McIlvanney was the godfather of tartan noir

Long before Rankin or Welsh had ever picked up a pen, William McIlvanney had already created some of the most iconic hard men in Scottish literature.

The writer, who died in December 2015, casts a shadow over the literary world in Scotland even today, and his memory lives on with a prize named after him at the Bloody Scotland Awards.

Scottish Field spoke to the writer a year before his death, and turn back the clock to share his thoughts on literature and his legacy.

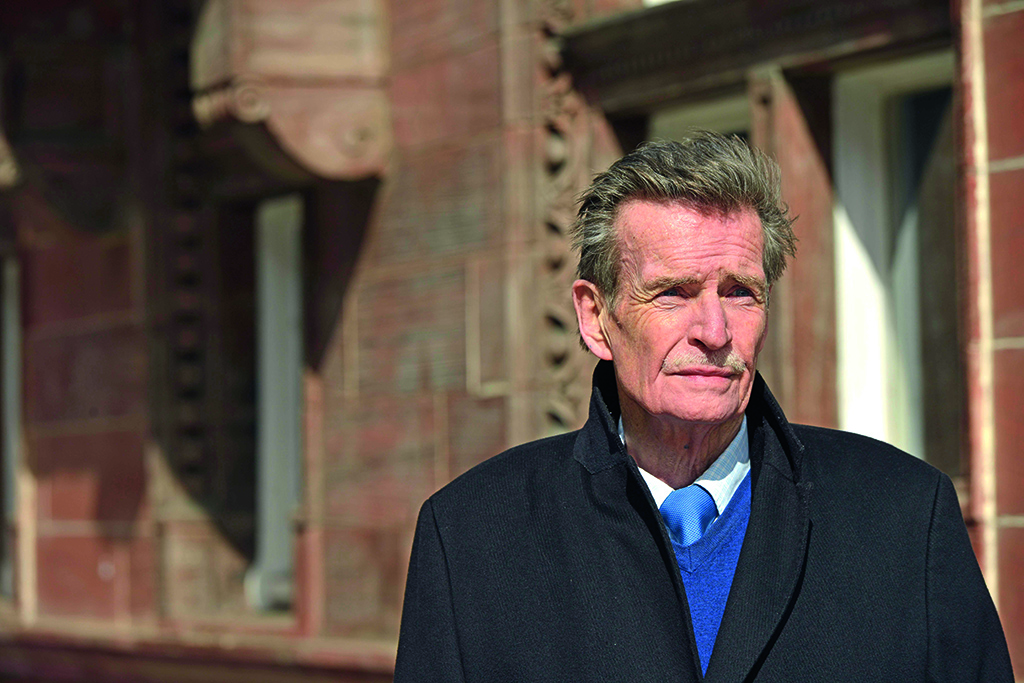

On William McIlvanney’s website (that he has such a thing is a matter of much dry amusement to this technologically illiterate author) there is a timeline of photographs of himself.

From left to right he turns from Brad Pitt, via pre-perm Kevin Keegan, to the immaculate gent sitting across the restaurant table. Now 77, Willie, as everyone calls him, still has a splendid head of hair and can work a black velvet jacket at lunch.

In his eighth decade McIlvanney is enjoying something of a renaissance. His nine novels have been reissued by Edinburgh-based publishing house Canongate. He has since been reading from them pretty much non-stop, at solo events and with the ‘tartan noir’ writers who invariably cite him as their inspiration.

He had, he claims, been vaguely aware that the likes of Christopher Brookmyre and Ian Rankin thought he was a top fella (although McIlvanney, who has an elegant vocabulary, would never utter such a vulgar phrase). But sitting beside them on a stage, with an audience full of readers, talking about their love for his work, was quite a different experience.

‘I think, when I resurrected, I was aware that a lot of crime writers had designated me the godfather,’ he says thoughtfully. ‘It was a rather bizarre feeling. When I went to Bloody Scotland [a crime-writing festival] I was astonished at the appreciation I received. My main feeling was amazement that the stuff had had the impact it had. It was a real surprise.’

William McIlvanney on the street of Glasgow.

There have been other surprises. What he calls the ‘resurrection’ – the reissue of his back catalogue – was literary agent Jenny Brown’s idea. She approached him and said she would like to represent him (he’d binned his London agent and publisher), then persuaded Canongate to take the lot. McIlvanney still sounds incredulous as he relays the story. ‘It’s very easy, given the length of time I’ve been at the game, to think you’re dead in the water, that you’ve had your time. But it has been terrific. Quite a Lazarus job.’ He chuckles.

One mild disadvantage of the renewed interest in his books is that he is now too busy to write any more of them. ‘I have been doing readings forever more. Which I like doing. When you sit in a room on your todd and scribble madly, it’s quite good to confront people who may actually have read what you’ve written. But it leaves me feeling a bit like a phony: William McIlvanney posing as a writer.’

He can’t, he claims, just fit in a few paragraphs between an Ayrshire library event and a pressing literary festival. ‘I cannot write in a piecemeal way, I need a run at it.’ To finish Docherty, and the three Laidlaw books, he decamped to a cottage and got on with it.

‘It’s a kind of temporary madness for me – I get obsessed. And it’s hard to have a lonely obsession if you’re meeting folk all the time.’ He pauses.

‘That’s my theory, anyway. Maybe when I find total isolation I’ll just sit there and stare at the wall.’

When peace finally resumes, there are books queued up, starting with a return to Inspector Jack Laidlaw at the end of his career. What will have happened to him? Early retirement? A career change? Complete bafflement at newfangled modern technology? ‘I’m sure,’ McIlvanney says drily, ‘he’ll let me know in due course.’

It turns out that the troubled detective has stayed with the author while he has been creating other characters. ‘When I started making notes towards further Laidlaws,’ McIlvanney explains, ‘he was talking like a budgie immediately. Very talkative guy, Laidlaw. We will catch up with him at the end of the last century, when he would be approaching retirement and struggling to get to grips with text messages. A lot of police work now is dependent on the internet and DNA; it has been transformed.’

In fact, what jumped out at the author when he recently reread the first in the series, published in 1977, was that he had ‘written a historical novel’.

‘Things have changed so much, even in small ways. Laidlaw gets on a bus and there’s a conductor. He goes into a pub and lights a cigarette.’ A miasma of envy wafts across the table at this point; McIlvanney is an unreconstructed addict. ‘Then there are bigger ways, like the internet and so on. Laidlaw, like myself, is a troglodyte in that way.’

McIlvanney will not, he claims, be getting to grips with Google Earth and WhatsApp in the interests of research. ‘I won’t navigate it, I’ll

bypass it, as Laidlaw would.’

William McIlvanney is the godfather of Scots crime writing

Then there’s another novel that he would like to write. ‘It’s not talkable about,’ he says with a smile. ‘It will be a very, very strange book that maybe nobody will want to read but I want to write it.’ I admit to being intrigued. That smile again. Allan Massie described him as Scotland’s Kafka but he is also Scotland’s Rhett Butler.

‘Don’t be, my dear. Save your intriguedness.’

It seems that no one, not even his agent, knows about the as-yet-unwritten, very, very strange book. ‘I don’t talk to Jenny. I don’t talk to anybody. Why bore people to death with what you might do? Do it and see what happens.’

It turns out that his voting intentions for the forthcoming referendum are surprisingly similar. Despite having no faith in the factual information offered by either camp, he is voting yes. ‘There’s so much unsubstantiated rumour about it, you’ve got to close your eyes and jump. The information’s so confused, it’s all characterised by a pontifical vagueness – nobody can justify anything at all.’

He doesn’t subscribe to the theory, espoused by other yes-voting writers, that an independent Scotland would become a fecund creative hub with great scenery. ‘I don’t think that’s how creativity works. Creativity happens in spite of many things, not because you’ve got a specially nurtured environment. The best kind of creativity is a kind of defiance.

‘It’s perfectly valid that a society should encourage its writers but I don’t think that necessarily means a great efflorescence of wonderful writing. It just creates a good atmosphere to see what happens. The best writing is always a bit mysterious. Where it comes from you are not entirely sure.’

For him, the referendum is colours-to-themast time. ‘I think the Scots have been saying for years, because we’re partially disenfranchised by the size of the English vote, that we’re really more radical than we’re being allowed to be. We’ve had the means to profess more radicalism than we can realise. So let’s see. Prove it.’

Despite this fighting talk, he thinks we will be staying in the UK. ‘I think the likelihood is no. I think it’s quite a Scots thing to do, to go to

the brink and pull back.’ That is not his style, in writing or in deciding the future arrangements of the state. ‘As my old man used to say in a crisis, you’ve got to shout Geronimo and jump. There’s not much else you can do.’

- This feature was originally published in 2014.

TAGS