Alexander McCall Smith, whose books are a prescription for happiness, talks about his responsibility to his readers and the female influences in his life.

His kitchen table is hiding beneath the complete works of Yotam Ottolenghi, the current darling of the adventurous middle-class kitchen.

Sandy, as everyone calls him, is on dinner duty tonight and research is proceeding apace. His wife, Elizabeth, is also keen to establish when he will be able to visit the optician and fix the doorbell. The couple’s daughter’s Tonkinese cat is expected any minute.

How, the casual observer might ask, does this man write one, never mind four, books a year? ‘I am,’ he says breezily, ‘breaking all known rules of publishing.’

And that is without considering his tour schedule, which makes the Rolling Stones look like part-timers. Every day of 2014 is booked up, with trips to the United States, Australia and New Zealand taking up months at a time.

‘I am not moaning about it,’ he stresses, once he is removed from domestic distractions and installed in his enviable art-lined study. ‘I am the author of my own misfortune. It is very difficult to keep this under control once you are doing it.’

What Sandy calls his ‘little enterprise’ starts with the annual quartet of novels, some featuring beloved characters Mma Ramotswe and Isabel Dalhousie, others, such as The Forever Girl, standing on their own.

‘These are published in English in London, New York and Edinburgh. Then they are translated into 46 foreign languages including, I am delighted to say, Scots,’ he adds, referring to Precious and the Puggies, his children’s story featuring the young Mma Ramotswe, given the vernacular treatment by the novelist James Robertson and published in 2010.

All of which amounts to a mighty juggernaut of literature and, while that speeds down the international highway of devoted Mma fans and Isabel obsessives, it is, the author claims, ‘quite diffi cult to say I won’t do this, that and the next thing. I have millions of readers. I feel a certain responsibility.’ He smiles. ‘And I have difficulty saying no to people.’

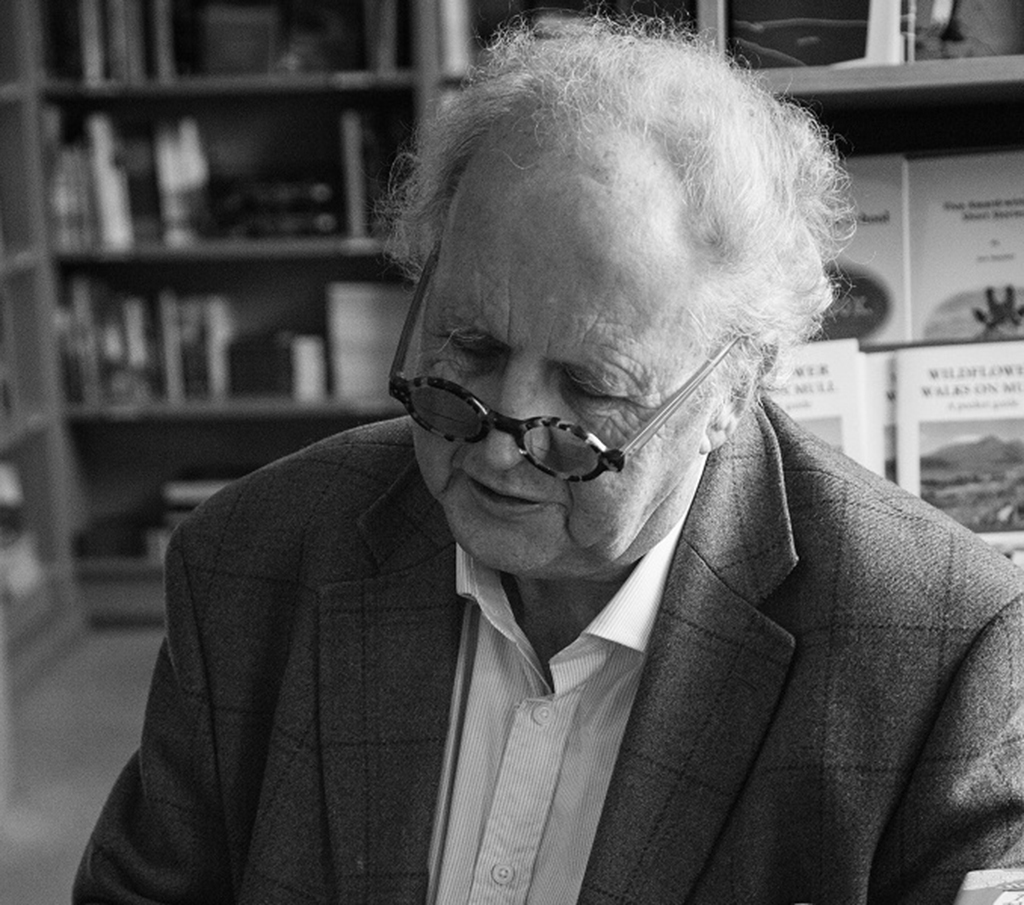

Alexander McCall Smith, pictured in Edinburgh

What is it about Sandy’s books that keep him crossing time zones when other men would be settling down in front of Cash in the Attic? He is 65 and took early retirement from his proper job, as professor of medical law at the University of Edinburgh, in 2005 to write full time.

The answer is simple: he takes his readers to a happy place. Mma Ramotswe may run the No.1 Ladies’ Detective Agency but precious little crime actually crosses her doorstep. Instead, according to the author, ‘She is an agony aunt. The books are about her, her kindness to others, her love of her country.’

Isabel Dalhousie is an amateur sleuth but this series is about philosophy, her bassoon-playing boyfriend and his home town, Edinburgh. The Forever Girl is an old-fashioned love story set in the Facebook age.

‘The philosophical case for optimism and positivity is more convincing than the opposite,’ he says. ‘If we contemplate the world we can see it as a vale of tears and it is a hard and distressing place, full of sorrow. But that should not dictate one’s approach.

‘It’s more diffi cult to write in the major positive key than the minor key. And because it’s relatively easy to write about the dysfunctional, people assume that’s the default position. So I’m accused of being a utopian writer.’

He chuckles. ‘That is regularly wheeled out. There is an expectation that writers are going to be miserable and nasty and cantankerous about the world, and delight in the humiliation of people in hardship. There are writers who are picked by fate to do that but it shouldn’t be the universal position.’

His readers leave him in no doubt they appreciate his efforts on their behalf. He gets letters – many McCall Smith aficionados date back to the age of the fountain pen – from families where his books are enjoyed across generations. Psychiatrists and therapists suggest them to patients. His work has even been mentioned in Netflix TV series Orange is the New Black. One chap noted on the author’s Facebook page that, with two different McCall Smith books on the go at the same time, he had died and gone to ‘comfy heaven’.

These novels are very much safe for work. Sandy may live outside the strict boundaries of Morningside but his books share that douce district’s theory that sex is what the coalman carries over his shoulder. ‘My books don’t have sex in them but there is a lot of erotic tension, which is far more powerful. And there is never any strong language.’

In The Forever Girl – which dots between Edinburgh, London, Sydney and Singapore – one scene is, to the attentive reader, hot stuff, with the author gleefully describing it as ‘quite steamy for me’. Yet he depicts this swimming pool encounter between his smitten heroine and the object of her unrequited affections so deftly that Granny would never notice it was there, never mind choke on her pan drop.

Alexander McCall Smith at a signing

Sandy takes his readers’ sensibilities seriously. ‘I don’t write for them but I am aware of a certain moral responsibility towards them. I couldn’t have anything bad happen to Mma Ramotswe or Mma Makutsi. It would cause such distress to people all over the world.’ He flinches at the very idea. ‘There are people who live their lives according to Mma Ramotswe.’

When he mentioned, at a Texan literary lunch, that Mma’s abusive husband might be coming back, the massed shoulderpads in the audience bristled. You will do no such thing, they drawled firmly. In the face of so much animosity and hair lacquer, he backed down immediately. Further discussion produced a compromise, whereby he was permitted to revive the character, but only if some very nasty things happened to him.

It’s clear Sandy’s worlds, real and fictional, are heavily feminine. He has two grown-up daughters and a female personal support team running the diary and answering his many, many letters. ‘I find the conversation of women interesting,’ he says simply. ‘Casual male conversation is about external things. There are restraints, taboos – men don’t talk about emotions. If you do manage to get men talking amongst themselves about feelings, they don’t like it, they get a bit embarrassed. As a result, a lot of men are very lonely and very isolated.’

Not him, it would seem, surrounded by purring cats and museum-quality paintings, splitting his time between Edinburgh, Argyll and first-class airport lounges. Should he need to escape from all the oestrogen and talk shop, Ian Rankin’s home is just over the fence.

It’s not, he insists, that he is particularly sensitive and well adjusted. ‘I’m just the same as anybody else, fairly average. It’s the business I’m in – the mind, the world, what people are thinking and feeling. When I go into a restaurant, I’m interested to know who the other people are, what their story is. That’s part of being a novelist.’

There is an element, he adds, of ‘downright nosiness’. Given the amount of pleasure he has brought to millions of readers, we can let him off.

Click HERE to read more from Scottish Field’s culture section.

- This feature was originally published in 2014.

TAGS