The Jacobite defeat at the battle on Culloden Moor in 1746, ended the rebellion in Great Britain.

A rebellion that was not a war for Scottish independence, but rather to see which royal house would rule Great Britain. In 1714, the ruling Stuart family had been deposed by the House of Hanover and the Stuarts, desiring to reclaim the throne, were known as Jacobites.

Much of the Jacobites’ support was provided by the Scottish clans, particularly Western and Highland

ones. The culmination of the rebellion at Culloden resulted in significant deaths for, and then subsequent persecution of, the Jacobite clans.

A little-known facet of that persecution was to enlist as many former Jacobites as possible into British Highland regiments. This was so they could be watched over by loyal officers and be sent abroad to fight for the Crown.

Additionally, the 1747 Act of Proscription was also an attempt by the Hanoverian government to weaken the clan system of society across the Highlands. The Act banned the wearing of tartan and Highland dress, except by the army. So, if a Highlander wanted to wear a kilt in the years immediately after Culloden, he would have to join the British Army to do so.

In his book, Sons Of The Mountains, Ian McCulloch writes that in 1757 the British Secretary of War ordered two regiments to be raised in the Highlands. Almost 1,500 men were recruited from the Highlands including many men from clans that had fought for the Jacobite cause. The reason that these regiments were raised was Britain’s need for military manpower for its Seven Years’ War with France. Who better to fight, bleed, and die for King George than those troublesome former Jacobites?

And so the Highlanders quickly learned the accuracy of the old British adage: ‘If you take the King’s shilling, you pay the King’s price’.

Major General David Stewart in his book Sketches of the Character, Manners and Present State of the Highlanders of Scotland, which includes details of the military service of the Highland regiments, writes that the 77th Regiment, Montgomery’s Highlanders, were sent over to the North American colonies to battle the French and their Native American allies.

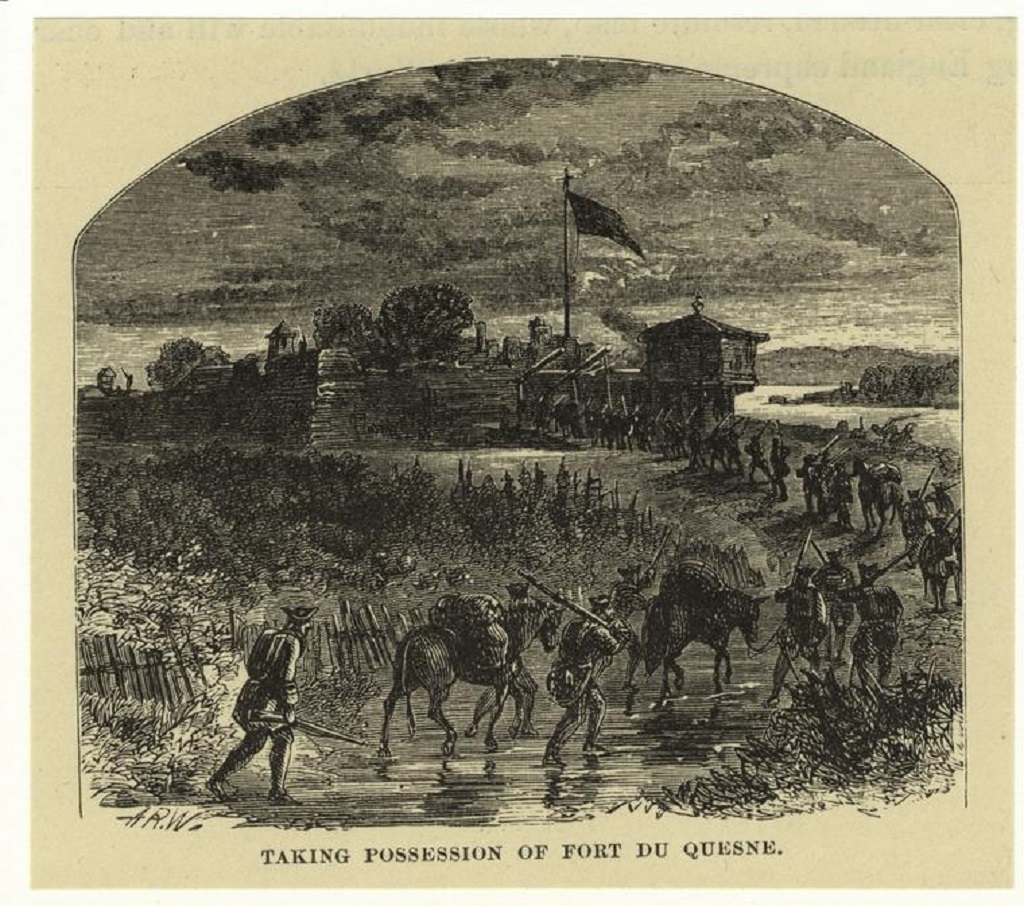

There Montgomery’s Highlanders took part in the Battle of Fort Duquesne, a British assault on the fort which was initially repulsed by the French with heavy losses in September 1758. The attack was part of a largescale

British expedition led by General John Forbes to clear the way for an invasion of Canada.

Forbes ordered Major James Grant of the 77th to reconnoiter the area with 850 men. When Grant instead decided to attack the French position, his force was out-maneuvered, surrounded, and defeated. Major Grant was taken prisoner along with many of his surviving Highland troops.

In his autobiography, Account of the remarkable occurrences in the life and travels of Colonel James Smith, the author writes that after repulsing Major Grant’s advance party, the French, knowing they were vastly outnumbered by the approaching Forbes, abandoned and burnt Fort Duquesne.

Fort Duquesne

However, before retreating from the Fort, the French made many of the Highland prisoners pay the ‘King’s price’ with brutal interest. On 25 November, the British came in sight of the smoking ruins of Fort Duquesne. No French were in sight, only a row of grisly stakes erected by their native allies. On each stake was the decapitated head of a Highlander with a kilt tied around its base.

The British went on to win the war, and thereby gained undisputed ownership of all upper North American colonies until a decade later when Britain’s original thirteen North American colonies decided to rebel against the Crown.

And just as Jacobite clans were leveraged to fill up the Highland regiments fighting the French, they would be once again tapped to return to North America to help fight the upstart colonists.

With war drums beating anew, the Highland regiments which had been disbanded were re-created. There were several regiments recruited to fight in the colonies, including many from the fertile recruiting areas of the Jacobite Highlands.

One of these regiments was the 71st (Highland) Regiment of Foot, raised by Simon Fraser and thereby known as Fraser’s Highlanders. Fraser was the son of a notorious Jacobite clan chief, and led a contingent of his clansmen out for Charles Stuart in 1745.

Following the Jacobite defeat, Fraser surrendered to the Crown and was initially imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle. Afterwards, the Crown considered him rehabilitated and he went on to serve with distinction in the British Army. As proof of his rehabilitated status, he raised significant forces which first served in the Seven Years’ War, then the American Revolution.

In 1777, the 71st was sent south to campaign in Georgia and the Carolinas. John Buchanan, in his book The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas, writes that the 71st was assigned to Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton.

In South Carolina, the 1st Battalion of Fraser’s Highlanders was effectively destroyed under Tarleton’s command at the Battle of Cowpens in January 1781. Approximately one third of British soldiers were killed or wounded with over 800 survivors captured.

Afterward, Major Arthur MacArthur of the 71st Regiment, now an American prisoner, was quoted as saying that he was an officer before Tarleton was born; and that the best troops in the King’s service were put under ‘that boy’ to be sacrificed.

Highland regiments had surely ‘paid the King’s price’ in North America during the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolution. Unfortunately, one Highland regiment was destined to have to ‘pay the piper’ one more time in North America.

During the early 1800s, Great Britain was locked in a costly war with Napoleon’s France that would only abate with Wellington’s dramatic victory at Waterloo in 1815. However, war with imperial France also had other consequences, with the background to the conflict leading to animosity between Britain and the fledgling United States that eventually resulted in the War of 1812.

These two conflicts resulted in the need for additional Highland regiments. In April 1799 the 93rd Highland Regiment was raised in Sutherland Parish near Edinburgh. The 93rd was assigned to the British command allocated to assault New Orleans, Louisiana.

The Battle of Cowpens, South Carolina, January 17, 1781

In upland South Carolina, at a place where local farmers penned their cows, an American force of 300 Continentals and 700 militia from North and South Carolina, Virginia, and Georgia, won a brillant victory against the British. On January 16, Brigadier General Daniel Morgan, pursued by 1,100 British under Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton, carefully picked his ground for a defensive battle. That night, Morgan personally went among the Continentals and militiamen to explain his plan of battle. Morgan wanted two good volleys from the militia, who would then be free to ride away. The next day, the battle went very much as Morgan had planned. Georgia and North Carolina sharpshooters, in front of the main body of American militia, picked off British cavalrymen as they rode up the slight rise toward the Americans. Then the deadly fire of the main body of South and North Carolina militia forced Tarleton to commit his reserves. Seeing the militia withdrawing as planned, the 17th Light Dragoons pursued, but were driven off by Morgan’s cavalry. Meanwhile, the British infantry, who assumed that the Americans were fleeing, were hit by the main body of Continentals, Virginia militiamen, and a company of Georgians. At the battle’s end they were aided by militia troops, who, instead of riding away as planned, attacked the 71st Highlanders, who were attempting to fight their way out of the American trap. The British lost: 100 killed including 39 officers, 229 wounded, and 600 captured. As they fled the field, Tarleton and his dragoons were pursued by Colonel William Washington’s cavalry, which included mounted Georgia and South Carolina militiamen. The Continentals who fought at Cowpens are perpetuated today by the 175th Infantry, Maryland ARNG, and the 198th Signal Battalion, Delaware ARNG, and the Virginia militia by the 116th Infantry, Virginia ARNG. The heritage of the rest of the American troops who fought i

Tragically, the forces preparing for the assault did not get the news of the impending Peace Treaty of Ghent prior to launching their attack on 8 January, 1815.

Arthur Clisby’s book, The Story of the Battle of New Orleans, states that American General Andrew Jackson made his stand five miles from New Orleans. Across his mile-long front he had built a twenty-foot-deep parapet, with a short glacis sloping down, and on it he mounted four well-protected heavy guns. Concealed behind the parapet, he had about 3,500 men.

The 93rd was ordered to advance obliquely to assist the struggling British main assault. Once there, the Brigade Commander was killed and the entire advance came to a standstill. The 93rd alone pushed out into the centre until they were only 100 yards from the American line.

Their dead Commanding Officer’s successor would neither advance nor retire without a clear order. So, there the Highlanders stood rock-like, in close order, being slowly destroyed by the concentrated fire of the American line, until the surviving British General finally withdrew them.

The Highlanders marched back with parade-ground precision, leaving three-quarters of their men killed or wounded and having laid the foundations of an immortal legend: a reputation for disciplined and indomitable courage.

Since Culloden, Jacobite descendants had been ‘Taking the King’s Shilling’. They had their heads impaled on stakes at Fort Duquesne, became casualties at Cowpens and were slaughtered by grapeshot and musket balls at New Orleans. The price asked in return for the King’s Shilling could be truly exorbitant.

The expression referenced throughout this article, ‘to take the King’s Shilling’, meant to sign up to join the British Army. This bonus payment of a shilling was offered to tempt lowly paid workers to enlist, and was successful in that aim – especially in the impoverished Highlands.

But once the shilling had been accepted, it was almost impossible to leave the army. The reason the traditional shanty The King’s Shilling included this chorus is brutally clear:

‘Come, laddies, come, hear the cannon roar. Take the king’s shilling and you’ll die in war…’

TAGS