When the euphoria that followed the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815 had subsided, Britain experienced a period of financial depression and crop failure that led to intense political unrest.

The Whig party agitated for parliamentary reform, which was resisted by the Tories, who had held power for many years and were terrified of a reaction like the French ‘reign of terror’.

Local uprisings were suppressed with vigour, such as the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester and the Battle of Bonnymuir in Scotland.

Newspapers and magazines tended to support one or other side and helped to foment the situation throughout the country – and nowhere with more intensity than in Edinburgh.

In 1817, The Scotsman was founded as a weekly newspaper with a distinctly Whig bias. A number of influential Scottish Tories felt the need to establish a Tory newspaper in opposition and financed The Beacon newspaper, which was launched in January 1821.

The Beacon proved to be a scurrilous rag, which from the outset published a series of anonymous attacks on prominent Whigs and The Scotsman.

The Scotsman maintained a dignified silence but some of the slandered Whigs instituted defamation actions against The Beacon.

James Stuart, a lawyer and landowner and a leading Whig who had been pilloried in almost every issue, took a more physical action.

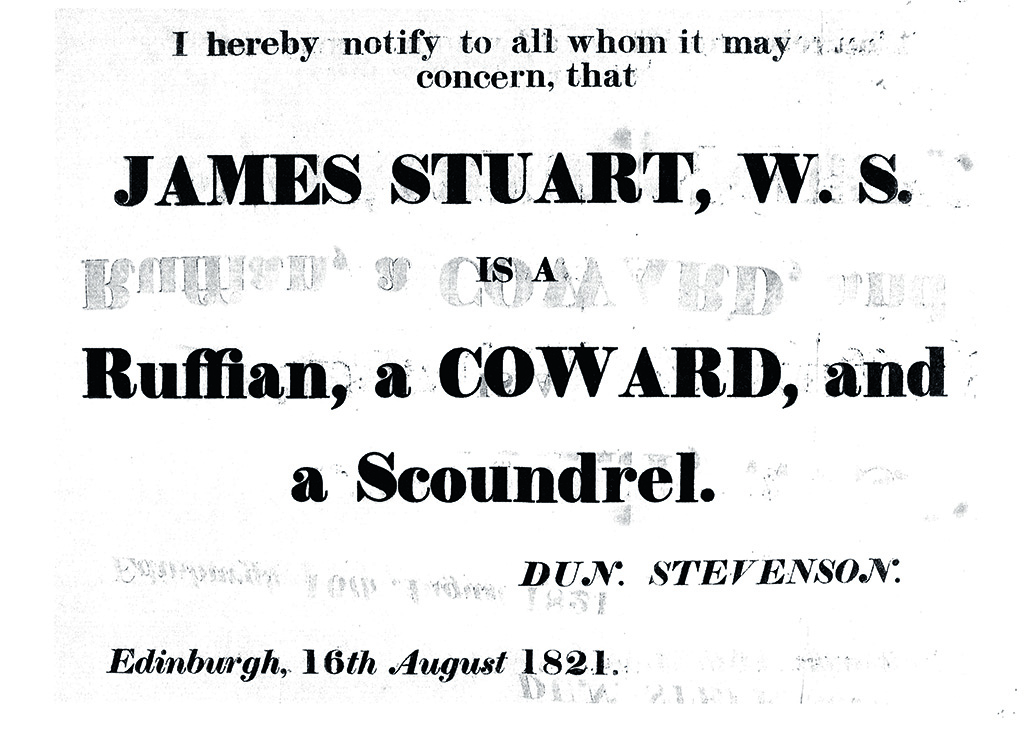

He repeatedly demanded of the publisher and printer, Duncan Stevenson, that he should divulge the names of the authors of these slanders.

Stevenson maintained the absurdity that he did not know who wrote the articles in his own paper. Stuart finally reacted by horsewhipping Stevenson in public in Parliament Square.

James Stuart

In those days, before the great fire of 1824, the square was the centre of commerce in Edinburgh, teeming with lawyers and the public, who thronged the many shops, taverns and offices that surrounded the square. This public

fracas attracted much attention and Stevenson retaliated by challenging Stuart to a duel.

The etiquette of duelling at that time was well defined; one consideration being that the participants should be of equal social status.

Stuart declined the challenge on the ground that Stevenson was of inferior rank. This exposed Stuart to accusations of cowardice, which The Beacon exploited to the full. One of the litigants who had sued The Beacon managed to discover the names of the 15 secret Tory backers of the paper, who included such well known figures as Sir Walter Scott, the Lord Advocate, the

Solicitor General and the Lord Provost of Edinburgh.

The backers, shamed by their exposure, withdrew support and The Beacon ceased publication within a year of its foundation.

Following the demise of The Beacon, a similar Tory paper, entitled The Sentinel, appeared in Glasgow – like a pheonix from the ashes. This continued without interruption the same tirade of abuse and slanders against Stuart and his kind. Stuart became incandescent. He instituted an action of damages against the two joint publishers of the paper, William Borthwick and

Robert Alexander. Borthwick, alarmed by this, withdrew from the paper and in the process fell out with his partner over the financial details.

Alexander arranged for Borthwick to be imprisoned for an outstanding debt. Borthwick let it be known to Stuart that, if he would withdraw the legal action against him and arrange his release from jail, he might be able to help him to discover the author of the libels. Stuart responded eagerly; he arranged Borthwick’s release and Borthwick, who had retained the keys to The Sentinel office, entered the building and managed to recover a quantity of documents that he delivered to Stuart.

Stuart pored over these papers and discovered to his amazement that the offending articles had been written by his distant cousin, Sir Alexander Boswell, the elder son of James Boswell, the biographer of Samuel Johnson. A duel was inevitable.

Boswell accepted the challenge on 23 March and both men appointed their ‘seconds’, who had the responsibility of managing the affair. Boswell chose his friend and distant relative, John Douglas, the brother of the Marquis of Queensberry, while Stuart chose the Earl of Rosslyn, a distinguished general in the Napoleonic Wars and a neighbouring landowner to Stuart’s estate in Fife.

The seconds agreed the duel could be delayed for a fortnight to allow the men to arrange their affairs. Various locations were discussed – the continent, or somewhere in England, perhaps Berwick-on-Tweed. Two days later, on 25 March, late in the evening, both protagonists were separately arrested by sheriff ’s officers and taken to the sheriff of Edinburgh to be bound over to keep the peace within Edinburghshire.

Someone, never identified, had let the sheriff know of the impending duel and he had taken the only action available to stop it. The two men suddenly realised that news of their arrest would spread throughout the city the following day, making it impossible to conduct a duel in privacy. The duel had to take place without delay.

Tuesday 26 March was a day of intense activity. From midnight, the protagonists had to contact their seconds to make new arrangements. The Earl of Rosslyn was at his home in Dysart in Fife and could not be reached in time so Stuart had to recruit an alternative second, his friend James Brougham. The seconds decided that the duel should be held in Fife to be outside the jurisdiction of the Edinburgh sheriff.

They selected Auchtertool, a village near Rosslyn’s home in Dysart, which would enable the elderly general to attend. Brougham left immediately to notify Rosslyn of the new arrangements. Boswell and Stuart then, in the small hours of the morning, roused two eminent surgeons to accompany them.

Both parties set off separately to South Queensferry at 5am and arrived there at about 6am. They crossed the Forth in separate vessels and made their way to Auchtertool. Stuart called at his country home on the way in order to write his will.

All, including Rosslyn, gathered at the destination by 10am. The seconds chose a suitable site in a dell hidden from public view and gave the duellists loaded pistols. Rosslyn gave the command – ready, steady, fire.

Boswell, who was an expert shot, deliberately fired in the air. Stuart, who had rarely fired a pistol, was horrifi ed to see his opponent drop to the ground. The bullet had hit Boswell on the shoulder, fracturing his collar bone and penetrating to the spine;

Boswell was paralysed below the neck. The surgeons probed the wound but were unable to find the bullet

A local blacksmith provided a door to act as a stretcher and helped all the participants in the duel carry the weighty Boswell a distance of a mile and a half to the home of Boswell’s cousin, Lord Balmuto, where Boswell died the following day. His funeral at his Ayrshire estate, Auchinleck, on 10 April was a splendid affair attended by the gentry of the county in about 30 carriages.

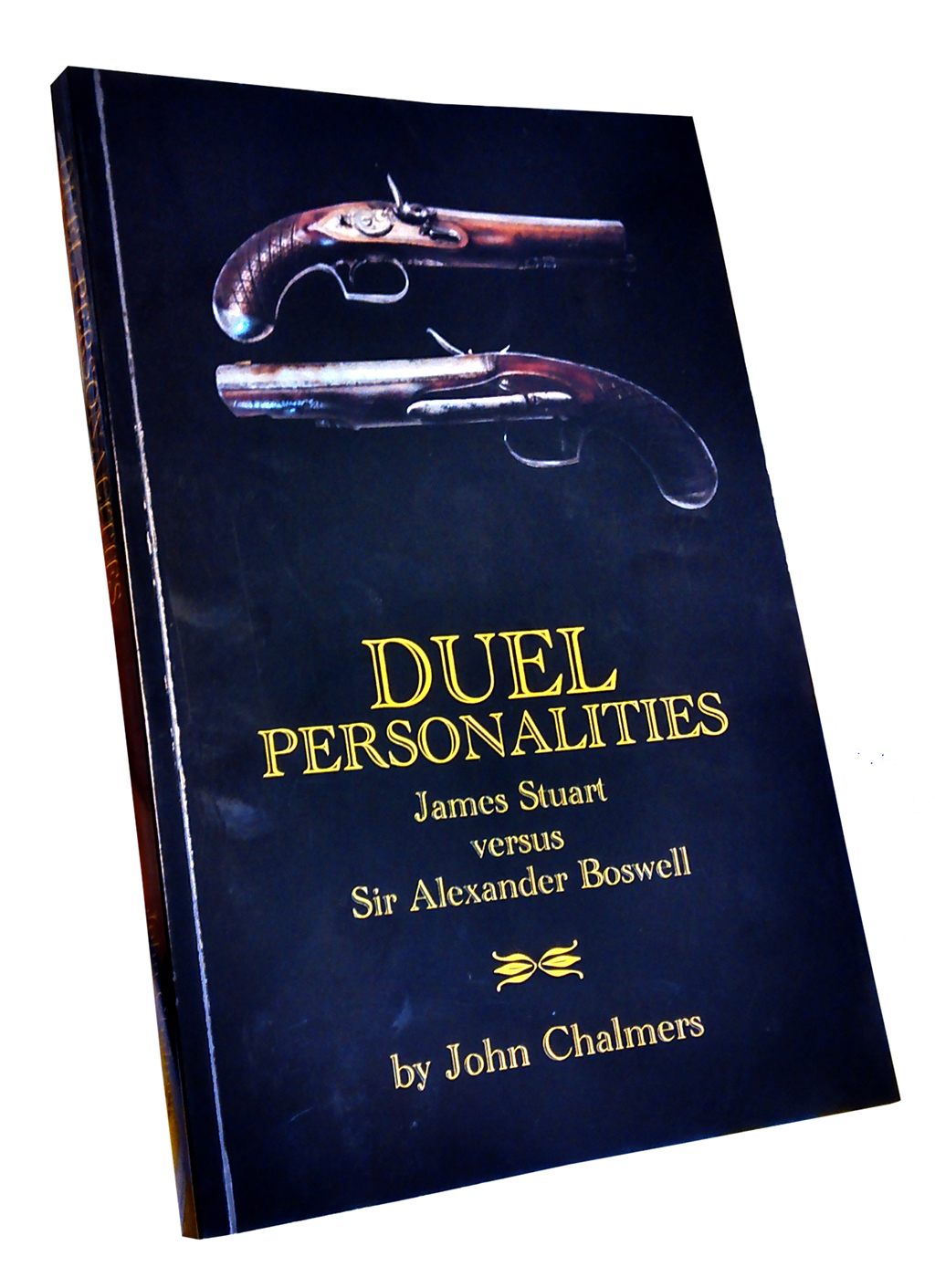

The story of the duel features in this book

Ten thousand spectators lined the route to the Boswell Mausoleum where the body was taken.

Stuart meanwhile was advised by Rosslyn to flee to France in order to avoid imprisonment pending a trial for murder. He returned for his trial on 10 June and was acquitted, which was the invariable outcome in such cases. The other consequences of the duel included the arrest and imprisonment without trial of William Borthwick on the charge of stealing documents from The Sentinel, while the Lord Advocate and his deputies were criticised in two parliamentary debates over their association with the Tory press and the handling of the trial of Stuart and the false imprisonment of Borthwick.

This was an episode with wider ramifications too: as a result of the duel between Stuart and Boswell, the Tory party suffered a setback that facilitated the passing of the 1832 Reform Act, one of the watershed moments in British history.

Stuart fared less well, ending his life as a bankrupt after investing heavily in property that crashed in the financial slump of 1825-6.

This was also the duel that effectively led to the banning of the practice, with only two more duels ever taking place in Scotland.

This feature was originally published in 2014.

TAGS