Scotland’s forgotten undersea tunnel to Ireland

The same year the Forth Bridge was completed, plans were drawn up for an even more ambitious rail crossing: from Scotland to Ireland – under the sea

Mention the Channel Tunnel to most people and their thoughts will turn to the high-speed rail link to Paris or Brussels. But in 1890 – fantastic as it may seem now – Victorian engineers had plans to build what would have been the world’s longest rail tunnel under the Irish Sea, from Galloway to Northern Ireland.

Despite being interested in railways since I was a child, I had never heard a whisper of this ambitious project until research for my book Mapping the Railways took me to the treasure trove that is the Map Reading Room of the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh.

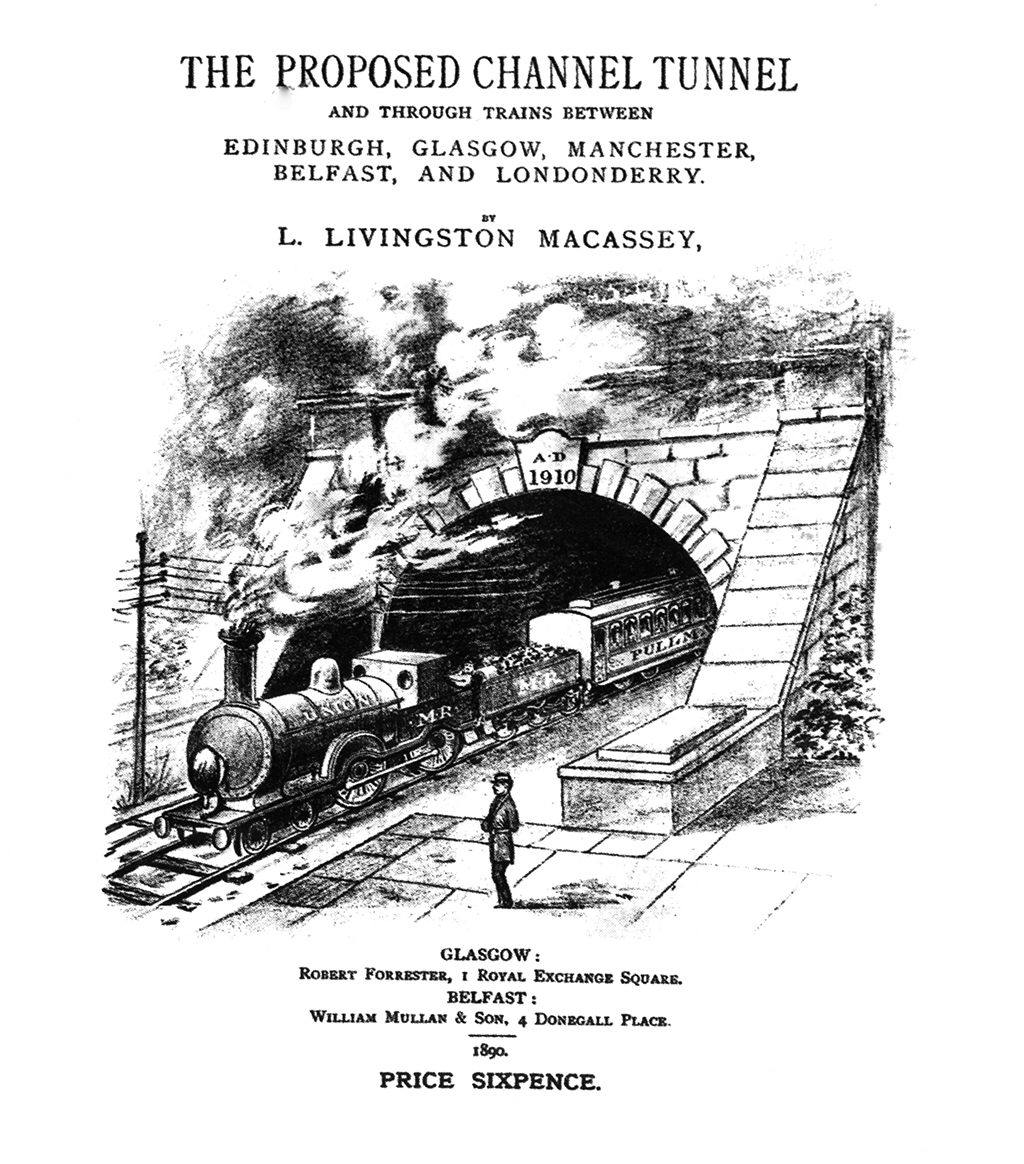

Senior map curator Chris Fleet had prepared a vast selection of railway maps for me to browse through, and one of the first documents he slid across the desk was a prospectus intriguingly titled The Proposed Channel Tunnel and Through Trains Between Edinburgh, Glasgow, Manchester, Belfast, and Londonderry, produced by L Livingston Macassey.

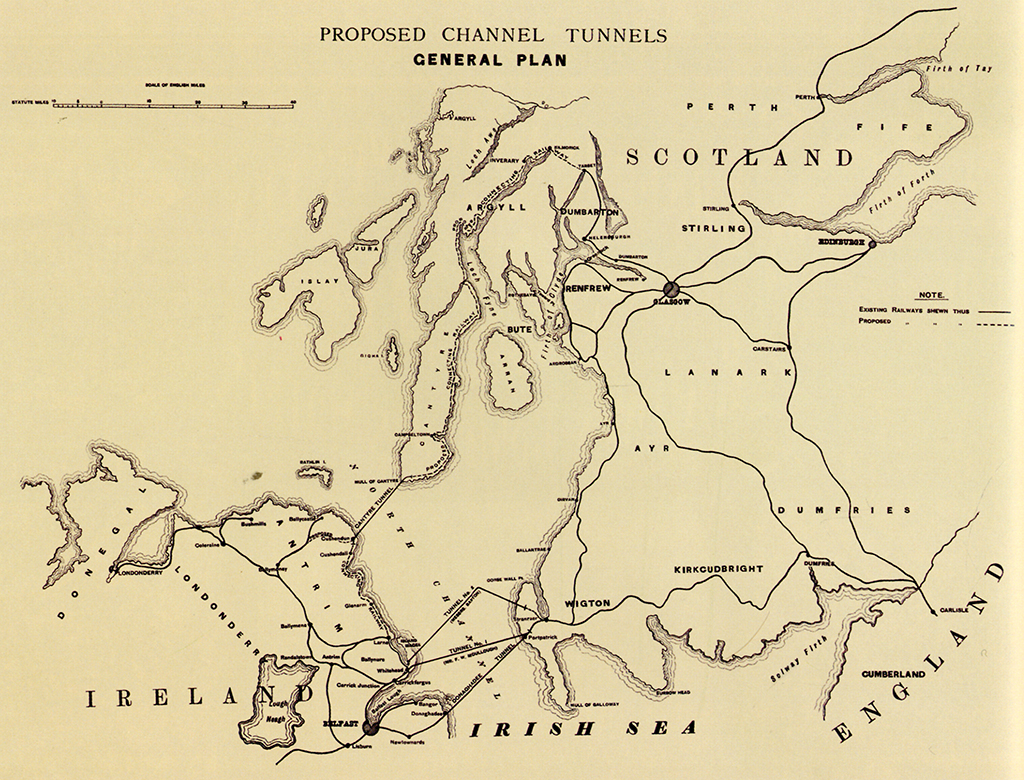

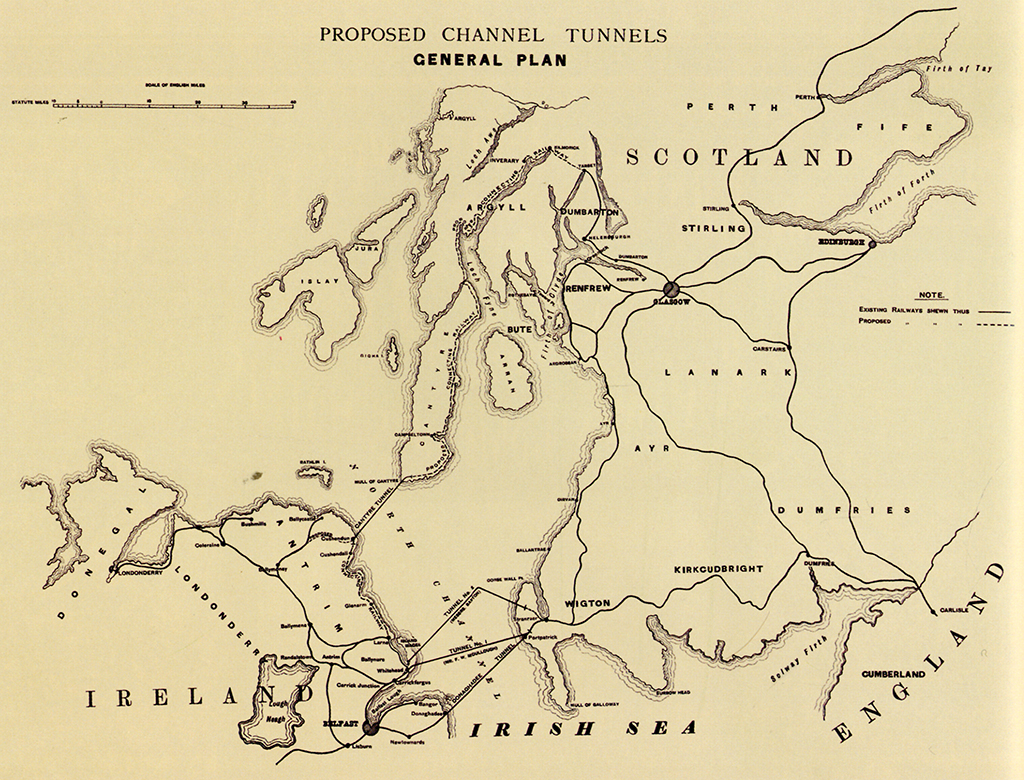

Macassey’s prospectus reviews and maps no fewer than seven options for the tunnel (the longest up to 31 miles), citing increased demand for travel at faster speeds as a key justification for the international rail connection, as well as a more prosaic reason for an alternative to the sea passage: ‘There is one thing in which time has made no change in the public mind, and that is the dread of sea sickness… They would undergo the fatigue of a hundred miles trip by rail rather than risk the horrors of twenty miles in a rough sea.’

Several routes were proposed for the crossing

Perhaps the most extraordinary of the seven proposals was for a submerged tubular bridge, comprising an outer shell of steel and cement and an ‘inner tube’ containing the railway, with the whole structure ‘to be kept in position by means of chains and anchors’. Prospective passengers are unlikely to have been wholly reassured about their safety in transit: ‘At intervals of 500ft were water-tight doors so arranged as to close in cases of emergency. The rere [sic] of trains to be so designed as to act as a piston in order that in case of an inrush of water the train might be forced out of the tube.’

At an estimated cost of £5.25 million, this option would have been a bargain compared to the projected £70 million (around £7 billion at today’s prices) for a ‘solid causeway between the Mull of Cantyre [sic] and Northern Ireland’.

A bridge at £30 million is also rejected, and the map focuses on four tunnel options ranging in cost from £7.6 million to £16 million. Three would have been tunnelled from near the mouth of Belfast Lough to the vicinity of Portpatrick or Stranraer, while the fourth – linking North Antrim and the Mull of Kintyre – would then have required a new railway of more than 100 miles to link the tunnel mouth with the West Highland Line at Arrochar.

Passengers from Belfast to Glasgow would have faced a train journey of at least six hours, little or no faster than the route by ferry and train. As I worked my way through the text and maps, and pondered the cost and complexity of what was being proposed, doubts crept into my mind. Yes, the Victorians had an engineering vision which produced marvels such as the Forth Bridge (completed the same year as the prospectus was written) and the four-mile Severn Tunnel, opened four years earlier – but crossing the Irish Sea was a project of an altogether different magnitude. Was the prospectus perhaps a Victorian spoof?

Further research soon allayed my doubts. Luke Livingston Macassey (1843–1908) was in fact a well-regarded Irish engineer, noted for his role in improving public health through schemes for the reliable supply of water to Belfast, in particular designing a pipeline system opened in 1905 to bring the pure water of the Mountains of Mourne to Ulster’s capital.

So why did this Channel Tunnel never materialise? The prospectus itself provides the answer: ‘…No amount of traffic likely to arise would make the tunnel a dividend-paying concern… the tunnel must be constructed at the expense of the state. No railway company or body of speculators would ever venture upon an undertaking of so doubtful a character.’

L. Livingston Macassey’s prospectus for the proposed Scottish channel tunnel

While the state would become involved in railway financing – recognising the wider economic spin-offs – this was a new and controversial concept in 1890. Within a decade government funds would help to underpin the construction of the Mallaig extension of the West Highland Line, but this was measured in tens of thousands of pounds rather than the multi-millions of the Irish dream.

It is nevertheless tantalising to speculate on the possible impact of ‘the other Channel Tunnel’. Over and above the sheer scale of its construction, there would have been the additional difficulty of Britain’s 4ft 8½in track gauge trains meeting Ireland’s distinctive 5ft 3in gauge. However, to this day there are plenty of places on mainland Europe where standard gauge meets broad gauge, notably at the Spanish-French border, and simple technical solutions such as swapping the carriage bogies have been developed to permit virtually seamless travel.

A tunnel from Belfast Lough to the Rhins of Galloway would have allowed a through rail journey of around three hours from Belfast to Glasgow, sufficiently fast to beat all competition – perhaps even today’s low-cost airlines – but it was not to be. Yet just in the last decade ago, the Centre for Cross Border Studies, an Irish think-tank, suggested that a high-speed rail bridge between County Down or County Antrim and Galloway would enable passengers to travel from Dublin to Glasgow in one and a half hours, and to Paris in seven and a half.

The current reality for land and sea-based public transport from Glasgow to Belfast is altogether more mundane. After 134 years of train-ship connection, the last ferry left Stranraer harbour in the early hours of 20 November, resuming service later that day from rail-less Cairnryan Port. Passengers from Glasgow now travel by train to Ayr, changing into a coach for the last leg to the ferry terminal.

If this seems less than ideal from an integrated transport perspective, spare a thought for ‘foot passengers’ arriving by ferry at Belfast Port at weekends – connecting buses to the city centre (four miles away) only operate Monday to Friday. Now that would

have astonished the Victorians.

David Spaven is co-author of Mapping the Railways: The Journey of Britain’s Railways from 1819 to the Present Day, with Julian Holland.

TAGS