Remembering Glover San – the Scottish Samurai

Glover San, the Scottish samurai Maverick Aberdonian entrepreneur Thomas Blake Glover helped forge modern Japan yet remains little known in his homeland.

The posthumous career of Thomas Blake Glover seems to be as dynamic and full of unexpected terms as the one he enjoyed in his lifetime.

Consider what has happened in the 100 years that Glover, the buccaneering ‘Scottish Samurai’ who helped transform Japan, has been lying in the Sakamoto International Cemetery in Nagasaki.

He has been revered, forgotten, mythologised, rediscovered, praised, condemned, reappraised, apologised for, near deified and turned into grist for the Scottish political mill.

In Japan, the greatness of Fraserburgh’s most famous son – ‘GurAba San’ as he is known there – has long been taken as read.

His physical legacy is evident in Glover Gardens in Nagasaki, one of Japan’s few nineteenth century heritage sites, which attracts two million visitors a year (almost twice as many as Edinburgh Castle).

Just as tellingly, sepia photos of his whiskered face are a staple of Japanese advertising campaigns, most for Kirin Beer, produced by an industrial conglomerate that he helped to found.

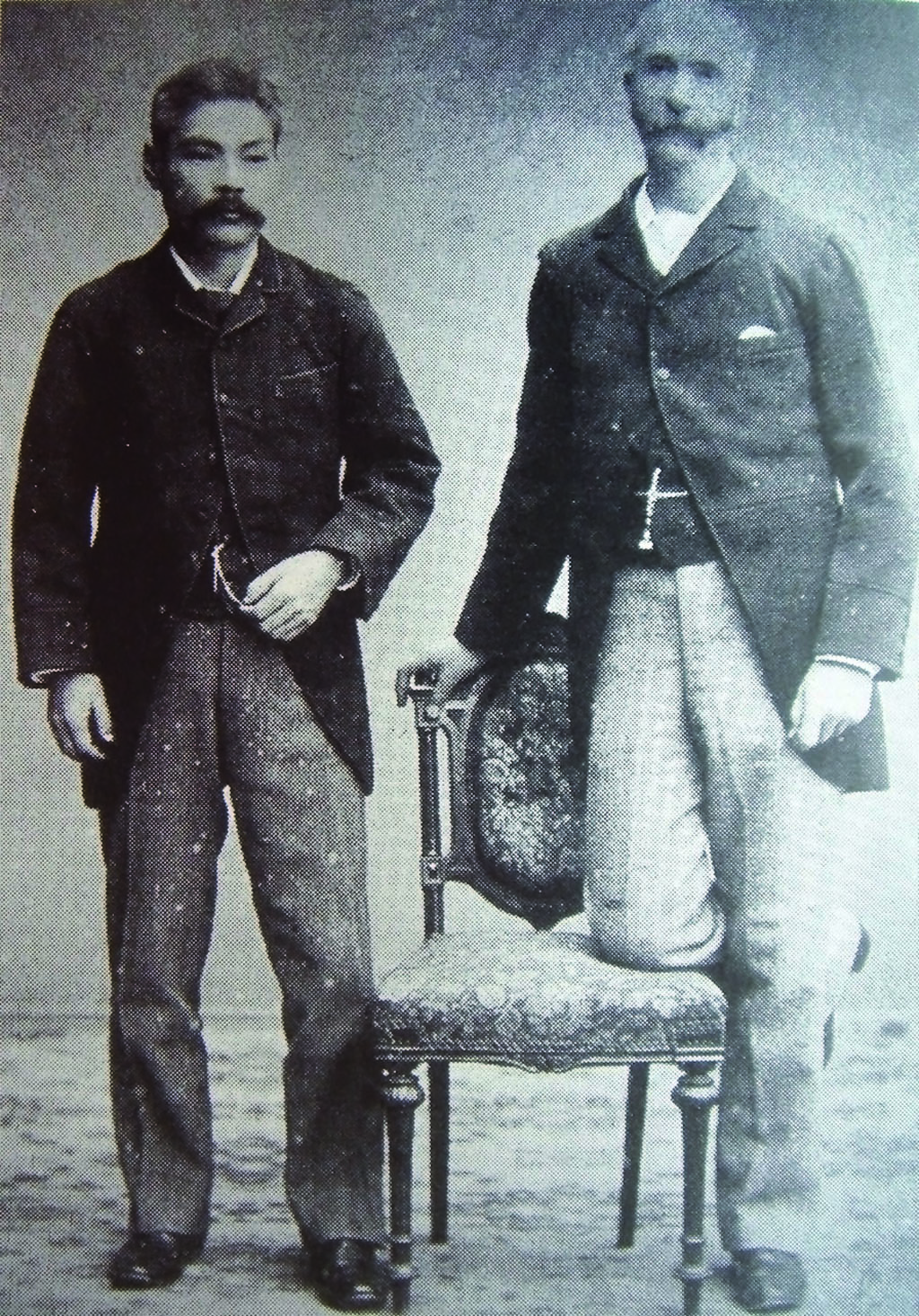

Glover with Iwasaki Yanosuke, one of Mitsubishi’s founders

Back in his homeland, Glover’s less assured second career as an icon marked a new landmark last month when he was lauded as a model of Scotland’s commercial achievements by the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Given that the otherwise comprehensive Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland doesn’t even mention Glover, the fact that former Chancellor George Osborne and his advisers had even heard of him attests to a revival, though it is a safe guess that the name was unfamiliar to most of Osborne’s dinner-jacketed audience at the CBI Scotland bash.

Those that did know more about him may have done so via a BBC Scotland documentary in Neil Oliver’s series The Last Explorers, which succinctly summarised Glover’s Japanese career as a case of ‘the right man, in the right plce, in the right time’.

Glover has spawned two biographies, plus a fictional life story by leading Scots writer Alan Spence. An aborted feature film of his life was due to have starred Sean Connery.

Born in Fraserburgh in 1838, the fifth of the harbourmaster’s eight children, the young Glover followed the well-worn path to ‘The East’ of Scottish sons of the British Empire whose prospects at home were less than exciting.

Although Shanghai, where he started as a tea (and probably opium) trader for the Scots merchant house Jardine Matheson, would have been exotic enough for a boy from Victorian Aberdeenshire, he was posted to Nagasaki, then one of the few ports through which feudal Japan allowed the contamination of foreign trade.

For an Aberdonian lad this complex, colourful, corrupt society must have seemed like another planet. Japan then was not the placid, polite country of today, but a maelstrom of feuding clans united only in their (well justified) suspicion of foreigners.

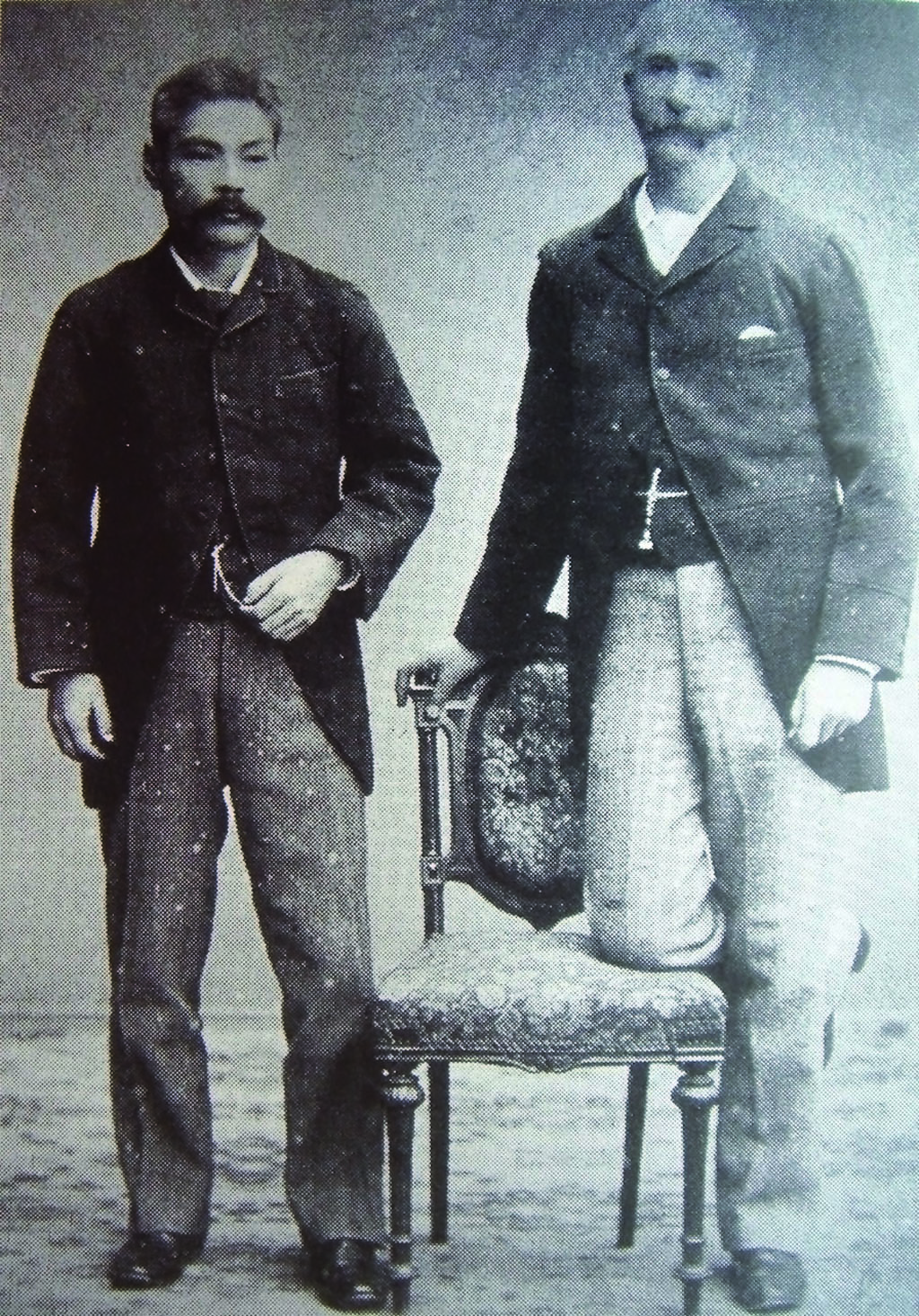

The Glover family in the early 1900s

Glover’s rapid assimilation and ascent to the top of the mercantile and social tree in theearly 1860s was a superhuman achievement, at least equal to anything he achieved afterwards in founding Japan’s business. It is symbolised by his being able to afford, within four years of arrival, Japan’s first substantial stone villa on a hill overlooking Nagasaki Bay.

It was on this cool veranda that Glover schemed, charmed, bullied and manoeuvred his way into one of the crunch points of Japanese political history, guided always by his own business interests and his ability to keep abreast of the nineteenth century’s rolling technological revolution.

Glover aligned himself with western Japan’s Satsuma and Choshu clans whose restiveness with the old regime of the Shogun in Tokyo would trigger the monarchist Meiji Revolution, Japan’s hyperspeed drive for industrialisation.

Glover’s contribution to this upheaval was twofold. He organised educational expeditions to Britain and Europe for elite samurai youths known as the ‘Choshu Five’ and the ‘Satusma eighteen’, which included trips to Glasgow, then the silicon valley of heavy engineering. More significantly, he also supplied the weaponry that would topple the dictatorial Tokugawa Shogun then recognised by Britain.

Foreign travel was forbidden to Japanese citizens by the Shogunate on pain of death, but Glover, a specialist in intrigue, helped spirit these future statesmen in and out of the country, arranging for their transport and accommodation via his Jardine Matheson networks.

A strongman amongst expatriates who thrived by playing off rival factions, Glover must have been an unreliable agent of British interests, hence the lack of official recognition. It is unlikely that Victorian morality approved of his personal life or his habit of having children with ‘temporary wives’. Modern writers have also found this less than heroic.

Nevertheless, Britain followed his lead in switching allegiance from the old regime, a diplomatic feat that ranks alongside Glover’s linguistic, entrepreneurial and technocratic ones.

The Glover Garden, a park built for Thomas Blake Glover located in Nagasaki, Japan

After the turmoil of the 1860s, Glover’s career in Japan settled into a more conventional one,in which his genius for spotting and importingkey technologies proved crucial for the emerging industrial superpower – and, of course, for this canniest of Aberdonian businessmen. He started and later managed Japan’s first coalmine on the island of Takashima, a venture that saw him go bankrupt in 1870, a temporary setback.

He supervised the building of the country’s first dry dock in Nagasaki, a venture that launched the powerful Mitsubishi conglomerate, and he founded the Japan Brewing Company, the producers of Kirin Beer. He brought in telegraph technology. He imported the first steam engine, and brokered the building of the Japanese Navy’s first three warships in Aberdeen.

The impact of these efforts resulted in Glover being awarded the Order of the Rising Sun, Japan’s highest honour, by the Emperor Meiji in 1908, the fi rst foreigner to be honoured in this way. Any of these accomplishments hould be suffi cient to ensure Glover’s inclusion in the Scots pantheon of nineteenth century heroes, so why is he so overlooked?

The answer lies in our relationship with Japan. Shortly after Glover’s death in 1911, Japan was a valued ally in the First World War, but its role in World War Two, in particular its treatment of Allied prisoners of war, cast a dark shadow that made it difficult to celebrate the achievements of the Scotsman who did so much to transform Japan into an economic and military powerhouse.

That Glover, more than a century after his death, is taking his proper place in Scots folk memory is attested not only by the BBC documentary or the former Chancellor’s praise.

TAGS