Art treasures were sold as palace vanished from sight

The demolition of Hamilton Palace at Hamilton in South Lanarkshire in the 1920s and the dispersal of its treasures in two sales in 1882 and 1919 was a national tragedy.

It was the grandest country house in Scotland and was filled with outstanding furniture and art, thanks to Alexander, 10th Duke of Hamilton (1767-1852). The sales attracted worldwide interest; the 1882 sale raised nearly £400,000, a colossal sum at the time, and saw the 10th Duke’s prized collection scattered across the globe.

Items from Hamilton Palace have been added to National Museums Scotland’s collections over the last 40 years, some of which will be on display in one of ten new galleries of applied art, fashion, design, science and technology, which opened at the National Museum of Scotland on 8 July.

From part of a silver-gilt tea service owned by the Emperor Napoleon to a section of a drawing room wall from the palace, they illustrate the prolific collecting of an extraordinary man driven by an intense desire to demonstrate his wealth, status and power.

The Marble Hall on the first floor, showing three of the five bronze statues associated with King Francis I of France

Alexander, 10th Duke of Hamilton, was immensely proud of his family’s status. As a consequence of the marriage of the 1st Lord Hamilton to a daughter of King James II in the 15th century, the Duke’s ancestor, the 2nd Earl of Arran, was heir presumptive to the throne of Scotland and Regent of Scotland during the minority of Mary, Queen of Scots. King Charles I awarded the dukedom of Hamilton to his relatives in 1643, and both the 1st Duke and his brother, the 2nd Duke, went on to die for the Stuart cause during the Civil War. In 1711, Queen Anne granted a second dukedom, that of Brandon, to the 4th Duke of Hamilton.

Alexander was 10th Duke of Hamilton, 7th Duke of Brandon and the premier peer of Scotland. He also claimed the French dukedom of Châtelherault, which had been awarded to the 2nd Earl of Arran by King Henry II of France in 1548-49, and viewed himself as the legitimate heir to the throne of Scotland, following the death of Cardinal Henry, Duke of York, the last of the male Stuart line, in 1807.

Between 1824 and 1831, the 10th Duke built a huge, north-facing addition onto the back of the small, south-facing baroque palace, which had been constructed in the 1690s. The Duke filled the palace with furniture and art, and created the Scottish equivalent of the British Royal Collection.

Many of these items were chosen to emphasise the Duke’s own exalted status by associating him with emperors, kings and queens.

Thus, visitors to Hamilton Palace climbed a great ceremonial staircase watched by black basalt busts of emperors and ran the gauntlet past five life-size bronze copies of Classical statues, which were believed to have been made for King Francis I of France.

They then found themselves in a large room with a substantial marble bust of the Emperor Napoleon I and Italian Old Master paintings.

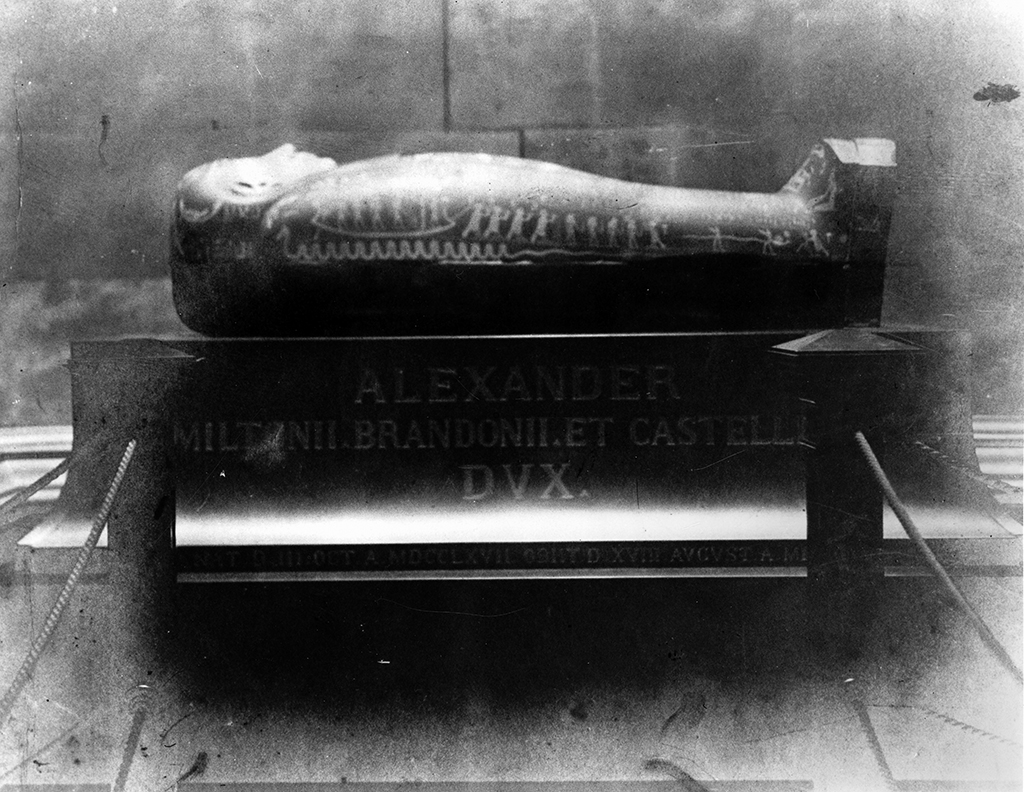

The Egyptian sarcophagus containing the 10th Duke of Hamilton

Later rooms contained dozens of examples of French 18th-century furniture, including some of British ambassador in St Petersburg, the Duke bought an exceptionally large Byzantine sardonyx bowl, in the belief that it was the holy water stoup of the Emperor Charlemagne, the founder of the Holy Roman Empire.

Back in London in 1812, he paid more than £240 for an enamelled gold stand from a gold monstrance that the Emperor Philip II of Spain had presented to the royal monastery of the Escorial, outside Madrid.

The 10th Duke united the two parts to form an astonishing imperial relic. It was the most highly valued object in his collection and an annotation in the 1852-53 palace inventory reveals that it was intended to serve as the baptismal font of the House of Hamilton.

The 10th Duke admired Napoleon as the saviour of the French Revolution and commissioned a portrait of him from his own official painter, Jacques-Louis David, in 1811. After the Emperor’s final defeat, the Duke went to live in Rome and became a close friend of Napoleon’s favourite sister, Princess Pauline Borghese.

The Hamilton Mausoleum, built by the 10th Duke of Hamilton, is all that visibly remains of the Hamilton Palace Estate

On her death in 1825, Princess Pauline bequeathed her travelling service – containing dozens of exquisite gold, silver-gilt, glass and ivory items – to the Duke. The gift inspired him to commission Napoleon’s architect Charles Percier to design interiors for Hamilton Palace and to purchase the silver-gilt ‘tea service’ which had been supplied in connection with the Emperor’s marriage to the Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria in 1810 from King Charles X of France in 1830.

These are also displayed to great effect. They reflect the character and interests of an extraordinary man, who, due to his belief in his own importance and his interest as a Freemason in ancient Egypt, would elect to be mummified and buried in an ancient Egyptian sarcophagus, inside a new mausoleum in the grounds of Hamilton Palace, in 1852 (now one of the town’s most famous buildings).

The ‘very Duke of very Dukes’ could never have imagined that his collection would be sold off and his beloved palace razed to the ground over the next 80 years.

TAGS