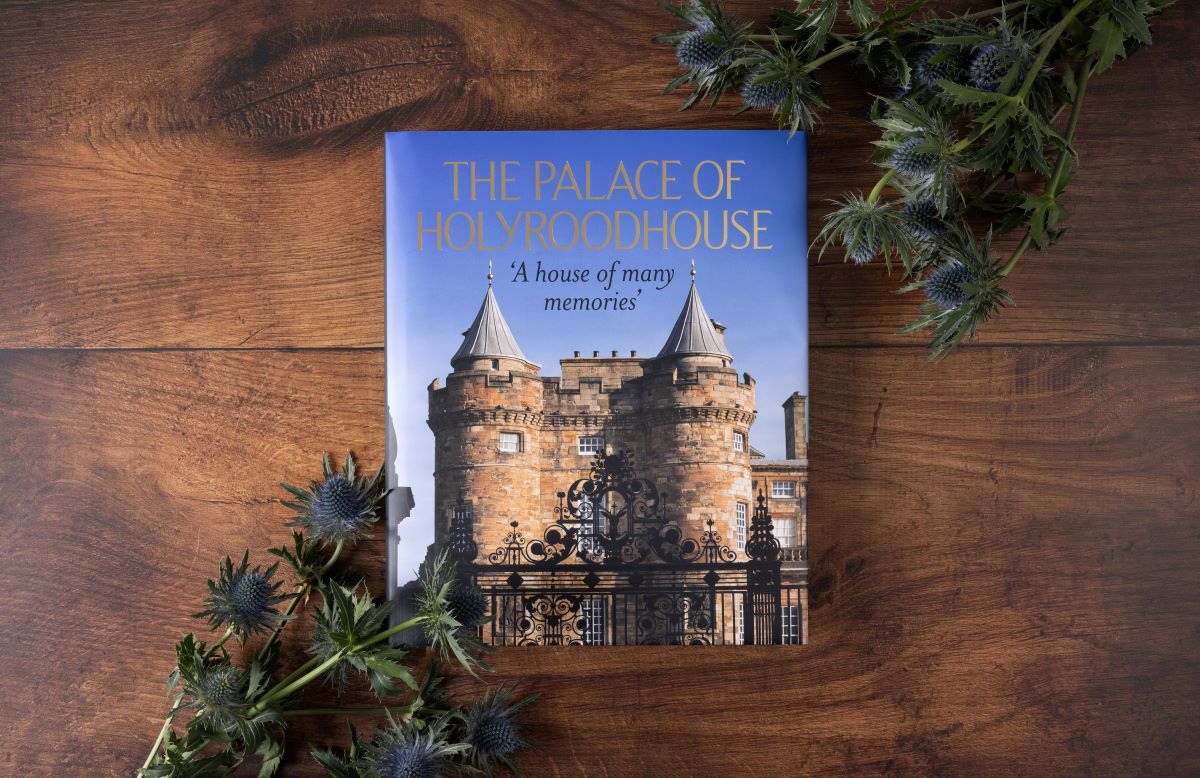

‘If these walls could talk’ might be the most fitting idiom when thinking about The Palace of Holyroodhouse.

It’s journey from 12th-century abbey to official Scottish residence of His Majesty The King is peppered with royalty, glamour and even murder.

Mary, Queen of Scots spent just six years at the Palace in the 1560s, but it was the setting for many of the important events of her reign, including two of her three marriages and the murder of her secretary, David Rizzio, stabbed more than 50 times by her jealous husband and his fellow nobles.

In 1745 Bonnie Prince Charlie occupied Edinburgh and held court at the Palace for six weeks during the final Jacobite rising. The glittering balls that he is said to have held inspired writers and artists such as Sir Walter Scott and Sir John Pettie.

Now its dramatic past has been revealed in the first official history ever published.

The Palace of Holyroodhouse: ‘A house of many memories’ published by Royal Collection Trust is said to be the most comprehensive history of Scotland’s royal palace produced in over 100 years.

© Royal Collection Enterprises Ltd 2024 | Royal Collection Trust.

The book is filled with new research and is richly illustrated with historical drawings, watercolours and photographs.

It also reveals some of the Palace’s more surprising occupants through the centuries – from a Russian princess and a penniless French King to a menagerie of lions and tigers.

The Palace’s origins lie in the foundation of Holyrood Abbey nearly 900 years ago in 1128. In 1503 James IV converted its royal lodgings into a palace, which was expanded further by James V.

Only the north-west tower from this early building survives, and the Abbey – once one of the finest medieval abbeys in Scotland – fell into ruin in the 1760s.

However, a new reconstruction drawing – commissioned for the book using new research and GPS surveys – shows what James V’s lost Renaissance palace and Holyrood Abbey might have looked like for the first time.

New discoveries were made about Bonnie Prince Charlie’s occupation of Holyroodhouse for the Jacobite cause.

During research for the book, a letter came to light, written by the Duke of Perth in September 1745, confirming that a ‘great ball at ye palace’ had taken place two days after the Battle of Prestonpans, probably to celebrate the Jacobite victory.

John Pettie, Bonnie Prince Charlie entering the ballroom at Holyroodhouse, 1892. © Royal Collection Enterprises Ltd 2024 | Royal Collection Trust

It is the only contemporary reference to a specific ball known to exist, confirming that these celebrations were not simply a later artistic invention.

The book sheds light on the Palace’s role hosting foreign royalty in the 18th century. The Russian princess Ekaterina Romanovna Dashkova, a close friend of Catherine the Great, lived at Holyroodhouse between 1776 and 1779 while her son was educated in the city.

She became an influential society figure, hosting weekly dances, and described her time at the Palace as ‘both the happiest and most peaceful that has ever fallen my lot in this world’.

During the French Revolution, Marie Antoinette’s exiled brother-in-law, the comte d’Artois, lived at the Palace for seven years, using the Abbey’s status as a debtor’s sanctuary to avoid his creditors.

His chaplain, valet, cook and other servants were also accommodated at the Palace, and he was soon joined by his sons and mistress.

Following the restoration of the French monarchy, he later succeeded to the throne as Charles X, before being deposed and returning to Holyroodhouse for a further two years.

In 1822 George IV became the first reigning monarch to visit the Palace in almost 200 years.

Mary, Queen of Scots’ Supper Room, where the attack on David Rizzio began. © Royal Collection Enterprises Ltd 2024 | Royal Collection Trust, photograph by Peter Smith.

The book describes the elaborate preparations made by the visit’s organiser, Sir Walter Scott – from the demolition of an entire building to make way for the King’s procession up the Royal Mile, to the meticulous instructions given to those attending events at the Palace.

Ladies were to wear ‘at least nine feathers’ in their headdresses, and must ‘exert their skill to move their trains as quietly and neatly’ as possible after meeting the King; a skill they should ‘lose no time in beginning to practise’.

Queen Victoria felt a profound connection to Scotland and to Holyroodhouse, where she and Prince Albert would stay each year en-route to Balmoral Castle.

The royal couple were captivated by the beauty of Holyrood Abbey, and the book reproduces sketches that they made of the ruined building from their windows, as well as watercolours of their apartments, commissioned by Queen Victoria after Prince Albert’s death to commemorate happier times.

Extensive research into the Palace gardens sheds light on their varied uses through the centuries, from medieval jousting grounds and a royal menagerie, to the foundation in 1670 of one of Britain’s earliest botanic gardens, which later became the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

The ruins of Holyrood Abbey and the grounds of the Palace of Holyroodhouse. © Royal Collection Enterprises Ltd 2024 | Royal Collection Trust, photograph by Peter Smith

The Palace’s story is brought up to date with an exploration of its role in the 20th and 21st centuries, from its first garden party and a lucky escape from wartime bombing, to the opening of The Queen’s Gallery (now The King’s Gallery) in 2002.

The book recounts the moment the eyes of the world turned to Holyroodhouse in 2022, when Queen Elizabeth II lay at rest in the Throne Room after her death at Balmoral Castle, and describes the Royal Family’s use of the Palace today to celebrate Scots from all walks of life.

The Palace of Holyroodhouse: ‘A house of many memories’ is out now.

Read more Book news here.

Subscribe to read the latest issue of Scottish Field.

TAGS