A First World War tragedy off the coast of Scotland

A First World War naval ‘battle’ off the coast of Scotland on a wintery night in 1918 involved no enemy contact yet resulted in the tragic deaths of 270 British submariners.

It was a sea ‘battle’ that claimed 270 British submariners but which until recently remained shrouded in secrecy.

As well as a loss of life on an epic scale, this tale involves a jinxed class of submarine, one of the most farcically botched naval operations of World War I, a court martial and an official cover-up which lasted for three quarters of a century.

To make matters worse, the ‘Battle of the Isle of May’ – an incident which lasted for just over an hour but which saw five collisions involving eight different vessels, with two submarines lost, three damaged and a light cruiser disabled – didn’t even involve any enemy ships. No wonder the incident was never widely publicised and all information about it ruthlessly suppressed by the Admiralty.

The calamity happened on the night of 31 January 1918, when Admiral Beatty’s Grand British Fleet was due to rendezvous in the North Sea with a 40-vessel contingent from Rosyth that included four battleships, 14 light cruisers, several destroyers and nine K-Class submarines before heading to a full-scale exercise at Scapa Flow in Orkney.

With hindsight, perhaps the involvement of the K-class subs jinxed Operation EC1. Even before then the K-class submarines had earned the unfortunate nickname of ‘Kalamity-class’ within the Royal Navy because, of the 18 built in 1917, none of these unwieldy vessels were lost in action but six were sunk in accidents, with two perishing on the fateful night in the Firth of Forth and another disappearing with all hands off Milford Haven in 1921 having collided with a destroyer.

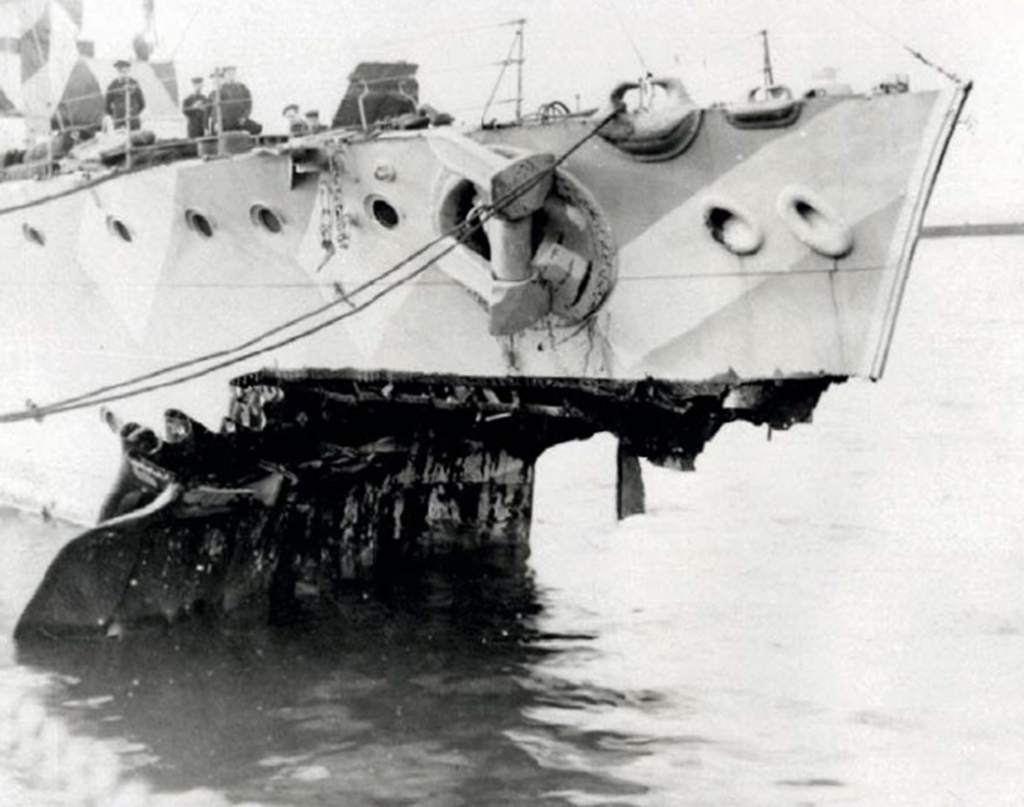

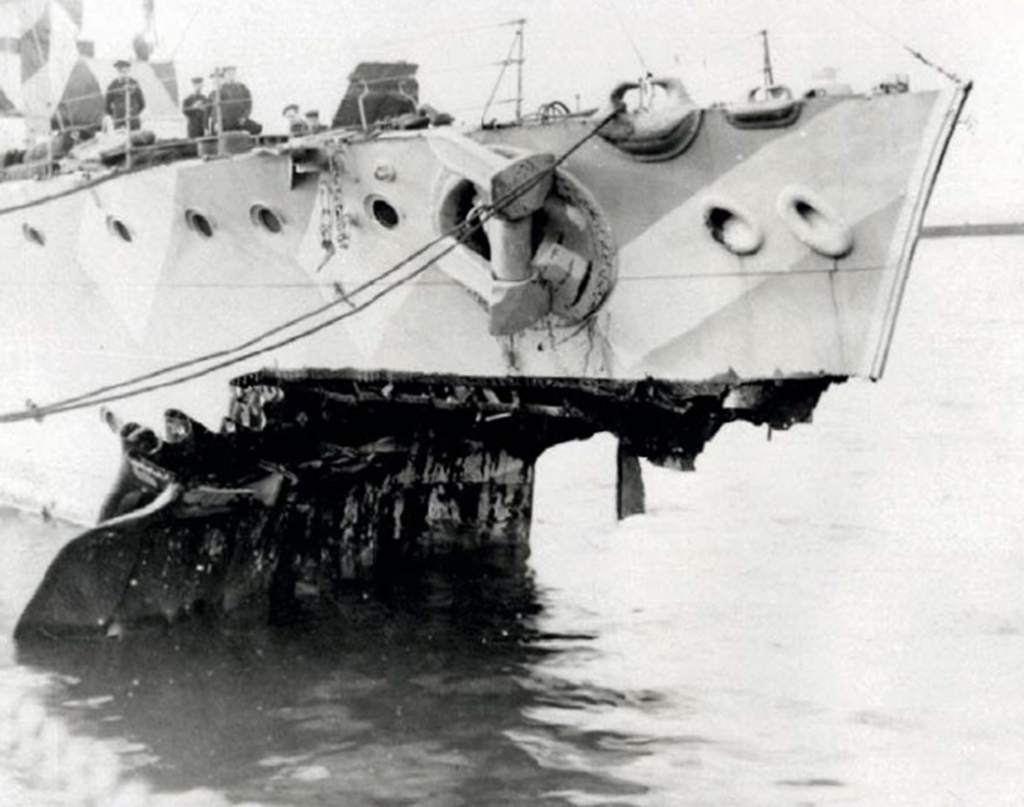

The torn bow of the K17, sunk after HMS Fearless smashed into her in the dark

The reason for the K-class’s serial misfortunes had a direct bearing on the events of that winter’s night in 1918. The submarine was designed in response to a demand from the Admiralty for submarines that could keep pace with the Grand Fleet’s 30 battleships, which could travel at 24 knots, and ten battlecruisers which were even faster, at 28 knots.

So the K-class subs were designed to cruise on the surface at 24 knots. But to produce such speeds, they were fi tted with huge oil-fired steam turbines, which made them very large – at 338ft they were almost twice as big as the German U-boats of the time. Ungainly and hard to handle, they were slow to dive, with their German equivalents submerging five times quicker than the K-class boats. Not only did the steam engines make the submarines unbearably hot, the complicated mechanics meant they often broke down.

On the afternoon of 31 January a line of 40 ships stretching for almost 30 miles sailed out of Rosyth. The entire force was led out by HMS Courageous, followed by Captain Charles Little in HMS Fearless, which led the 12th fl otilla of K-class submarines (K11, K17, K14, K12, K22), while further back was Captain Ernest Leir in the destroyer HMS Ithuriel, which led the 13th flotilla of K-class subs (K4, K3, K6, K7), followed by the battleships.

On a cold, clear winter’s night with flat calm seas, the submarines sailed 400 yards apart.

Their fear of U-boat attacks meant that the subs had half-strength navigation lights, which the blackout shields prevented following vessels from seeing if they were more than one degree off course. All initially went well, with HMS Courageous passing through the Black Rock Gate in the six-mile-wide submarine boom between Leith and Burntisland at 6.30 that evening, cruising along at 16 knots. Yet the U-boats weren’t the only ones who weren’t aware of the fleet making its way down the Firth of Forth. Twenty miles away, eight armed trawlers were sweeping for mines yet, incredibly, no-one had told them that the fleet would be passing.

Just after the Black Rock Gate, the fleet ran into some low-lying mist, which was to prove fatal. Despite the fact that the Ithuriel had lost visual contact with HMS Courageous, its skipper increased speed to 19 knots as the fleet passed through the Fidra Gap, the gate in the estuary’s outer defence boom, which stretched fifteen miles between Fidra Island, near North Berwick, and Elie Ness. K11, K17 and K14 were following the Ithuriel when, as they passed the Isle of May, the silhouettes of two minesweepers came out of the mist, veering in front of K14 and causing skipper Thomas Harbottle to change course suddenly.

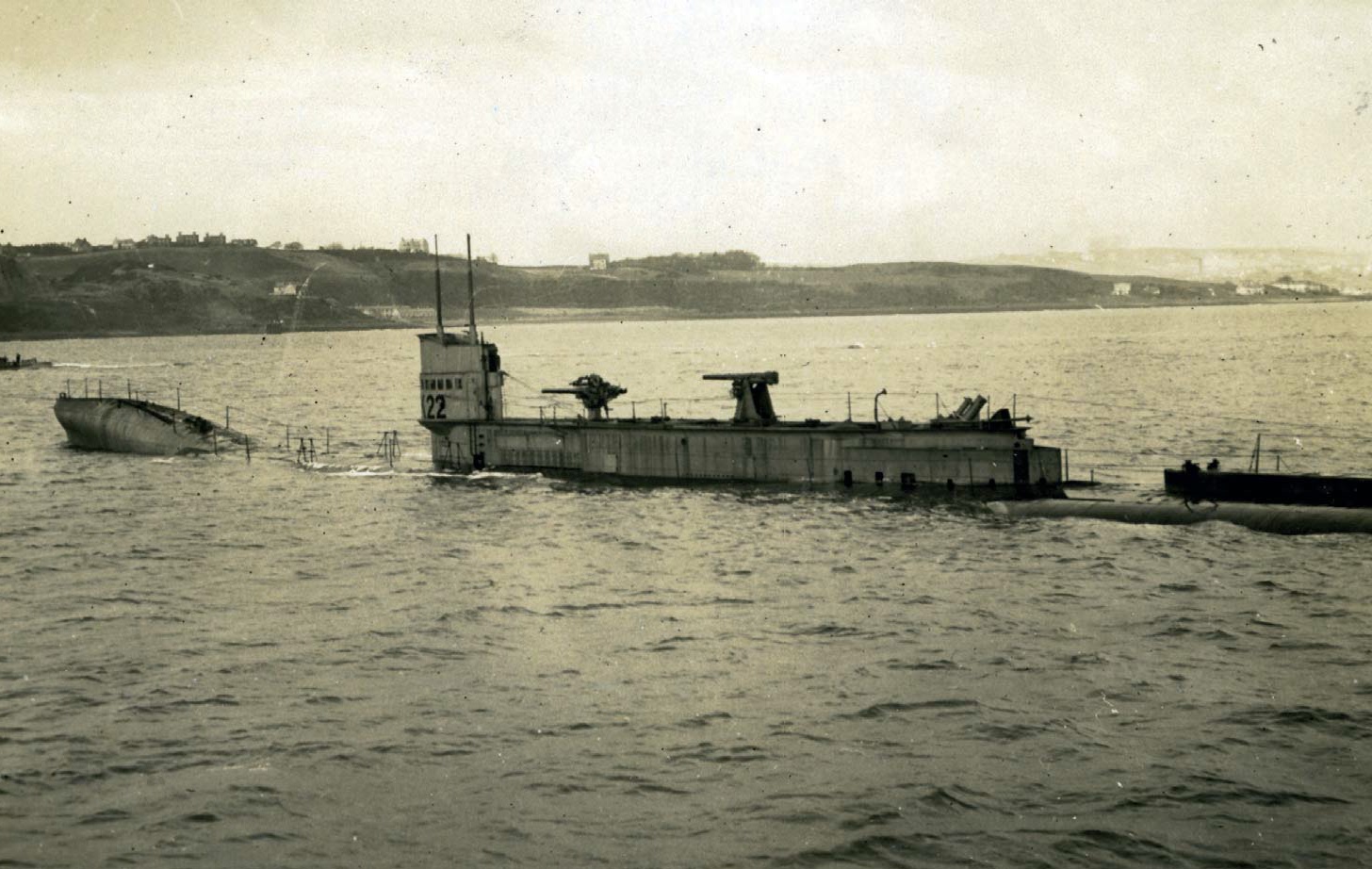

K22 underway in the Firth of Forth

The K-class subs were not made for rapid movement, however, and although K14 avoided the minesweepers, her helm jammed. Panicking, Harbottle was relieved when the next boat, K12, passed just behind him, only for K14 to be rammed by the unsuspecting K22, which was going at 19 knots and sliced through the port side of the crew space, immediately behind the bow torpedo compartment, severing part of the bows and drowning two of the crew.

The two submarines were now extremely vulnerable, with K22 partially flooded and K14 unable to move and liable to sink at any moment. The subs signalled desperately on their radios and with Aldis lamps, stationing men on the bridges with flare guns to warn other ships. Yet it was to no avail: 25 minutes after the initial collision, HMS Inflexible ploughed into the stricken K22, ripping through its bow as if it was tinfoil but making so little impact upon the battlecruiser that it simply kept going. Somehow K22, though rocking wildly, was still afloat.

Now firing off red flares every sixty seconds, the frantic radio messages sent by the two subs were finally picked up by Commander Leir on HMS Ithuriel, and at 8.10 he turned around to go to the subs’ rescue, yet unnacountably still failed to tell the rest of the fleet and almost crashed into the oncoming HMAS Australia.

The three subs following him also had to turn around, and it was only a miracle that as the Ithuriel weaved between the oncoming battleships, that none of the three less manoeuvrable subs did not run into one of the succession of ships. With the Ithuriel having failed to inform any of the other boats of their change of course they were totally on their own.

Admiral David Beatty, on the left of this photo, was in charge of the ill-fated Operation EC1 – he is pictured here with King George V and his son the Prince of Wales visiting the Grand Fleet in 1918

Leir’s oversight was to prove costly. HMS Fearless, which was leading the second group of K-class subs, smashed into K17, the third submarine following Ithuriel, her bow ripping open a hole so big that within eight minutes – just enough time for all its men to get out and into the water – the submarine had sunk.

Ithuriel sailed serenely on, unaware of the carnage in her wake, but behind her the submarines were in chaos, with one painfully near miss following another. It couldn’t last, and it didn’t, with K6 ramming into K4 just a few yards from the spot where K17 had gone down, the two submarines colliding with such violence that for 30 agonising seconds it looked as if the intertwined sister boats would go down together. At the last minute, however, K6’s powerful propellers managed to break the deadly embrace; K4 wasn’t so lucky, though, going straight to the bottom with 56 men and no survivors.

More was to come. The final three battleships, led by HMS Barham, were unaware of any crash as Ithuriel still hadn’t radioed, and all narrowly missed the bows of K3. Nor did they know that Fearless and K7 were picking up the survivors of K17, and in three terrible minutes the three ships ran down, cut to pieces and washed away most of the men from K17. Their wash even knocked several men from K7 overboard.

Although a court martial was held three days later, with five K-boat officers blamed for the collisions and one later court-martialled, the whole fiasco was kept secret until the 1990s. Indeed, the only sign that the Battle of May ever happened is a memorial cairn erected in the Fife coastal village of Anstruther on 31 January 2002, on the harbour, opposite the Isle of May, a fitting tribute to one of the most bizarre naval encounters of all time.

(This feature was originally published in December 2011)

TAGS