Scots started and ended the English Civil War

The 17th-century civil war may seem a very English affair, but that is misleading – it was started and ended by Scots.

At school, you may have studied the 17th-century Civil War: the ‘Wrong but Wromantic’ Cavaliers versus the ‘Right but Repulsive’ Roundheads, as 1066 And All That memorably described it; the execution of Charles I and the rise to power of Oliver Cromwell and his New Model Army; the Battles of Worcester and Naseby and Marston Moor; the future Charles II hiding in an oak tree in Boscobel Wood with the Parliamentarian forces perilously close by.

It all seems a very English affair, about the English Parliament’s conflicts with the English Crown.

Recently, however, historians have preferred to call it ‘The War of Three Kingdoms’, since both Scotland and Ireland were inevitably drawn into the dispute. It is easy to see why the older version prevailed for so long.

The English story is clear – the extravagant and naïve Charles pitted against the unglamorous and hard-headed Cromwell over a clear point of principle. The Scottish story, however, is much more ambiguous.

Indeed, if the ‘English Civil War’ might broadly be dated from 1640, when Charles I dissolved the ‘Short Parliament’, to 1660, when General Monck restored Charles II to the throne, the ‘Scottish Civil War’ could be said to have run from 1637 to 1744, and the final defeat of the Jacobite cause.

A riot against an Anglican prayer book in 1637

Perhaps the best way to unpick the ironies and ambivalences of the Scottish position during this period is to pose a simple question: to whom did Charles I surrender in 1646? Not to Fairfax, Essex, Ireton or Cromwell, but to the Scottish regiment encamped at Newark.

It was an exceptionally shrewd move. His military shattered, Charles resorted to guile. This was a bizarre change of fortunes, since it was the Scots who had catapulted the country from political tension to armed conflict in the first place.

Charles, who had of course been born in Scotland, had an even more tumultuous relationship with the Kirk than his father, James VI and I. In particular he resented the Kirk’s overbearing attitude: Andrew Melville, a previous Moderator, had upbraided James as ‘God’s silly vassal’.

The Church maintained that while the King had authority in matters temporal, they had authority in matters spiritual; and often where one ended and the other began was a point of serious contention.

As with James, the idea of being one King ruling over two different systems of religion irked Charles. The more headstrong Charles, abetted by Archbishop William Laud, sought to eradicate the differences by imposing his own prayer books on the Kirk in 1637. It caused a riot, with one woman, Jenny Geddes, purportedly throwing her stool at the minister and shouting ‘daur ye say Mass in my lug?’

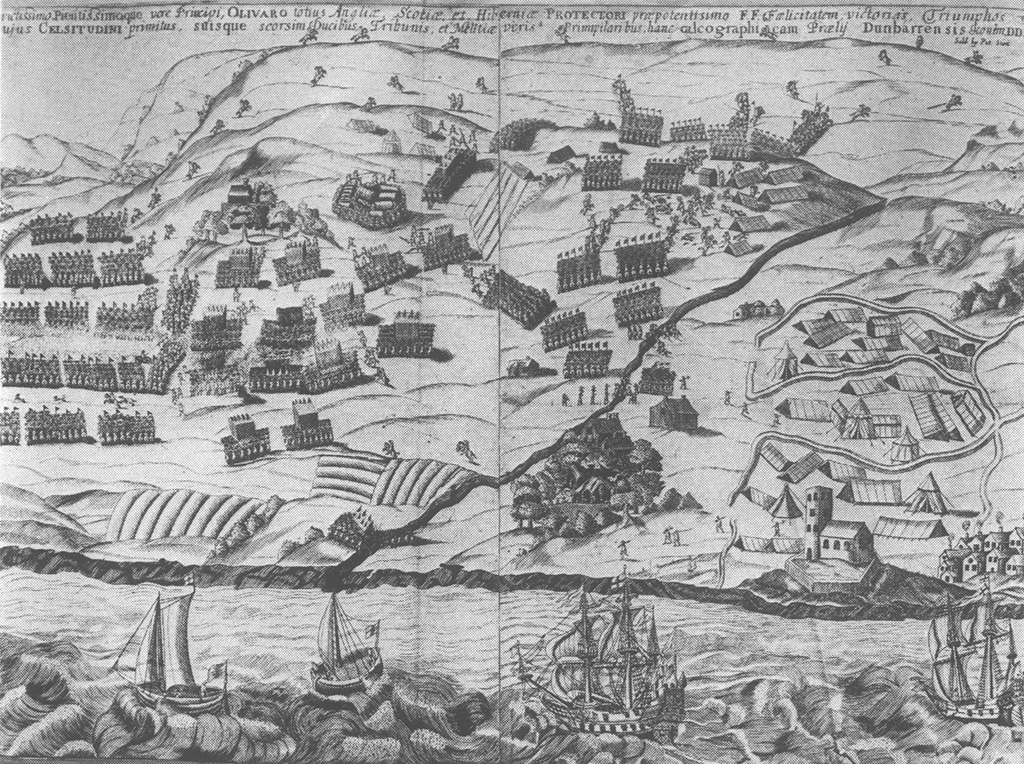

The Battle of Dunbar took place in 1650

It led to the Church drawing up a ‘National Covenant’; in part written by the theologian Alexander Henderson and including amongst its prominent signatories the Marquis of Montrose. The covenant – eventually signed by 600,000 people – stated that as long as the king protected the Presbyterian Church, the Presbyterian Church would protect the king. There was the rub.

Charles, forgetting that the word ‘thrawn’ could have been invented to describe the Scottish Church, sorted refused to sign, leading to the so-called First and Second Bishops’ Wars, the latter ending with Montrose and the veteran of the European wars Alexander Leslie in control of Northumbria and County Durham. Charles had to recall the English Parliament for financial support – the ‘Long Parliament’ – and precipitated his war with them.

Parliament now opened negotiations with the Church. Although there were many mutual areas of agreement, the Church of Scotland held both the Independents and the Puritans at arm’s length.

Nevertheless, Westminster and Edinburgh both signed a successor document to the Covenant, the Solemn League and Covenant, which brought the Scots into the fray on the side of Parliament. Even before this, Montrose had already switched sides, concerned that the Kirk was attempting to usurp the power of the Crown.

The Scottish and English armies embrace

It may have been the French diplomat Jean de Montereul who suggested a solution. The Covenant committed the Scots to the king: why not hold out the possibility of signing it? Henderson was summoned to discuss religion with Charles, who famously said he preferred to lose his crown to his soul. But a wily mixture of procrastination and secret negotiations with the ‘Engagers’ in the north bought Charles time.

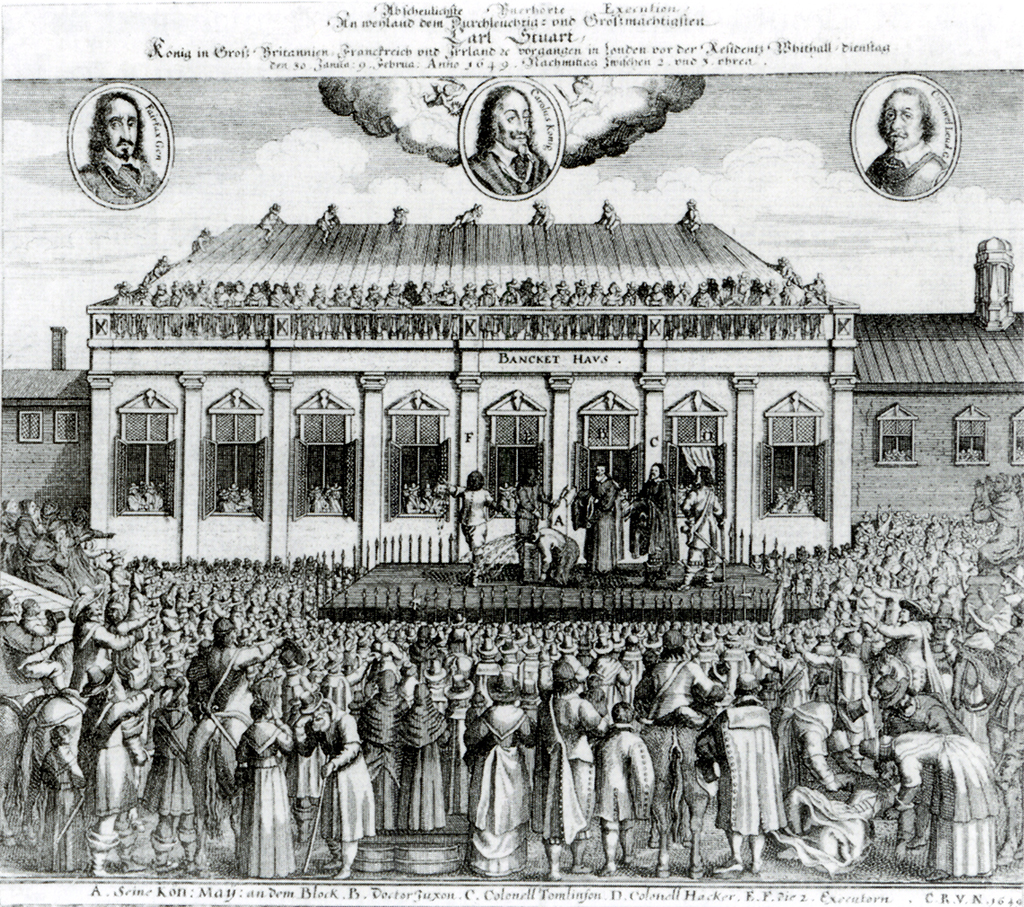

What did for Charles was English gold. The Scots had been promised much and were financially insecure, so in exchange for their prisoner, the English Parliament paid Scottish debts. Charles was handed over, eventually to be tried and executed. Henderson, on hearing of the transfer of the king, supposedly died of grief.

The execution of Charles was a turning point. The English had killed the legitimate King of Scots without so much as a by-your-leave. Charles II was proclaimed King of Scots in Edinburgh, and the head of the ‘Engagers’, the Duke of Hamilton, beheaded in London.

Under the Treaty of Breda, Charles II signed the Covenant; an act he did so in supreme bad faith. He needed allies not disputations on theology. Cromwell addressed the General Assembly over the Scots defection, saying: ‘I beseech you, in the bowels in Christ, think it possible ye may be mistaken.’

When the Assembly decided they were not, Cromwell launched a punitive strike against Dunbar, capturing it from Sir David Leslie beside whom he fought at Marston Moor. Three thousand Scots were killed and 10,000 captured. By the Battle of Inverkeithing, Cromwell had effective control of everywhere south of the Firth of Forth.

But the Scots were intransigent. In the last battle of the ‘English Civil War’, the Battle of Worcester, the majority of the 16,000 strong Royalist force was Scottish.

The execution of Charles I

Around 8000 Scottish prisoners were sent as indentured labourers to the West Indies and Canada, starting a relationship with those regions that would have significant influence in later centuries. Leslie was sent to the Tower, and released a decade later on the successful Restoration of Charles II and the death of Cromwell.

The Scots had instigated the war on their insistence that they were religiously and politically different from England. One unforeseen consequence was that Cromwell’s Commonwealth was the first time Scotland and England had the same governance, and explains why no General Assembly met from 1653 to 1690.

Charles II did not heed the lessons of what had happened to his father, and his attempts to create ecclesiastical uniformity led to the ‘Killing Time’ between 1680 and 1688. Even more bizarrely, after the English Parliament invited William III to take the crown, in favour of the Catholic King James VI and II, some Covenanters fought for the Stuarts against the new regime. The misery of war and religious schism makes for strange bedfellows indeed.

At the root, perhaps, of the problem was the difference between the Scottish and English experiences of Stuart monarchy. The Stuarts had ruled Scotland since 1371 and England since 1603. They may have been weak, injudicious, opinionated, divisive and profligate kings – but they had been our kings for a much longer time.

This feature was originally published in 2016.

TAGS