April 2016 marked the 430th anniversary of the Massacre of Annock.

Though not an unusual occurrence in the lawlessness of Scotland in the 16th century, that event, and particularly the extent and ferocity of the reprisals that followed, marked the beginning of a change in attitude towards blood feud.

‘Blood feud was the custom of the times.’ So wrote William Robertson in Ayrshire: Its History (1908). Of course, feuding between Scottish clans wasn’t a new phenomenon and it certainly wasn’t confined to Ayrshire.

There were many long-standing feuds between families throughout Scotland, from the Scotts and Kers in the Borders, to the Campbells and MacDonalds in the west, and the Gordons and Stewarts in the Highlands.

But the Ayrshire Vendetta, as it became known, is a classic example; the Cunninghame and Montgomery families were later dubbed the ‘Montagues and Capulets’ of Ayrshire.

Various factors contributed to a culture in which violence was considered the most appropriate manner of dealing with dispute.

Foremost was the weakness of the Crown. Of the seven Scottish monarchs of the 15th and 16th centuries, only one (James IV, aged 15 when he became king) was able to rule in his own right from accession. Of the others, three inherited the throne as infants (James V, Mary, Queen of Scots and James VI) and two at less than ten (James II and III), while James I, aged 12, was captured, still uncrowned, and detained in England for 18 years.

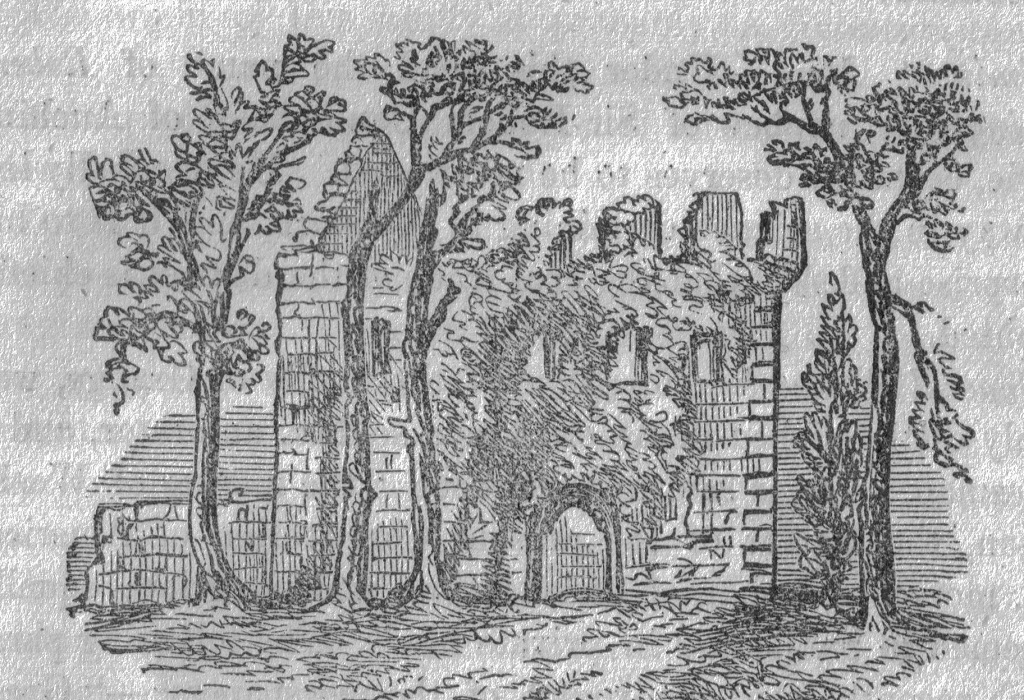

Eglinton Castle as it stood in 1876

As a result, the years of successive minorities were characterised by a nobility jostling for precedence and for control of the monarchy, allied to a general acceptance of the rule of ‘might’ regardless of ‘right’.

On his accession in 1488, James IV set out to establish stable government at local level, appointing representatives in each district to dispense justice. A laudable aim, marred in Ayrshire by an error of judgement when he passed control of the bailiwick of Cunninghame to Hugh, Lord Montgomery, thus sparking the 150-plus-year feud.

Although the original affront had been to the Cunninghames, the first blow in the feud was the sacking of Kerelaw – a Cunninghame tower situated in the midst of Montgomery territory. The years that followed were punctuated by repeated acts of brutality and murder on both sides.

In 1505, Cunninghame of Craigens was attacked and wounded by the Master of Montgomery; and in 1507 the Cunninghames retaliated, attacking the newly created Montgomery Earl of Eglinton, with lives lost on both sides.

Meanwhile, the issue of the bailiwick became the subject of arbitration, the decision in favour of Eglinton in 1509 failing to satisfy the Earl of Glencairn, head of the Cunninghames.

However, as is so often the case when a country is threatened by an external enemy, private grievances are set aside. So it was in the years before Flodden, clans uniting in the face of the English threat. The Scottish losses, whether one accepts the lower estimate of 5,000 or the higher of 10,000, decimated the nobility and left the country once again with an infant king.

It is interesting to note that though both Eglinton and Glencairn were on the same side in the unsuccessful conspiracy to depose the Duke of Albany, Regent for James V, it failed to diminish the ill feeling between the two families.

Kerelaw Castle in Stevenston

Just four years later, in 1517, hostilities flared again with the wounding of John, Master of Montgomery and the killing of his followers. Though Albany extracted an agreement from both factions to lay aside their quarrels, it served only to delay revenge, Cunninghame of Auchenharvie and of Waterston becoming the next victims.

These tit-for-tat murders led to one of the most significant episodes in the vendetta, when in 1528 a large force of Cunninghames rode through Montgomery territory, causing wholesale destruction, decimating crops, stealing and killing stock, and burning the dwellings, leaving the tenantry penniless and homeless.

The raids culminated in the burning of Eglinton castle itself, destroying all the contents, including tapestries, furniture, paintings, armaments and, most important of all, family records going back as far as the Norman Conquest, as well as their Charter to the Montgomery lands.

This time the Montgomery earl, perhaps tired of violence, or feeling his increasing age, accepted a cash settlement as compensation, and for a period of almost 60 years there are no records of atrocities, though whether as a result of external pressures or a genuine attempt at peace, it is hard to gauge.

The external pressures were certainly significant – war with England, the Scottish defeat at Solway Moss and the subsequent death of James V, which resulted in the accession of six-day-old Mary and a new cycle of government by regency. Then came the ‘Rough wooing’ as Henry VIII tried to force a betrothal between his son Edward and Mary, the English incursion into southern Scotland and two battles: Ancrum Moor, where the Scots were victorious, and Pinkie Cleugh where the honours went to England, precipitating the smuggling of the young Queen Mary to safety in France.

But it seems that old enmities are hard to stifle and when the country was once again secure, with James VI on the throne and hopeful of inheriting the English crown, the feud erupted once more, with the massacre at Annock in 1586. This happened when a small group of Montgomerys stopped at Langshaw on route to the court at Stirling.

The Cunninghames, having been alerted to their presence, were lying in wait to ambush them. Though the numbers killed were small, the aftermath was brutal and wide-ranging. As Robertson put it: ‘All the country ran to arms, either on one side or the other, so that for some time there was a scene of bloodshed and of murder in the West that had never been known before.’

Lady Margaret of Langshaw, a Cunninghame by birth but married to a Montgomery, was held responsible for the ambush and forced to remain in hiding for many years – a heavy price to pay for a family name.

James VI, determined to outlaw blood feud, brought forward laws restricting the carrying of firearms, and commanded opposing lords to parade hand-in-hand up the High Street in Edinburgh as a symbol of the new, peaceful order.

It wasn’t quite the end of the Ayrshire Vendetta, for in 1606, while Parliament was in session, a battle of three hours’ duration was waged on the streets of Perth. But in contrast to Shakespeare’s ‘Montagues’ and ‘Capulets’, the marriage of William, 9th Earl of Glencairn to Margaret Montgomery, daughter of the 6th Earl of Eglinton, did finally seal the peace in 1661.

And in an interesting postscript, the Lord Lyon recognised a new chief for Clan Cunninghame in 2013. His name? Sir John Christopher Foggo Montgomery Cunninghame.

TAGS