Frederick Douglass spoke on his abolition mission

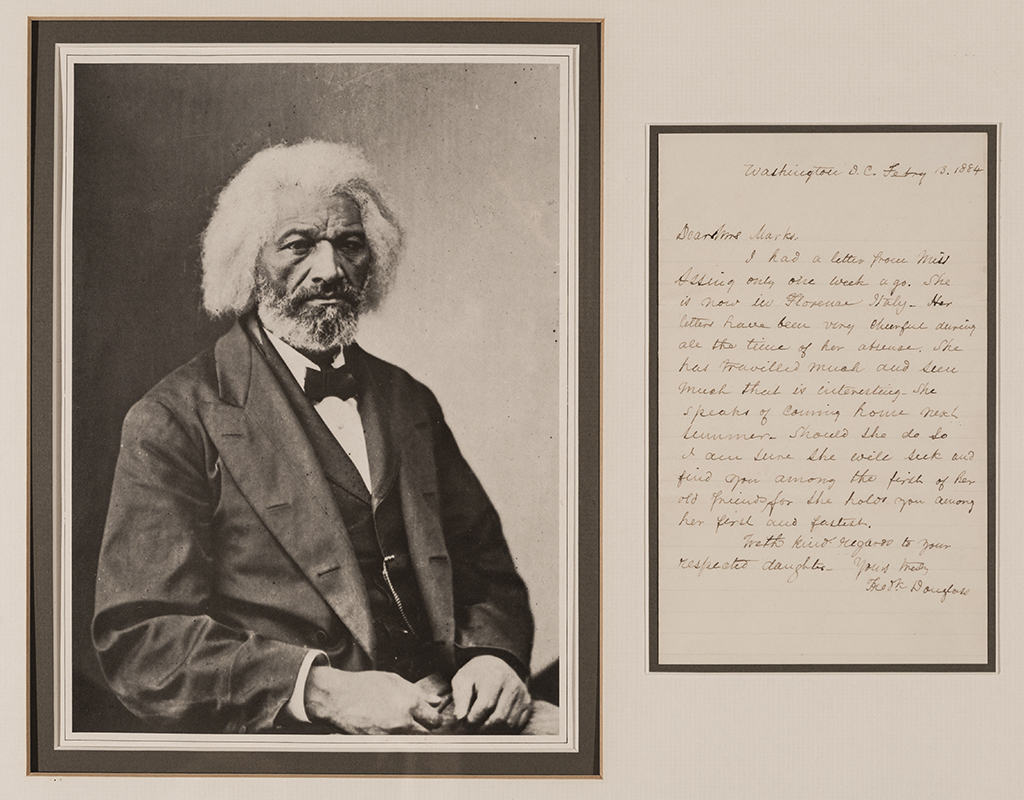

Frederick Douglass, the pioneering abolitionist, former slave, writer, and the first African American to run for high office, had a relationship with Scotland long before he ever set foot on these shores.

At a Burns Supper in 1849 when he returned to New York, he pronounced ‘though I am not a Scotchman, and have a coloured skin, I am proud to be among you this evening. And if any think me out of my place on this occasion (pointing to the picture of Burns), I beg that the blame may be laid at the door of him who taught me that “a man’s a man for a’ that”.’

At present, an exhibition on Douglass is running in Edinburgh, and will continue until next February.

To write about Frederick Douglass is to be immediately entangled in ambiguity. When was he born? He himself wrote: ‘I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it,’ with the best guess being around 1818. He chose his own birthday, celebrating it on February 14.

He also chose his own name. When he escaped from the South to New Bedford and was sheltered by one Nathan Johnson, the question of his name arose. Although he was supposedly ‘Frederick Bailey’, his host realised that, despite having assumed many pseudonyms, he needed a new moniker.

Johnson had been reading Sir Walter Scott’s The Lady Of The Lake, which features, ironically, ‘the Black Douglas’, so Frederick took the name Douglass.

In one of his autobiographies, My Bondage, the newly named Douglass wrote that his host was ‘pleased to regard me as a suitable person to wear this, one of Scotland’s many famous names. Considering the noble hospitality and manly character of Nathan Johnson, I have felt that he, better than I, illustrated the virtues of the great Scottish chief. Sure I am, that had any slave-catcher entered his domicile, with a view to molest any one of his household, he would have shown himself like him of the “stalwart hand”.’

Yet when Douglass, on a lecture tour of Britain and Ireland, arrived in Scotland the ideals of his cause and the politics of the time came into conflict. Scotland had, in some ways, a proud heritage in opposing slavery.

Joseph Knight, so vividly brought back to life in the novel of the same name by James Robertson, had pleaded his case in 1777 as the Court of Session pronounced ‘the dominion assumed over this Negro, under the law of Jamaica, being unjust, could not be supported in this country to any extent: That, therefore, the defender had no right to the Negro’s service for any space of time, nor to send him out of the country against his consent.’

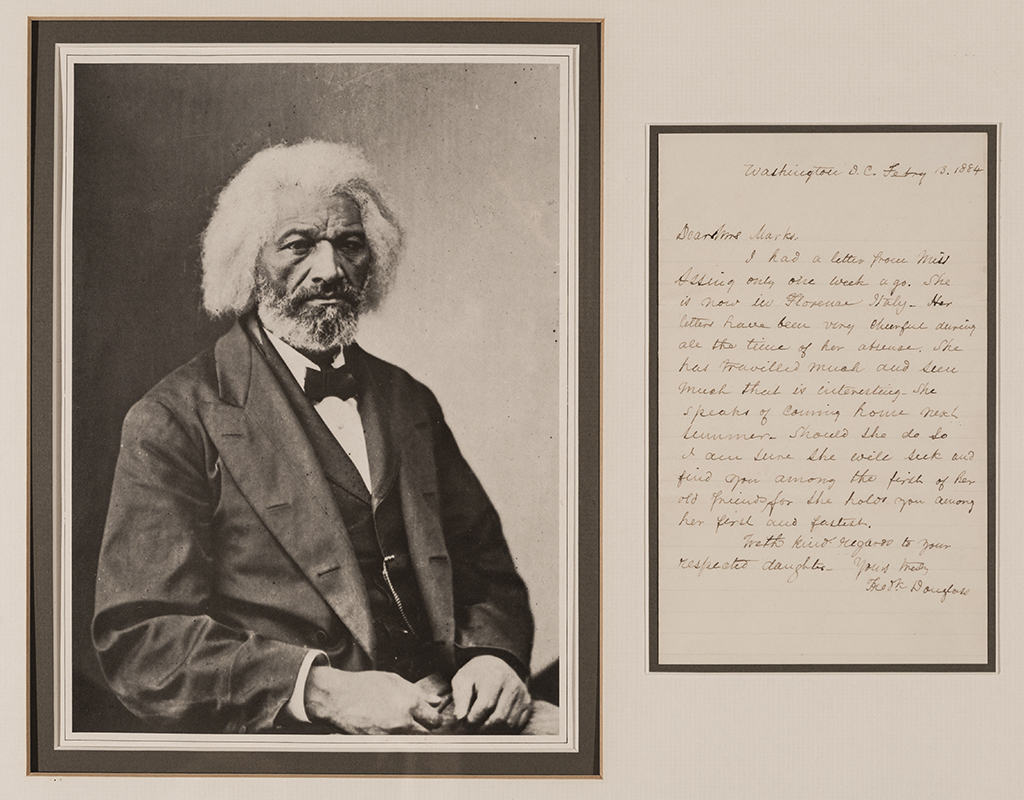

Strike for Freedom: Slavery, Civil War and the Frederick Douglass Family is currently exhibiting in Scotland (Photo: Kevin Wells)

But when Douglass arrived in 1846, one of the most liberal institutions in Scotland was embroiled in a thorny dilemma over slavery. Three years beforehand Scotland had been rocked by the Great Disruption, when nearly 500 ministers of the Church of Scotland walked out of the General Assembly and founded a new body, the Free Church of Scotland. At issue was a key democratic principle of the church which had been enshrined since Knox’s Reformation of 1560: that parishes should select their own ministers, and not have them imposed by aristocratic landlords. The ministers who walked out lost their salaries, their homes and their churches.

The new church selected as its moderator the Rev Thomas Chalmers, a mathematician, political economist, moral philosopher and inspiring orator.

Church of England bishop Samuel Wilberforce, son of the great abolitionist William Wilberforce, said of the reverend, ‘all the world is wild about Dr Chalmers’.

He had intervened in the debate about the abolition not of the slave trade but of slavery itself in a pamphlet of 1826 entitled A Few Thoughts On The Abolition Of Colonial Slavery, in which he argued that the government ought to buy one day’s freedom a week for slaves, a gradualist approach to the transition away from slavery.

But the Free Church had a major problem.

The breakaway kirk lacked buildings – not just chapels and churches, but manses and schools. In one of the most remarkable moments of populist support, the seceding church raised a fund of £400,000 – nearly £18 million in today’s money – to support the building of 700 churches, 400 manses and 500 parochial schools.

But amongst the donations, some missionaries had accepted money from slave-holding plantation owners in the American South, many of whom were emigrants from Scotland.

Douglass lectured four times in Dundee, with interest so great that the final event had to be ticketed. The Free Church was ‘in a terrible stew’ he wrote to William Lloyd Garrison, although Scotland was ‘a blaze of anti-slavery agitation’. It was, however, in Exeter that he made his most forthright denunciation of the complicity, in his address entitled A Call For The British Nation To Testify Against Slavery.

His rhetoric was impassioned. ‘When the slaves of America heard of a free church, we had reason to believe that the day of our redemption drew near [but] they accepted the slave-holders’ invitation, took their money; paralysed their own Christian feelings, turned a deaf ear to the groan of the slave as they went on their way through the South – were dumb on the question of slavery – were invited by the slave-owners to their pulpits – dined at their tables, in their pews – heard them preach to their slave congregations – took the blood money, which was offered them, and brought it to Scotland, to pay the Free Church ministers.

‘I charge them with having gone into a land of man-stealers – among men whom they knew to be man-stealers – they struck for the sake of money. Tell them to send back to America that blood stained money!’

Douglass took pains to make clear that his attack on the Free Church was not motivated from denominational rivalry, but on a matter of conscience.

When the audience in Dundee hissed, he stated that when ‘the cool voice of truth falls into the burning vortex of falsehood there would always be hissing. Innocence fears nothing. If there is a man here who feels for a moment that I should not unmask the Free Church of Scotland, he has more love for his sect than for truth, more love for his religious denomination than for God.’

The Free Church did not, as the slogan of the day went ‘SEND BACK THE MONEY’. That Douglass could still retain such affection for Scotland after such a bruising encounter with ecclesiastical realpolitik shows how ethically exemplary he was.

This feature originally appeared in 2016.

TAGS