Did a Scot beat Darwin to his famous theory?

Did a little-known, interesting but eccentric Scot from Errol in Perthshire really beat Charles Darwin to the theory of natural selection?

Patrick Matthew — landowner, horticulturalist, silviculturalist and land improver, entrepreneur and free-trader, Chartist, author, philosopher and proponent of Scots emigration — was a man of many parts who deserves to be acknowledged and better recognised for his contributions.

Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (published in 1859) outlined his theory of natural selection, now broadly accepted as explaining the variety of flora and fauna across the natural world, how those species have evolved and how they continue to evolve.

It is one of the greatest contributions to modern scientific thinking. However there are some who suggest that Darwin first read and absorbed the writing and thoughts of Patrick Matthew.

In 1831, Matthew wrote and published a book outlining a ‘natural law of selection’ based on his work in arboriculture. Though well argued, the book was aimed at those interested in tree cultivation and faded into relative obscurity but it contained descriptions and passages explaining Matthew’s approach, honed by his expertise in establishing and improving his orchards in the Carse of Gowrie, to selecting the best trees when growing timber.

It is these descriptions that are claimed to have been incorporated into Darwin’s theory of natural selection.

As Matthew wrote: ‘There is a law universal in nature, tending to render every reproductive being the best possibly suited to its condition that its kind, or that organised matter, is susceptible of, which appears intended to model the physical and mental or instinctive powers, to their highest perfection, and to continue them so. This law sustains the lion in his strength, the hare in her swiftness, and the fox in his wiles.’

Patrick Matthew was born in 1790, at Rome Farm on Scone Estate, the son of John Matthew, a gentleman farmer, and his wife, Agnes Duncan, a relative of the famous Admiral Adam, Viscount Duncan of Camperdown.

Comfortably off, Matthew attended Edinburgh University but never graduated, leaving to take over the Duncan family lands at Gourdiehill near Errol in Perthshire inherited from his mother’s family. Following extensive travels in Europe, he then embarked on a life of estate management, entrepreneurial endeavour, writing and correspondence, all the while expressing his radical political and philosophical thoughts.

After marrying his cousin, Christian Nicol in 1817, they had eight children, of whom a number were to settle permanently overseas.

There is still extensive evidence of his influence upon the landscape; a trip along the Carse of Gowrie between Perth and Dundee, especially around the village of Errol, passes the remnants of the orchard that Matthew tended and managed (now being re-invigorated) as well as giant redwood trees, the first giant redwoods grown outside of California.

An original giant redwood planted in Scotland

Two of Matthew’s sons had travelled to California in the early 1850s during the goldrush whereupon, hearing of the discovery of the giant redwoods, they hurried to the Sierra Nevada, collected seeds and immediately dispatched them to their expert father in Perthshire.

Matthew distributed the resulting seedlings over the next few years to neighbours in the Carse and beyond. Specimens still tower above the Carse to this day, a living legacy to Matthew’s arboricultural expertise.

Matthew’s sons ultimately travelled to New Zealand, settling just north of Auckland at Matakana, acquiring land and establishing the first commercial orchard nurseries in that country. They asked their father in Scotland to source orchard material for them, using his knowledge and extensive contacts in Europe.

As a result, the area around Warkworth, Matakana and Omaha is still to this day full of orchards, vineyards and other fruit crops. So the Matthew influence remains – which is appropriate, as their father had published a

pamphlet in 1839 entitled Emigration Fields which promoted New Zealand as an ideal location for Scots to emigrate to, given the temperate nature of the land.

As a director of the Scots New Zealand Land Company, Matthew was a significant proponent of emigration for poor Scots as a means of improving their lot.

It was his experience of fruit growing and estate management that led to Matthew writing his 1831 book On Naval Timber and Arboriculture. On publication, he received some reviews but inevitably, given the ostensible subject matter, it appealed to a limited readership.

Yet while the book described Matthew’s views on growing trees, it intermingled these with comparisons with the state of man at that key period of history, with revolution across Europe and mass migration of European peoples to the various new worlds. All seemed to be in flux, and out of this Matthew fashioned his summary of a ‘natural law of selection’ in an appendix of his book, using forestry management to illustrate wider principles of man and nature in general.

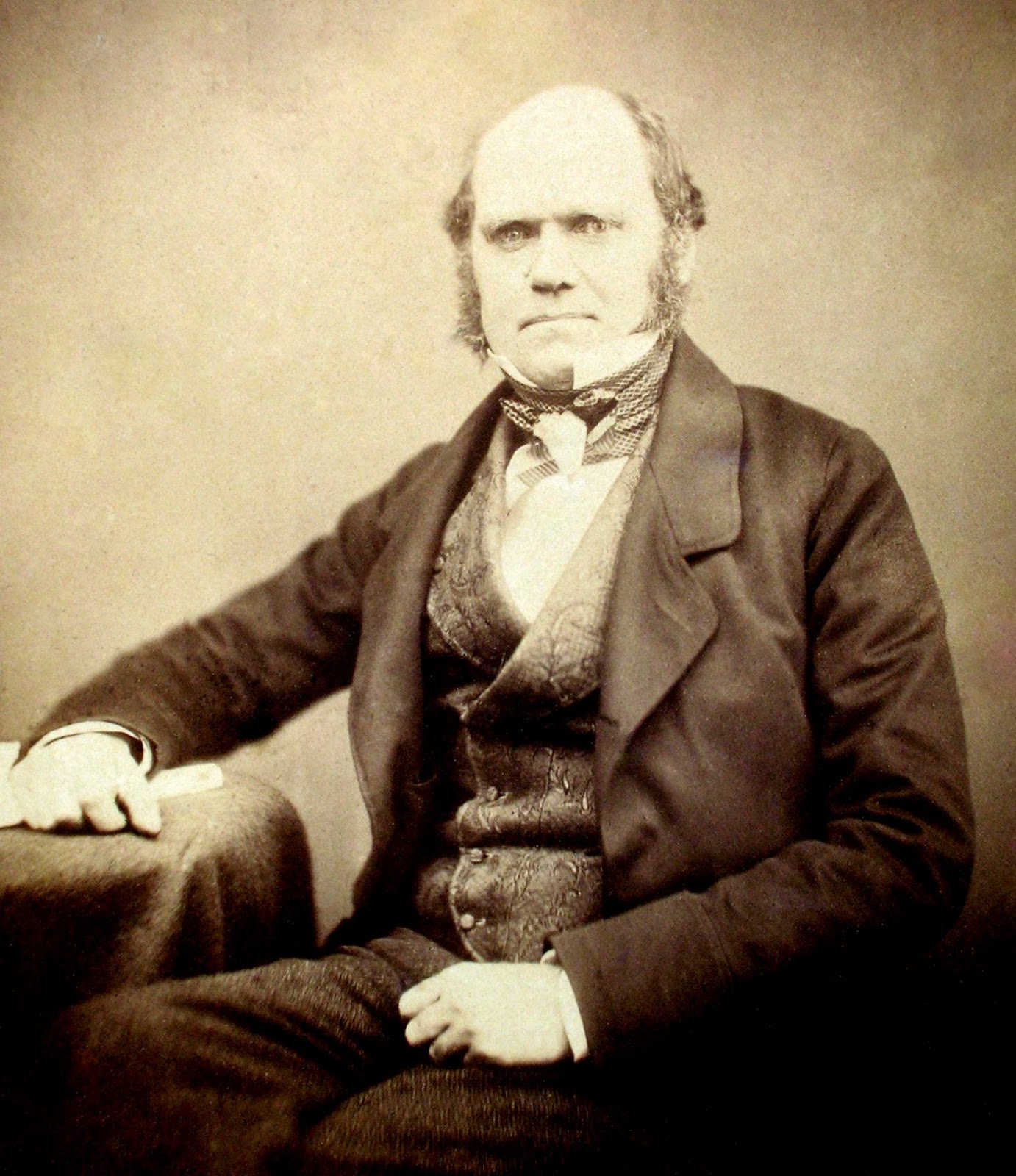

Charles Darwin

It was the use of this and other similar phrases that Matthew was later to use to challenge Darwin. After On the Origin of Species was published, Matthew wrote to the Gardener’s Chronicle in April 1860 stating that he was, in fact, the originator of the idea of natural selection and quoted extensively from his own book to

prove his point.

After some correspondence, Darwin was to acknowledge

Matthew’s earlier work — ‘I presume that I have the pleasure of addressing the… first enunciator of the theory of Natural Selection’ — but claimed that he was unaware of Matthew’s work and had arrived at his own similar conclusions independently.

Later editions of On The Origin of Species, included a ‘historical sketch’ acknowledging Matthew’s earlier work. To this day, some argue that Darwin was far more aware of Matthew’s work than he ever admitted and that Matthew’s influence on the development of the theory of natural selection is significantly under-stated.

Others vehemently maintain that Matthew was never more than a footnote.

Matthew was to continue to live a full life before his eventual death of heart failure in 1874.

Always a political radical, he was a supporter of the Chartist movement the use of force to achieve its objectives.

Nevertheless, Matthew continued to be an active contributor to political thinking, regularly corresponding with the press on all manner of topics. His trading and business interests took him to Schleswig-Holstein where he purchased an estate that his son, Alexander, took over, marrying locally and beginning a German branch of the family.

Patrick Matthew’s Gourdiehill House was demolished in 1991

He also worked to improve the lives of working people, through access to the countryside and the running of local schools.

Simultaneously, he pursued his business interests, becoming a director of the Edinburgh and Northern Railway, criticising in the press a number of aspects of the construction of the first Tay Bridge, and predicting that the bridge would fail — as it ultimately did in 1879, five years after Matthew’s death. As a result, he was dubbed locally ‘The Seer of Gourdiehill’, perhaps underplaying his more objective approach to critique and analysis.

Matthew, who once described himself as ‘a venerable, crotchety old man, with a head stuffed with old-world notions, quite unsuited to the present age of progress’, was buried in an unmarked grave in Errol churchyard.

Hugely active in his time, he has largely been forgotten about other than that footnote contribution to the theory of evolution. That is perhaps as he would have wanted it.

(This feature was originally published in 2015)

TAGS