Bitter rivals, the Marquis of Montrose and Argyll are two of the most remarkable yet misunderstood figures in Scottish history.

Just as every good story needs a hero, so every good hero needs a villain. It is in these terms that the history of the Scottish Civil War of 1644-45, and the Scottish Revolution, the National Covenant, and the two Bishops’ Wars which all preceded it, has usually been told.

Who could be a finer romantic hero than James Graham, 1st Marquis of Montrose, the brave military genius, the gambler who risked all for an unpopular King he loved, and paid for it with his life? And if Montrose is the hero, then Archibald Campbell, Marquis of Argyll, his great rival, must be the villain. In contrast to Montrose he is a more opaque figure, cautious and calculating, a chess player not a risk taker.

There are striking parallels in the lives of Montrose and Argyll, in their backgrounds, education, military experience, political involvement, the way in which they were both betrayed by their King, and how they each faced an untimely death. Both had enormous self-belief and an unshakeable conviction in their cause. Both were devoted to their masters – Montrose to his King; Argyll to God and his Kirk. Both demonstrated courage that was at times breathtaking: Montrose on the battlefield, Argyll on the scaffold. Both died as heroes, and martyrs, to their followers.

James Graham, Marquis of Montrose, is often seen as the hero

figure,

It is fair to say Montrose usually had the better press. One historian, whilst praising Montrose as ‘a much adored and courageous leader, a poet and a patriot’, damns Argyll as ‘a most unpleasant man, cowardly, cruel, dishonourable in his dealings and entirely without compassion’. A recent BBC/Open University resource described Argyll as ‘a cynical opportunist whose overt political ambition created divisions in the Covenanter ranks and caused former colleagues to take up arms for the King’.

In a Hollywood treatment of their story, Montrose, principled, dashing and brave, would be played by the star, with the scheming, cowardly, devout Argyll making a fine part for a character actor used to portraying the black-hearted villain. But this is too simplistic. For whatever Argyll lacked as a soldier, he more than made up for as a politician. He skilfully led the Covenanting faction in their disputes with Charles I, uniting nobility, the clergy and the people in a great national crusade.

It was Argyll who was the defender of the populist cause, the peoples’ champion. In mid-17th century Scotland it was Argyll who was regarded by the populace as the real hero. And it is Argyll’s political ideas, and his championing of the power of Parliament against the unfettered rule of the King, that have better stood the test of time. It is not without justification that a recent biographer rates him as the leading British statesman of the age, second only to Oliver Cromwell.

The oft-portrayed villain of the piece, Archibald Campbell, Marquis of Argyll

In reality, both were heroes; both, at times, villains. Both were capable of courage and generosity, and equally capable of great cruelty. Both were military commanders and statesmen, although Montrose excelled as the former and Argyll as the latter. Both have left remarkable legacies and played a major role in shaping Scotland’s history.

Any history of the period needs to tell both their stories and to examine the extraordinary rivalry between them. It was in the 17th century that we settled the great questions about the future of our country: how we would be governed; whether the King, or Parliament, would be sovereign; if the people could worship God as they chose, or only as the Crown commanded; and what would be the relationship between Scotland and our southern neighbour.

It was the principles promoted by Argyll that won through, with the Glorious Revolution of 1688, a constitutional monarchy, and a Kirk ordered on Presbyterian lines. Inevitably there will be those who look at the complex politics of 17th-century Scotland and try to fi nd parallels in more recent events. The Scottish Revolution of 1637-44 was a reaction to the insensitive rule of a distant government in London imposing unwanted policies, with the Scottish people rising up in a remarkable national movement demanding change.

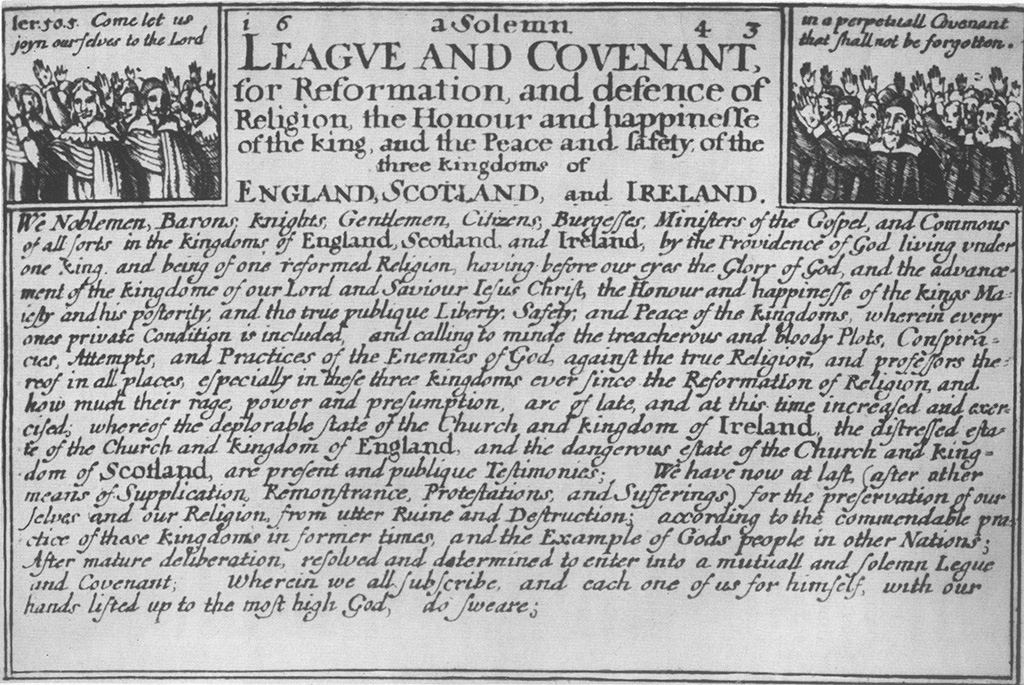

A covenant for reformation

Ambitious politicians saw the opportunity to benefit by putting themselves at the head of a popular cause. Radical parliamentary reform was delivered, but did not go far enough for some. The country found itself divided between moderates and radicals, and the divisions became ever more bitter. Those who were once allies became rivals, as the nation was torn apart in a spiral of confl ict and economic disaster.

It was a time of political and religious reform and upheaval where Montrose and Argyll were central fi gures. But their motivations were not just those of principle: they were driven by the same blend of ambition, personal loyalties, jealousies and financial necessity that politicians of all ages are prone to. It is wrong to assume that historic reforms came about because their champions were always acting altruistically; the true reasons are more complex.

They were very different in character. Where Argyll was cautious, considered, pragmatic and realistic, Montrose was principled, loyal, unbending and reckless.

Charles I

Argyll would do deals with anyone, even Montrose himself, in the wider interest. Montrose had difficulty working even with those who shared his outlook. Faced with a diffi cult choice, Argyll would take his time to weigh the options before settling on a course. Montrose was more impulsive, rushing in and acting on instinct.

Montrose’s historical contribution to Scotland is undermined by the very dash and verve which make him such an appealing romantic fi gure. He sparkles on the scene like a firework, catching all eyes for a few moments of brilliance, but then disappearing in an explosion of light. In contrast, Argyll’s role is less ostentatious but ultimately more important, deftly steering the nation through troubled times.

We neglect the study of important parts of our history. The struggles of Montrose and Argyll – Royalist and Covenanter; Cavalier and Parliamentarian; Tory and Whig – are arguably of greater signifi cance in our national story than the Jacobite risings, but it is Bonnie Prince Charlie who gets the attention.

Today, James Graham and Archibald Campbell lie in marble effigy on opposite sides of St Giles’ High Kirk in Edinburgh, with passing tourists having little inkling as to their significance. Both they, and the times they lived in, deserve to be better remembered.

(This feature was originally published in 2016)

TAGS