Gregor Fisher is one of Scotland’s most iconic and beloved actors.

A Scottish national treasure, who found fame as Rab C. Nesbitt, the actor tells Scottish Field about his life.

I was brought up in a little village just outside Glasgow, called Neilston. It’s a wee place on the way to Ayrshire from Glasgow. It used to be a cotton mill town, it lies in a pretty damp valley. It’s pretty rural, pretty agricultural, pretty idyllic actually. I had a very pleasant childhood there.

I was adopted, but I didn’t know it as a child. My mother was in her fifties when she adopted me. I was three years-old and I just totally accepted that she was my mum. But when I reached about 14 years-old I started to think ‘ummm, she can’t be my mother, she’s too old.’ I wasn’t shocked when I found out. The thing is that it’s more interesting for somebody like you looking in on my life than it is for me living it.

To me, all this is my normal life, so shock never entered into it. Of course I was interested, maybe mildly surprised, but it was never traumatic. I could tell you that it was. I could call up The Sun and get it plastered on the front page saying ‘My adoption hell’, but it just wasn’t like that. I was brought up by a woman who was my mother, because, she played the part, and by god she did it well, and that was the way it was.

Until I approached journalist Melanie Reid to help me in 2014, I only knew about a quarter of my family history. We’ve written a book called The Boy from Nowhere and together we’ve discovered the other three quarters. I have two older siblings, one called Margaret, who is a retired school teacher living on the island of Tiree and my sister, Una, who is married and still lives in Neilston. I also have half brothers and sisters who I only recently met. In fact I have a whole dose of them.

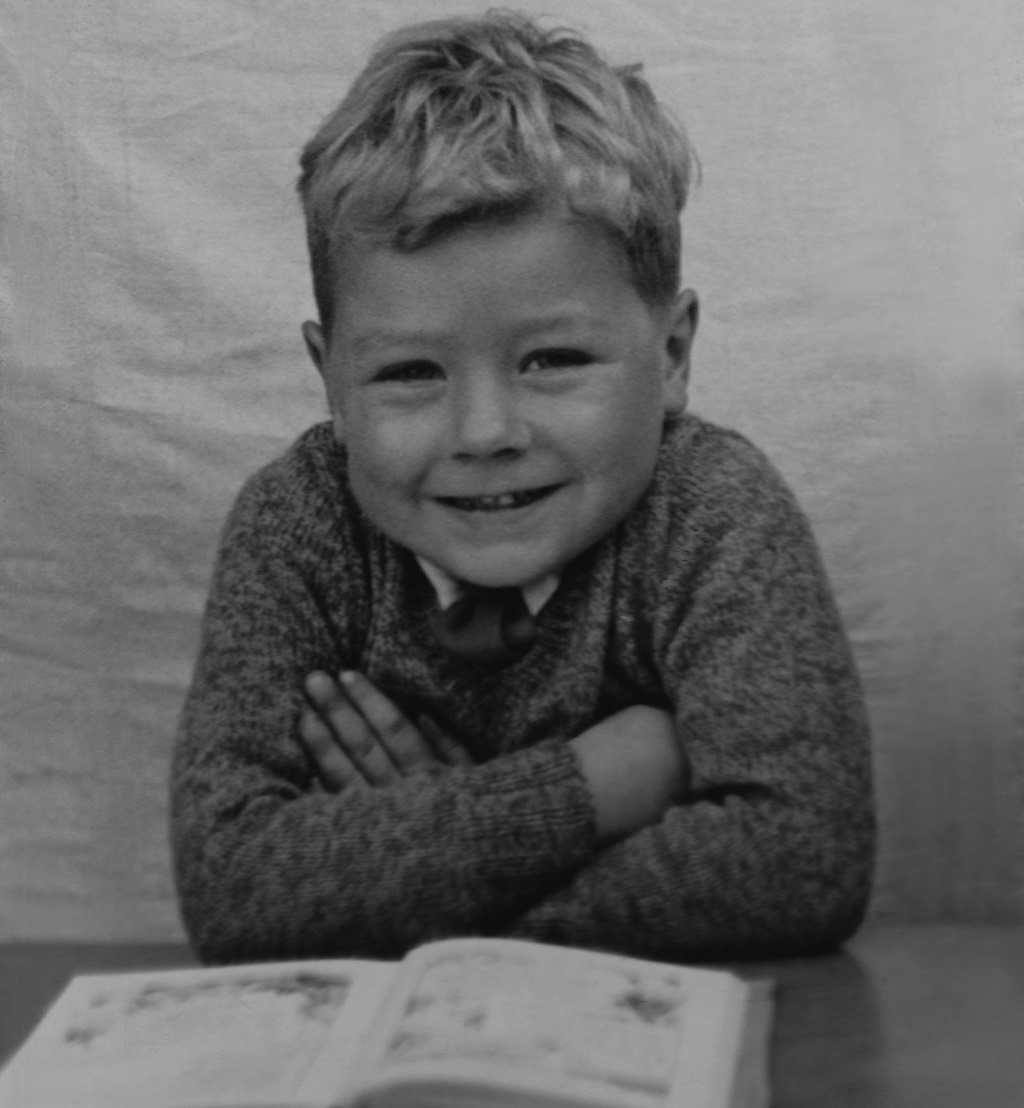

A young Gregor Fisher

School was a waste of time. Much to my regret. I don’t know if it was a combination of laziness or bad teaching but I was always the one who was staring out the window, a bit of a dreamer. I think I was a huge frustration to everybody, especially my elder sister Margaret, who was a teacher, and I think a particularly good teacher. She did try, but I think she failed miserably. I went to pretty rough schools consequently.

If you had passed your 11 plus, which I didn’t, you were given an option of some grammar school, Paisley Grammar School or something, which was a wee bit up the ladder. I went to the local secondary modern, you know where men were kitted out for the workplace. The girls were taught domestic science, to feed the drones that went to university, so no, school was a bit of a waste. I think when you’re young and daft at school you don’t think of what it’s going to be like in thirty years’ time.

They did used to do Gilbert & Sullivan operettas at school, and one particular teacher collared me in the corridor and thrust this libretto, this script or whatever you call it, and said, you’re doing this part, and I said, ‘no sir no, please don’t, I’ve done nothing, I did nothing, why me?’ But to cut a long story short, I quite liked it, I enjoyed it, it was good fun. I’m sure I wasn’t any good, I think I was bloody awful, but I did enjoy it and I suppose then I thought ‘maybe’, but I never genuinely considered that I could make a career out of it.

When I left school, I had a series of dead end jobs. I cut grass, I made sticky plaster that used to get exported out to Africa. I probably would have been sacked from most of these jobs. Going to the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Dance wasn’t something that sat well with my mother or father. They thought, get yourself a sensible job, get yourself a trade. My parents were that much older. My mother’s father had fought in the First World War. They knew what the depression was all about because they’d lived through it. They knew how uncertain life could be, so I suppose from their perspective that was good solid advice.

Gregor enjoys a cycle around Glasgow’s Botanic Gardens

I didn’t spend a great deal of time in Glasgow as a child. My mother had an aunt who lived in Shawlands, and maybe once in a blue moon we would get the bus into the city to visit her. I didn’t really get to know Glasgow until I went to the Royal Scottish Academy when I was 18 or 19-years-old. I didn’t finish the course because I was offered a job at Dundee Rep that paid £35 a week.

I didn’t really sit well at drama school. It was full of people telling me that I wasn’t speaking properly. I don’t think you can ever learn how to act properly. So, I don’t know if I really trained to become an actor. I’m still in training now, as far as I’m concerned every day’s a new day.

All the places in Glasgow that I used to go to are gone. Every time I come back to Glasgow I say ‘Where’s this? What’s that? What’s happened here?’ I was walking along Byers Road with somebody and I says: ‘What’s that?’ ‘The Chinese are building student accommodation. ‘Oh’ I said ‘right okay’. It’s not called the Royal Scottish Academy anymore, it’s called the conservatoire. Get a grip! The conservatoire of Scotland. A) that’s a French word, B) what’s that got to do with Scotland? So it’s all change nowadays.

It’s not so much favourite places that bring me back to Glasgow. Places have never been that big for me. I suppose because most of my life has been fairly transient, especially when I was a child in children’s homes and things. It’s people that matter to me. I have lots of friends, there’s one there. That’s Monica Brady. We first met at the Dundee Rep in 1976. It’s seeing familiar faces, and people you know and love in Glasgow. That’s what does it for me. It’s not ‘oh I love the view of the Kelvin’ or whatever, it’s always people. That’s what brings me back here. Not because I love looking down Buchanan Street to St Enoch’s or anything. I have an affection, there’s a familiarity to Glasgow that I like, and that’s quite cosy but that’s not the draw.

Gregor Fisher as Rab C. Nesbitt (Photo: BBC)

I shared a flat in the city with Willy Wands who is the producer of Whisky Galore, my latest film. That’s Glasgow for me, it’s these people, it’s these connections. We were all kids growing up together.

Acting is a very strange occupation for an adult human being to have. Pretending to be someone else. I’ve been doing it since I was 24, dressing up as somebody else, but when that somebody else is a woman… well, you think maybe I should’ve stuck in at school. I think I’d really like to have been a builder or an architect. One of the great passions in my life is finding old buildings and restoring them. I’ve done it in France, and I want to do another one.

I don’t get a lot of hassle in Glasgow. I think perhaps it’s to do with playing Rab C Nesbitt. I think some of his aura of slight menace makes people think ‘I’d better not, he might give me a Glasgow kiss!’ I think one of the things about that character is that he was a Glaswegian, but the great thing with Iain Pattison’s writing is that he was universal.

He exists if you walk down 42nd Street to the Bus Station in New York. He may look different, and he might be wearing an old bomber jacket, but that’s Nesbitt. It was in essence somebody who was forgotten, somebody from the so called underbelly of society. And whether it be Glasgow, Liverpool, Rome, Paris, Sydney, wherever you go you can find him. There was nothing new about Rab C. Nesbitt. The Greeks had people like Rab C. Nesbitt coming on at the interval, he’s the guy you wouldn’t want to sit next to on the bus – not that the Greek’s had buses but you know what I mean – he was the one that got away with speaking home truths about the people who ran Sparta.

I never thought of Rab C. Nesbitt as a Glasgow stereotype. I enjoyed playing him, but I don’t miss running around Glasgow in a string vest with my nipples hanging out.

I don’t think I really consider myself to be a Glaswegian. A cockney needs to be born within the sound of the Bow Bells. But then what makes a Glaswegian? Maybe I’m an adopted son of Glasgow.

This feature originally appeared in Scottish Field’s December 2016 issue.

TAGS