Scotland’s language: Scottish authors help contribute to Doric’s revitalisation

By Marisha Worsnop

The brilliant thing about language is that it’s in control of the speaker.

Change, variation, and innovation are all at the hands of those using it. We as speakers say what goes and as long as enough people agree with us or understand us at the very least, we can do whatever we want with it.

At the end of the day the language we use tells a story about who we are and how we communicate our personalities to others. They become a part of our identities and express our worlds.

Perhaps, it’s not as simple as all that. We must consider the wider social attitudes towards the speakers, the usefulness of the language, and the authority the language holds. There are many different reasons for speaking a particular language, dialect or using specific slang.

All of us will change our manner of speaking or language we’re using depending on who we’re talking to. Linguistics refers to this phenomenon as ‘code switching’. This phenomenon is no stranger to many Scots as Scotland has quite a remarkable linguistic landscape.

Scotland is home to three indigenous languages: Scottish Gaelic, Scots, and English. Both Scottish Gaelic and Scots are recognised by the UK government and European Union as belonging to the European Charter for Minority and Regional Languages and English is our official language.

Prior to this recognition society stigmatised and both Scottish Gaelic and Scots were confined to the home as society pressured people to speak ‘proper’ English in the public milieux. As a result, these languages have struggled to maintain their speaker numbers as communities ridiculed people for speaking them.

Scots in particular has an interesting story as it has always had a strong oral and written literary tradition and continues to flourish today. This is happening even though in recent times due to a lack of standardisation, its written form is normally only for specific reasons.

However, this lack of standardisation lends itself to more creativity with language and a colourful array of proverbs, poetry, and stories.

The Scots leid ‘language’ is an umbrella term for a sister language of English made up of many dialects on a linguistic continuum.

Both English and Scots come from the Anglic branch of the West Germanic language family. On one end of the Scots continuum, you’ve got Scottish Standard English and on the other, broad Scots with a huge variety in grammar features and vocabulary depending on which part of Scotland you’re from and even in which sector you work in.

While the 2011 census recorded 1.5 million speakers of Scots, the linguist Robert McColl Millar reckons there could be as many as two million speakers because the lines of what counts as Scots is blurred.

Linguists trace back the language first setting foot in the Lowlands of Scotland in the seventh to twelfth centuries from Northumbrian Old English contact.

Later, the language spread throughout the country and became influenced by many different languages such as Gaelic and Scandinavian. Each area has its own flavour of Scots uniquely categorised by local linguistic features, reflecting the aspects of daily life in those communities.

Attitudes towards Scots are changing. Many governing bodies such as Creative Scotland and the Scottish government are making an effort to change social attitudes and opportunities for Scots to be written and spoken in beyond the home. Scots has been added to the Scottish Curriculum of Excellence and they’ve even introduced a new Scots language award.

Amongst the wide range of Scots vernaculars is Doric. Sometimes described as a fourth regional language, the variety is rumoured to have been spoken by Queen Elizabeth II and brimming with Scandi influence.

Its geographical home is the North East of Scotland and has some interesting linguistic features such as replacing the ‘wh’ with ‘f’ in question words, so ‘how’, ‘what’, ‘where’, and ‘when’ become foo, fit, far, and fan. Words can be very different too, like loon as opposed to ‘boy’ and quine instead of girl.

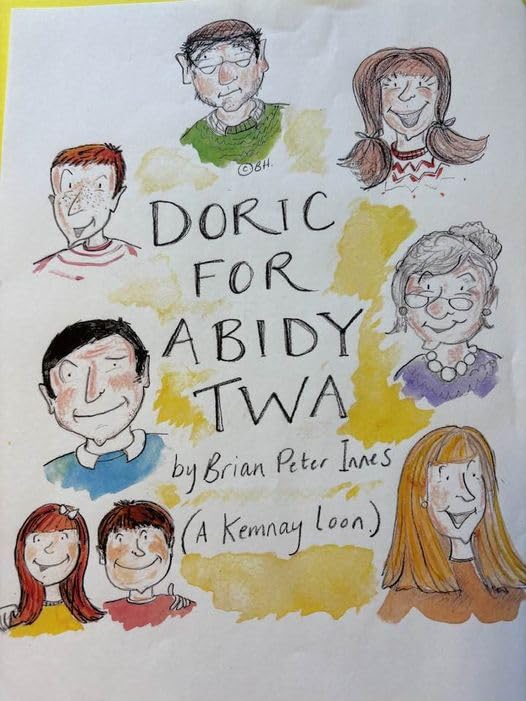

Doric for abidy twa by Brian Peter Innes.

There are also many contemporary examples of written Doric which are a bit of a strain to read for an English speaker, especially when you’re not used to hearing the language.

However, the good news is that Doric literary contributions seem to be thriving. A selection of poets, writers, and translators are making their mark, like Sheena Blackhall and Shane Strachan. Brian Peter Innes’ new book Doric for abidy twa is the sequel to his first collection of stories reminiscing about his childhood in Kemnay village, Aberdeenshire.

It recounts funny anecdotes and mischief of the author’s school days and relays information about local delicacies such as the differences between mealie and white puddings.

Although written in full blown Doric, the best part is that anyone can give it a go because Brian’s added a little glossary of Doric words at the back of the book.

Brian also leaves us with a section to write down the words we learnt from the book, words he could’ve used, and for us to write down our favourite Doric words and their meanings. Hence contributing to the malleability of language and Scots.

Its contributions like Brian’s which help to change the attitudes towards Doric and tell stories in the language close to the heart for individuals from those communities. They show us that minority languages are just as important as big official ones.

Doric and Scots seem to be doing just fine without an official orthographic system and spelling phonetically means that most writers do so in a similar way. This leaves language to be more personal and creative.

It’s more than a question of being Scottish, it lets you be individual. A true doctrine of what language should be.

The idea that language can stand still and not change is one of pipe dreams. Some 800 to 1,000 words get added to the English dictionary every year.

As we all contribute to and construct our tongues it’s important to remember that we’re imparting parts of ourselves to a larger communal narrative of those who came before us and to those who will come after.

Read more Culture stories here.

Subscribe to read the latest issue of Scottish Field.

TAGS