16th century Scots ‘rappers’ had verbal jousts at the flyte club

What do hip-hop music and sixteenth century Scotland have in common? Not much, you’d assume.

But hip-hop – which developed in the The Bronx, New York in the 1970s – actually has its roots in the court of James IV and the Scottish art of flyting.

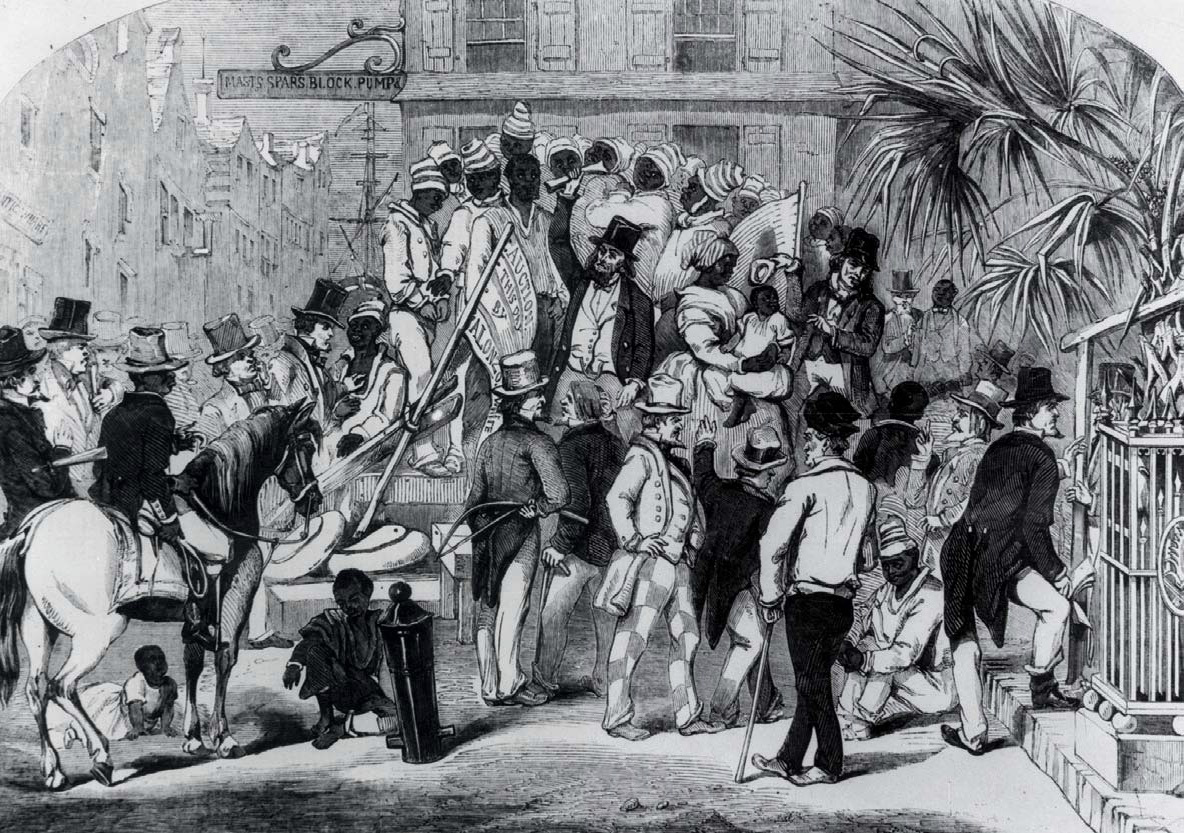

‘Flyting’ is an old Scots word meaning ‘quarreling’ or ‘contention’, and referred to poetic competitions between the 15th and 17th centuries between Scottish poets, or makars. These lyrical jousts, which took place in public arenas in front of a crowd, involved each poet taking its origins in the 1970s. The American linguist, William Labov, observed young, black American adolescents ‘playing the dozens’, or ‘sounding’ – taunting each other in the strongest terms about their personal hygiene, sexual prowess, and mothers – a game that originates from the African slave trade, when old, deformed or injured slaves were grouped together in a ‘cheap dozen’ sale to slave owners. To be sold like this was the ultimate humiliation.

However, the similarities between the rap battle and flyting are much stronger and, like the ‘dozens’, linked by the slave trade. Flyting was practised by the Scottish nobility, as well as gentlemen further down the social order – it was these men who emigrated to the Caribbean and America between the 16th and 18th centuries and became plantation, and slave, owners.

In 2008, an American academic, Professor Ferenc Szasz uncovered evidence that Scottish slave owners taught flyting to their African slaves and this is backed up by another American professor, Willie Ruff of Yale University.

The similarities between flyting and rap battling are striking. For a start, in both two people engage in a verbal duel in a public

space, the winner being the one with the best put-downs. The crowd response is also crucial to both: the last line of Dunbar and Kennedy’s flyting states, ‘juge ye now heir quha gat the war’ [You be the judge of who won the war].

‘The Dozens’ were humiliating auctions of useless slaves which were thought to have spawned rap battles

The type of put-downs contained in flyting are almost identical to those made by rappers in a freestyle battle. In The Flyting of Dumbar and Kennedie a lot is made of the east/west division between Dunbar (from East Lothian) and Kennedy (from Ayrshire). Dunbar mocks Kennedy’s western roots with the lines, ‘Thy trechour tung hes tane ane heland strynd / Ane lawland ers wald mak a bettir noyis’ [Your treacherous tongue has assumed a Highland manner / A Lowland arse could make a better noise].

The east and west coast rivalry amongst rappers is infamous, culminating in the murders of Tupac Shakur (west coast) and The Notorious B.I.G. (east coast) In The Flyting Betwixt Montgomerie and Polwart, printed in 1621, Ayrshire nobleman Alexander Montgomerie, makar to the court of James VI, puts down Sir Patrick Hume of Polwarth, from The Merse in the Borders, with these lines: ‘Foule mismade mytting, born in the Merse / Leave off thy flytting, come kisse my erse’. The verse requires no translation, except for the word ‘mytting’, which means dwarf.

Another put-down in a rap battle involves sexual jibes about your opponent, which also happens in flyting. Kennedy calls Dunbar a ‘Haltane harlot’ and Dunbar responds that Kennedy is a ‘glengoir loun’ [syphilitic ruffian], and ‘Lene larbar, loungeour, baith lowsy in lisk and lonye’ [a lean, impotent layabout, louseridden in loin and groin].

While rap lyrics are festooned with choice language, the profanity contained in the flytings printed between the 16th and 18th centuries is even more shocking. The Flyting of Dumbar and Kennedie was once famously described as ‘500 lines of filth’, while Sir Walter Scott called it ‘the most repellent poem known to me in any language’. The poem not only contains one of the oldest printed references to the ‘s’ word when Kennedy calls Dunbar a ‘schit but wit’, but also one of the earliest references to the ‘f’ and ‘c’ words – an alphabet soup of profanity that would make even rappers wince.

Rapper Eminem (right) in the film 8 Mile

Rap and flyting lyrics are intended to be witty, clever and, above all, amusing, with the humour in both immature and scatological.

Some flytings insults are very funny, such as when Dunbar tells Kennedy, ‘Thy bawis hingis throw thy breik’ [Your testicles hang through your breeches] and ‘Thy gane it garris us think that we mon de / I conjure thee, thow hungert heland gaist’ [Your face reminds us that we must die / I summon you, you hungry Highland ghost], or when he calls Kennedy a ‘Herretyk, lunatyk, purspyk, carlingis pet’ [Heretic, lunatic, pick-pocket, old woman’s fart].

Kennedy gave as good as he got, calling Dunbar a ‘dirtfast dearch’ [besmirched dwarf], the ‘Generit betwixt ane scho beir and a deill’ [the spawn of a she-bear and a devil] and a ‘crabbit, scabbit, evil facit messan tyke’ [A crabby, scabby, ugly lapdog], telling Dunbar that ‘Thy dok of dirt dreipis and will nevir dry’ [Your arse drips with excrement and will never dry].

The greatest exponents of rap have combined sophisticated wordplay with complex rhythms (and the odd expletive or two) to make them the most successful artists of the modern age.

The same is true of 16th century flyters: William Dunbar was the Eminem of his day, and a sign of his popularity is the fact that The Flyting of Dumbar and Kennedie was one of the tracts in Scotland’s first printed book, in 1508.

So before you diss and dismiss hip-hop as a vulgar art from the streets of modern America, don’t forget it began in the Jacobean courts of Scotland, and take comfort in the thought that somewhere right now, William Dunbar could be flyting, or freestyling, with 50 Cent or Eminem.

TAGS