You know the name… you know the number – James Bond, 007.

As the author of the James Bond novel Solo, William Boyd has shared parts of his own life with Ian Fleming’s eternally popular hero.

Published in 2013, Solo centres on Bond’s mission to the civil war in the fictional country of Zanzarin, where he meets the local MI6 contact, Efua Blessing Ogilvy-Grant, and a Rhodesian mercenary, Kobus Breed.

Boyd closely based his version of the Bond character on Ian Fleming’s, rather than the lighter film version.

I’ve got a theory about William Boyd, although to be completely honest, I should admit it’s one based on something he said the first time we met. If I’m right, it should explain why he’s just written probably the best James Bond novel since Ian Fleming – or even, at the risk of offending the purists, a Bond novel that is better than any Fleming ever wrote.

I first met Boyd at his book-lined Chelsea house ten years ago to interview him about his novel Any Human Heart, which I still consider his masterpiece. It takes the form of an intimate journal written by

his fictional protagonist Logan Mountstuart over the course of eight decades. The novel’s whole point is to show how Mountstuart’s character – inevitably mirrored in his writing style – changes over the years. Our personalities, the book implies, aren’t fixed: we each contain if not multitudes then at least an anthology of different versions of ourselves, each one determined by age and experience.

This strikes me as so obviously true, and has the added advantage of showing us life as we live it rather than as we subsequently rationalise it, that I can’t imagine why more novelists don’t write books in this way.

I asked Boyd whether he’d ever kept such a journal and he said that he had. He’d started one when he was 19, kept it up for a couple of years, then there was a gap of ten years until he resumed it. He still keeps one, although he adds that it is emphatically not written for publication.

‘The only problem,’ he said, ‘is that if you’re a writer and you’re keeping a journal, whatever you write in it is changed just by being a writer in the first place. You look at things differently. So the only experience you can truly draw on – and this is your seedcorn as a novelist – is what happens before you start filtering it through a journal.’

My theory about William Boyd is, therefore, astonishingly simple. If you want to understand his own human heart, you’d do well to look at what he was like before he was 19.

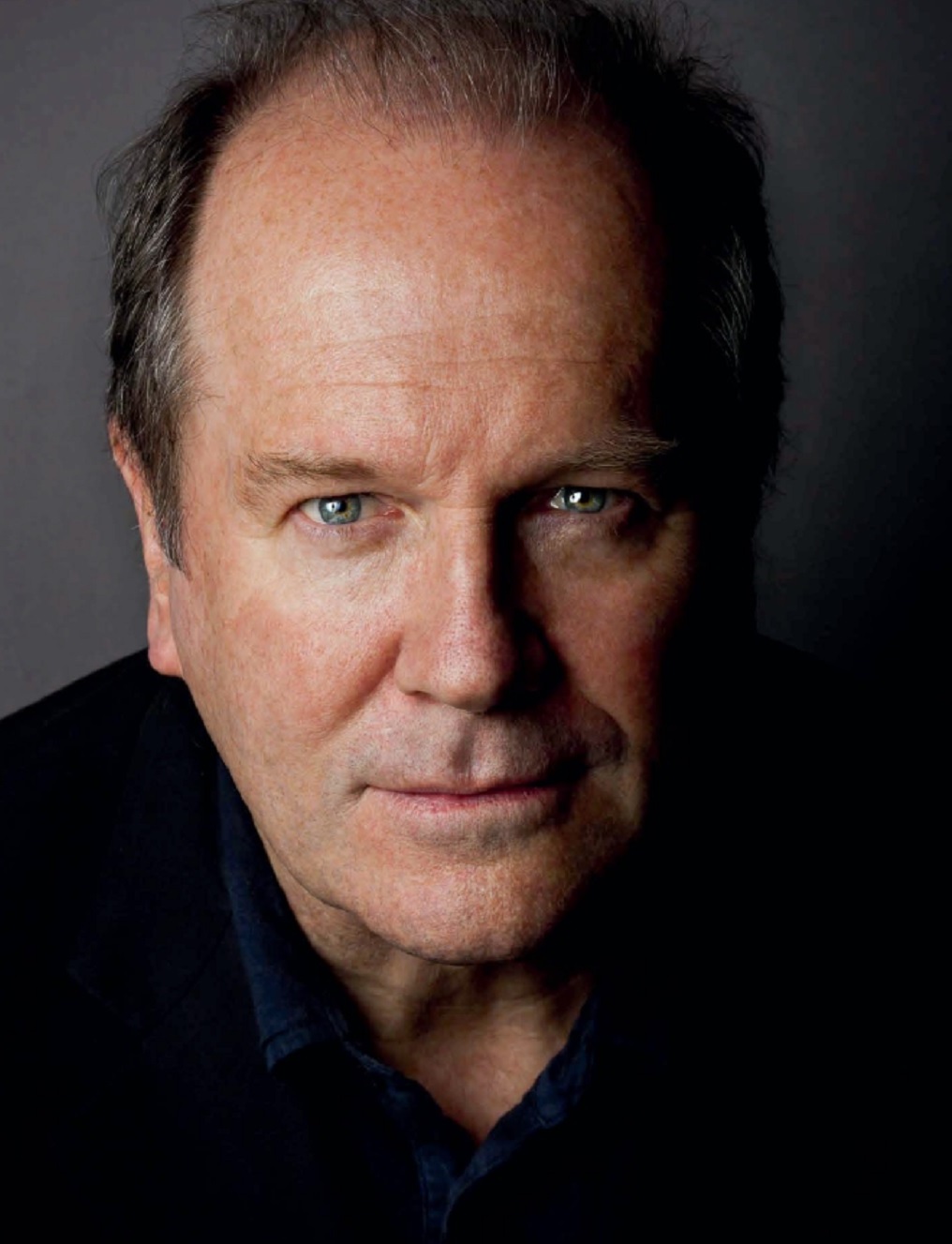

Writer William Boyd

Certainly his Bond novel, Solo, suggests that my theory might be right. Consider the evidence. At 17, Boyd was at Gordonstoun, where he was a contemporary of Prince Charles. During the school holidays, however, he flew back to rejoin his family in Ibadan, in western Nigeria, where his father lectured in tropical medicine at the university. This was in 1969, the third year of the Biafran war, when the oil-rich province of the Niger Delta tried unsuccessfully to secede.

In Ibadan, the Boyds were hundreds of miles away from the conflict. It hardly affected them – although there was one scary incident when his father, with his son next to him in the passenger seat, inadvertently drove through a checkpoint manned by some Nigerian soldiers. ‘They’d been drinking, probably all day,’ Boyd recalls, ‘and as they advanced towards us, guns pointing at us, and shouting angrily, I realised how things could go pear-shaped so very easily, and what a thin carapace our supposedly steady life is actually based on.’

Now all this, remember, is happening in the seedcorn years before Boyd hit 19. Already, at Gordonstoun, he has read Fleming’s Bond books, to which he was introduced by his father. Aged 17, he told me, when we met again last month, he thought of himself as ‘Afro-Scottish’ and felt completely at home with West African culture. There was none of the antagonism towards whites found in eastern and southern Africa, he insisted, for the simple reason that Europeans didn’t tend to settle there and claim the land for themselves.

Now skip forward over four decades. In October 2011, Ian Fleming’s literary estate asked him whether or not he’d like to follow Sebastian Faulks and Jeffrey Deaver in writing a James Bond continuation novel.

‘I didn’t hesitate for a second,’ says Boyd. ‘They asked me where I’d like to set it and straight off I said 1969. And when they asked where I wanted to take Bond to, I also knew straight away: Africa.’ He knew what he’d call it too: Solo – its two Os already indicating a licence to kill, as well as hinting that this is a novel where Bond pursues a mission entirely for himself.

Now there is indeed a scene in Solo, when Bond – accompanied, of course, by a stunningly beautiful fellow agent – is stopped at a roadblock while on his way into a fictionalised Biafra. To say that this is based on that moment of heart-stopping terror Boyd experienced with his father at a similar roadblock – before his father defused the tension by lambasting the soldiers for building such a useless barrier that he hadn’t been able to see it – is obviously to crassly oversimplify, so I’ll just leave that thesis hanging in the air.

James Bond creator Ian Fleming

But I will point out, all the same, that Boyd’s Solo is probably the most Scottish Bond that we’ve seen between book covers, as well as one of the more realistic. ‘In that,’ he insists, ‘I’m just following Fleming. It was he who made Bond spend all of his senior schooldays at Fettes apart from two terms at Eton [which is where Fleming went himself]. He’s a Scottish public schoolboy, and I wanted to reclaim him for the hameland.’

There’s another overlap with the Bond of Solo and Boyd’s seedcorn 17th year: 1969 was the year Boyd first lived in London, in the summer holidays after finishing the lower sixth at Gordonstoun. This was, admittedly, in a down-at-heel part of Pimlico, rather than Chelsea, where Fleming’s mother lived and where Fleming insisted that Bond himself lived in a ‘book-lined’ flat in Wellington Square, less than a quarter of a mile away from Boyd’s own house.

And 1969 is, too, the year in which Solo is set, with a 45-year-old Bond – old enough to have served at the end of the Second World War – now strolling down the King’s Road, looking at the mini-skirted girls and wondering what the world is coming to (although really not minding one bit). The 17-year-old Boyd presumably didn’t mind too much either.

Really, of course, there’s far more to Boyd’s Solo than my simplistic thesis about the overlaps between a fictional hero’s life and a real-life author’s teenage years would suggest. In actual fact, Boyd’s pathway to writing about Bond is just as much through his interest in Fleming. In Any Human Heart, it is Fleming, then working in naval intelligence, who recruits Logan Mountstuart as a naval attaché with a mission to keep a close eye on the Duke of Windsor.

And as Boyd writes in Bamboo (2005), his excellent collection of essays, what had fascinated him about Fleming was the prospect of a man who, thanks to the success of the Bond books, had everything in the material world that any writer could possibly want but who was so unhappy that he described himself as ‘being in a hurry to get to the grave’.

In the war years, the spy years – Fleming’s own seedcorn years if Boyd’s theory holds true – it was different. Then, Fleming felt his life had a purpose. Only later did disillusion set in.

Just before I leave, Boyd tells me one last thing about 1969. It wasn’t just the summer of the moon landing, it was also the first time that he ever went to France. He and his wife Susan love the place and since 1991 have had a house in the Dordogne (with accompanying vineyard producing 7,000 bottles a year of fruity Cabernet Sauvignon, Côtes de Bergerac appelation d’origine contrôlée).

But in that first 1969 visit Boyd stayed at a roomy flat in Paris that belonged to the parent of a mutual friend. Who else was staying there? Only Martin Amis, three years older, already at Oxford. And whose father had, the previous year, written Colonel Sun, the first Ian Fleming continuation novel.

You couldn’t make it up. Or rather, according to my William Boyd theory, if it’s in your own writerly seedcorn years, you probably could.

Click HERE to read Scottish Field’s top 10 James Bond facts.

- This feature was originally published in 2014.

TAGS