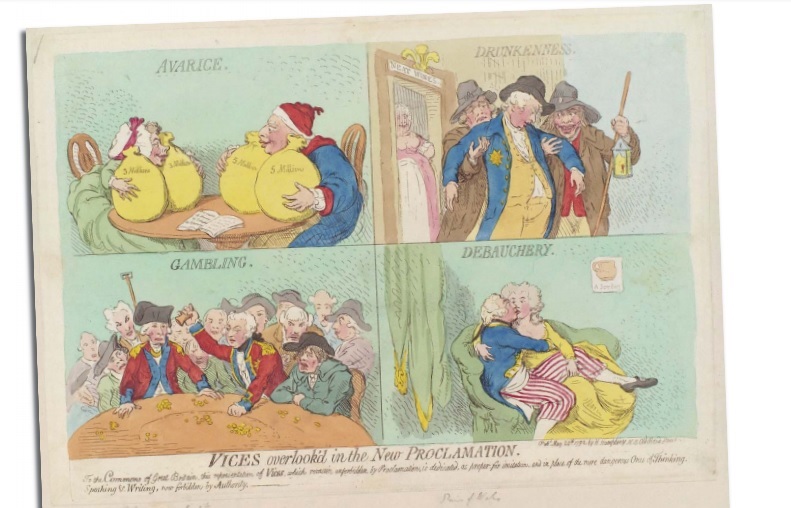

The ‘golden age’ of gambling in Great Britain was undoubtedly the Georgian period (1714-1830) when, according to historian Roy Porter, Scotland was ‘gripped by gambling fever.’ As well as the more traditional gambling pursuits, ‘men bet on political events, births and deaths – any future happenings. For a few pounds challengers galloped against the clock, gulped down pints of gin or ate live cats.’

One such man was ‘Captain Barclay’ – Robert Barclay Allardyce, the 6th Laird of Ury. His most celebrated feat took place at Newmarket between 1 June and 12 July 1809 when, for 1000 guineas, he walked a mile in each of 1000 consecutive hours. The event captured the imagination of the public, and the amount of money wagered was reportedly the equivalent of over £5m today.

This period was also a time of some of the most extravagant and reckless gambling behaviour amongst the aristocracy and landed elite. George IV or ‘Prinny’, for example, had racked up a cool £680,000 in gambling debts by the time he was 33 years old. In today’s money, this amounts to a staggering £22m.

Prinny’s set was notorious for its opulence, extravagance and rakish behaviour. One of the Scottish members of this elite group was William Douglas, the 4th Duke of Queensberry. Famed for his love of the turf, outrageous bets and serial womanising (with a penchant for young, Italian opera-singers), Douglas was also linked to the bacchanal and pseudo-Satanic Hellfire club.

The Duke purportedly bathed in milk to protect his potency, and he is credited with helping to nurture the gambling addiction of the prominent Whig statesman Charles Fox, whose personal debts amounted to around £7m.

A caricature of the gambling King George IV

George Campbell, the 6th Duke of Argyll, was also an inveterate gambler, and not a very good one at that. He was bailed out on more than one occasion by his father, who blamed his son’s debts on ‘very bad hours,’ and believed the best remedy for his gambling problems ‘was marriage’.

The most eccentric Scottish landowner of this period was probably James Carr-Boyle, the 5th Earl of Glasgow. He had an insatiable passion for both betting on and breeding horses, and was equally unsuccessful in both pursuits.

His lack of success was a combination of stubbornness – such as his obstinate refusal to ditch useless bloodlines – and stupidity: he apparently wouldn’t name a horse until it had proved itself a winner. Famously, forced to name three horses he had entered in one race, he quickly christened them ‘Give-Hima-Name,’ ‘He-Hasn’t-Got-a-Name,’ and ‘He-Isn’t-Worth-a-Name.’

It was also not unknown for Carr-Boyle to order horses that performed badly to be shot on the spot – there were apparently six such summary executions in one morning, and such impulsive behaviour was to the detriment of a number of promising bloodlines. As an aside, it was not unusual for the Earl, when foxhunting, if a fox was not forthcoming, to designate one of his huntsmen the quarry, who would be chased relentlessly through the countryside for hours.

Carr-Boyle’s behaviour undoubtedly weakened his estate at Kelburn, on the Firth of Clyde, but largely it remained intact. A number of other Scottish landowners in this period were not so fortunate, however.

In the early 1700s, the 22nd Laird of Hunterston alienated a large portion of his estate near Largs in Ayrshire because of his gambling debtsMore tragically, in 1787 the 13th and last Laird of Gight in Aberdeenshire, Catherine Gordon, was forced to sell the entire estate to Lord Aberdeen in order to pay off the debts of her gambling-addicted husband, ‘Mad’ Jack Byron. By way of thanks, Byron deserted his wife and their young son, the future Lord Byron, virtually penniless in London.

Of course gambling addiction was not just an eighteenth century phenomenon. For example, in 1820, Kilmahew Castle, in Cardross in Dunbartonshire, was sold by Lord Napier to raise the funds to settle his gambling debts, and one of the motivations behind the uprooting of tenants by Highland chiefs and landowners during the clearances in the nineteenth century was apparently to create wealth to service gambling debts.

Perhaps one of the most costly episodes occurred at the beginning of the twentieth century when the gambling problems of Roger Aytoun, the Laird of Kinglassie and MP for Kirkcaldy from 1862-74, finally caught up with him. He declared himself bankrupt, and large swathes of Fife were auctioned off to pay his creditors.

The 6th Duke of Argyll

The gambling debts discussed so far were generally accrued over time, but one of the most singularly impulsive acts of gambling madness can be attributed to a Scot, William Cunninghame Graham of Gartmore, who attributed his gambling addiction to his association with Prinny and his set.

In 1803, during one of his particularly excessive parties, William was having a bad night at the card table. Although he’d lost all of his money, the young Graham was not yet ready to leave the fray. With a true gambler’s faith that his luck would change, he borrowed £1000 (around £32,000 today) from Colonel Archibald Campbell. The surety for this loan was the exclusive use of the family estate, Finlaystone House and its appendages, for the duration of the Colonel’s life.

Needless to say, William’s luck didn’t change, and the Colonel moved in soon afterwards. Whilst this was undoubtedly a wild and reckless act, at least the estate returned to the Graham family on the Colonel’s death in 1825.

Nowadays, Scotland’s estates and castles are often faced with more prosaic financial challenges such as taxes, crumbling edifi ces, and window-cleaning bills. One of the more positive results of these problems has been the opening up of grounds and buildings for our enjoyment.

The next time you visit one of these wonderful country piles, consider how it may have been shaped by the extravagant and often downright foolish, gambling eccentricities of its previous incumbents. Could it have been sold, or dismantled to service gambling debts? Can you really be sure that it wasn’t won in a late-night game of faro at a drunken party? I wouldn’t bet your house on it.

TAGS