The King and the Bard were under her spell

Jane, Duchess of Gordon, threw legendary parties, hosted Edinburgh’s best literary salon and recruited troops through her beauty and charm. No wonder everyone from King George III to Robert Burns was under her spell.

The streets and closes of eighteenth century Edinburgh could be a dangerous place to walk.

Every evening, the public houses and gambling dens would disgorge their carousing patrons into the streets as all entertainment came to an abrupt halt with the beating of the ten o’clock drum. This was also the hour appointed for all household waste to be thrown from the tenement windows into the gutters below. Any inebriated passer-by who failed to hear the warning shout of ‘Gardy loo!’ (Gardez à l’eau) or answer ‘Haud yer hand!’ in time would have had the malodorous contents of stoups, pots and cans tipped over them.

During daylight hours, wild pigs scavenged in the closes and wynds of the Old Town, snorting with delight at any titbits they found. In the Lawnmarket, that stretch of the Royal Mile between Castlehill and the High Street, eleven-year-old Jane Maxwell, who would grow up to be Duchess of Gordon, and her sister Eglantine were a familiar sight as they rode on the back of the marauding pigs.

Jane, daughter of Sir William Maxwell, had arrived in Edinburgh with her mother and sisters in 1760, and the family rented an apart ment in Hyndford’s Close, halfway along the Royal Mile.

It was not unusual for Scottish landowning families to rent apartments in the city so their daughters could receive an education before being launched into Edinburgh society.

This was a convivial age, with a hard drinking society. While wealthy citizens took their supper at eight o’clock in the evening and drank into the wee small hours, the less affluent drank penny ale and raw spirits and often missed out the dinner hour altogether. The nobility spent their evenings singing blasphemous songs. The venue would be a gentlemen’s club, such as the Sulphur Club or the Hell-Fire Club, all condemned by the Kirk for apparently hosting orgies.

Ladies, accompanied by high-spirited gentlemen, frequented the dirty, squalid basement rooms that were the oyster bars. Here their raucous laughter and the clatter of their high heels echoed off the cellar walls as they slurped the raw oysters. This was the society that welcomed the teenage Jane Maxwell and applauded her for her free spirit and beauty.

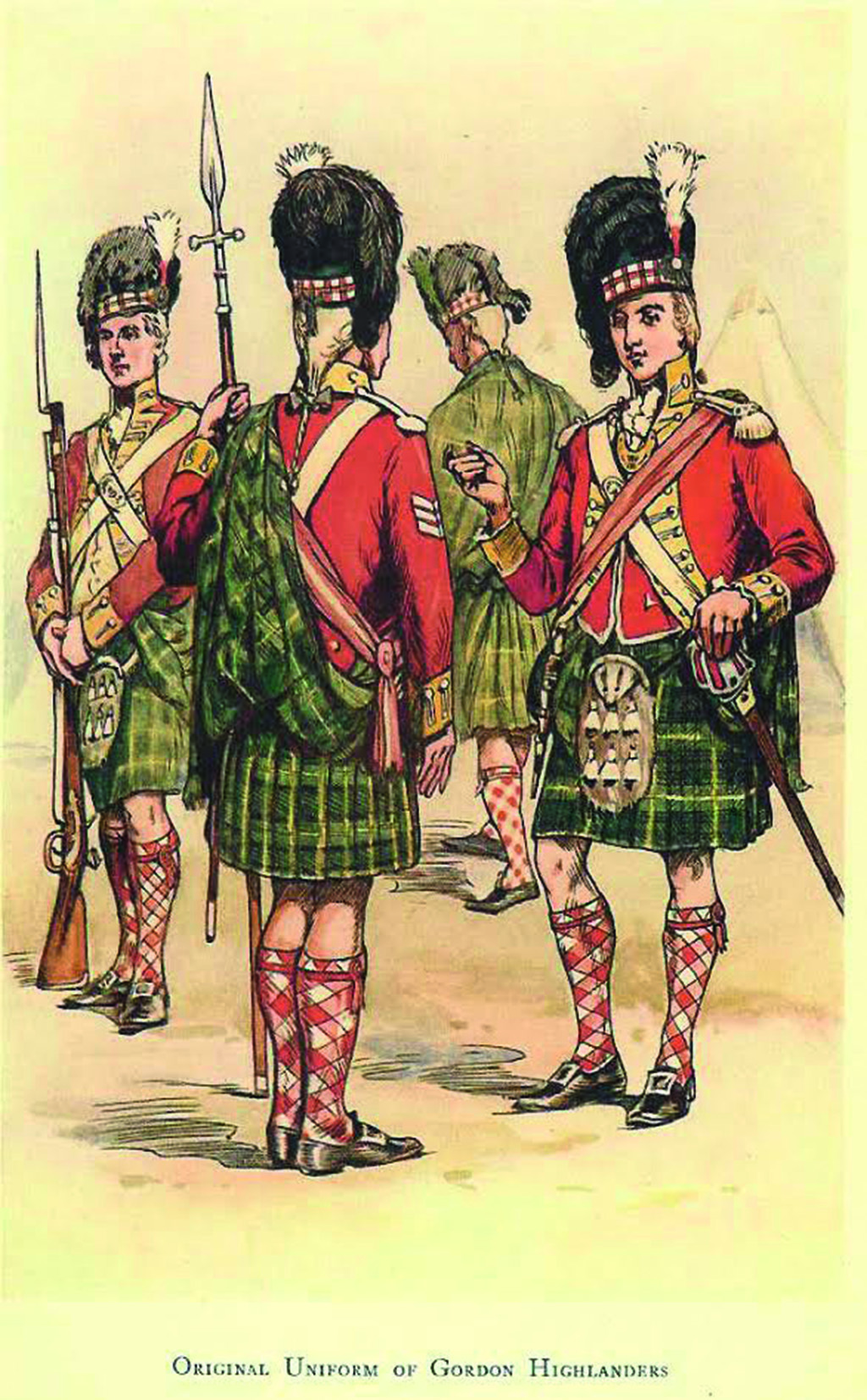

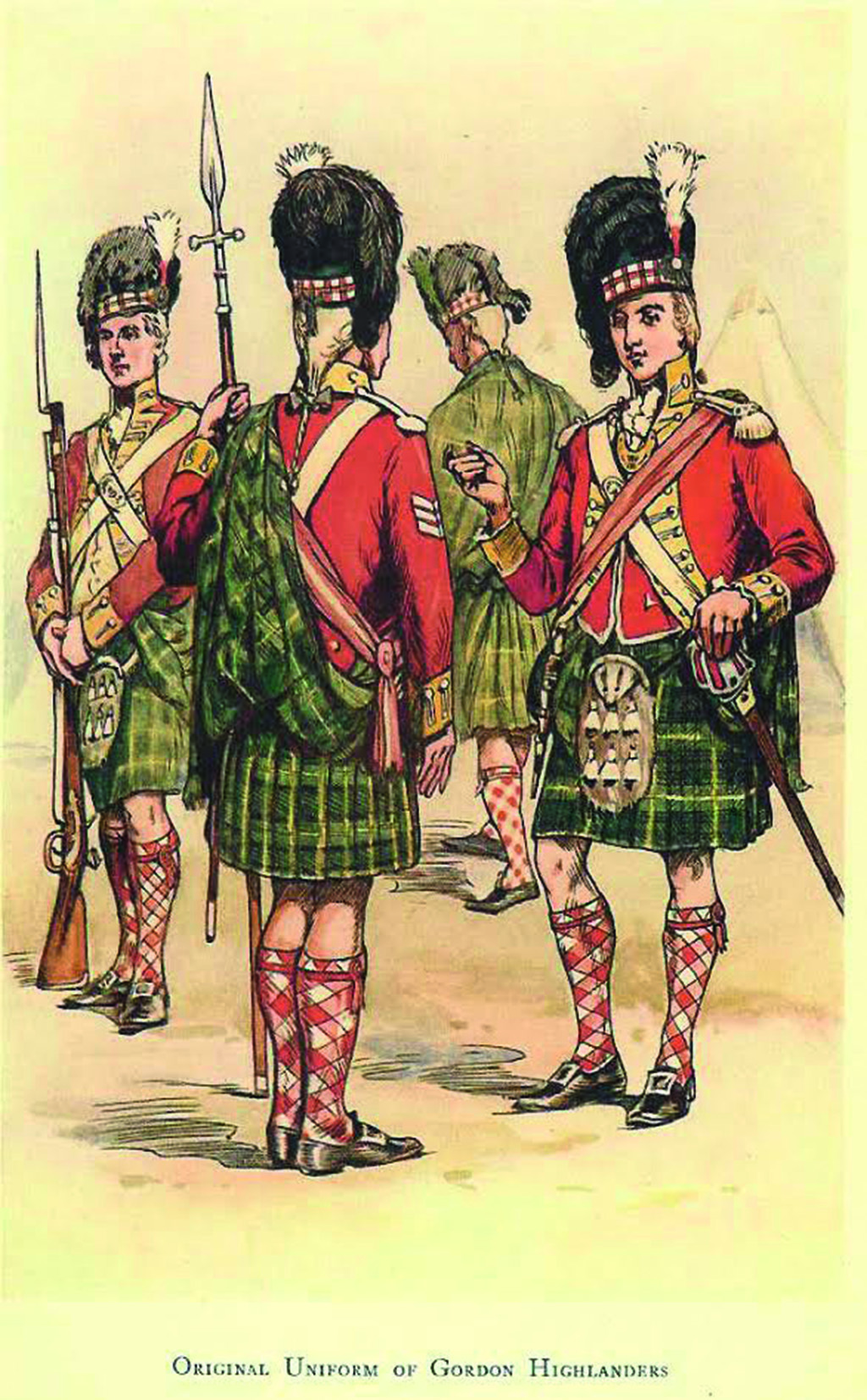

The original ‘gey’ Gordon Highlanders’ uniforms

One of the young Jane’s favourite haunts was the Assemblies. Although people were happy to dance at parties, most of them were reluctant to host one in their own home, so the first Assembly opened in 1710 with the aim of allowing the public to dance and socialise. After 1720, the Assemblies were held at Old Assembly Close, off the High Street, despite ‘promiscuous’ dancing being condemned by the Kirk. By the 1770s, the Assemblies had deserted the Old Town for more fashionable premises at George Street in the New Town.

Tickets cost half a crown for the dancing, which began at five o’clock and went on until ten or eleven. Refreshments were served but men sometimes carried an orange in their pockets to offer the ladies between dances. The ladies would alternatively suck on the orange and snort pinches of snuff from the dainty boxes hanging at their side.

It may have been at one of these dances that Jane met her first love, a young soldier. At the age of nineteen, in the mistaken belief that he had been killed in battle, she agreed to marry Alexander, the son of the wealthy Duke of Gordon.

Following the death of Alexander’s father, the pair became Duke and Duchess of Gordon and moved into Gordon Castle in Morayshire. There they had five children together.

It wasn’t long before Jane was organising parties at the castle, planting trees in the grounds and taking a keen interest in farming. She entertained on a lavish scale, often with up to a hundred dinner guests at one sitting. One guest was Robert Burns – the opulent surroundings inspired him to write the poem ‘Castle Gordon’, which he sent to the Duchess.

Jane’s reputation as a society hostess was established at Gordon Castle in Morayshire

Jane, who always spoke in the Scots dialect, apparently commented that she would have liked it better had it not been written in English. In the 1780s the Duchess moved back to Edinburgh and became the city’s leading hostess, as well as Burns’s sponsor.

His first readings of his poetry to Edinburgh society were in Jane’s drawing room. By 1787, Burns was back at his farm in Ellisland having decided to retire from poetry, but he had not given up writing altogether. He undertook freelance work as a journalist and lampoon writer for various newspapers.

When the following stanzas ridiculing the Duchess of Gordon appeared in The Star, Burns denied having written them:

She klitit up her kirtle weel

To show her bonie cutes sae sma’

And walloped about the reel,

The lightest louper o’ them a’!

Whilesome, like slav’ring doited stotss

Strouit’ out thro’ the midden dub,

Funkit their heels among their coats

And gart the foor their backsides rub:

Gordon, the great, the gay, the gallant,

Skip’t like a maukn owre a dyke:

Deil tak me, since I was a callant,

Gife-er my een beheld the like.

Whatever the truth of the matter, Burns admitted using women of his acquaintance for his heroines and there are enough similarities between this poem and his description of Nannie (of the famous cutty-sark) in ‘Tam O’Shanter’ to suggest the character of Nannie may have been based on Jane.

The Duke and Duchess moved to London where they gave parties with a decidedly Scottish theme. As King George III adored Jane, she was able to promote her Scottish heritage more than others would have dared, especially since the 1746 ban on the wearing of tartan.

A depiction of busy life on the Royal Mile by Louise Rayner

In 1793, when the army was found to be found short of recruits, Jane placed a bet with the Prince Regent that she could enlist more men than he. Wearing a military uniform and feather hat, she toured Scotland organising reels, placing a golden gunea between her teeth and promising to kiss any man who would take the King’s shilling – and won her bet. By this means the Gordon Highlanders were born.

Although the origins of the Gay Gordons dance is unknown, it is believed that the Gordon Highlanders’ uniform was the inspiration for the name – the word ‘gey’ (rather than ‘gay’) meant ‘fierce’.

By the turn of the century Jane was depressed and ill. One of her sons died young. Her eldest son had gone to war, and her husband was living with his mistress at Gordon Castle. Still, over the next few years she continued to throw lavish parties as she secured good marriages for her daughters.

It was rumoured that she enjoyed secret assignations on the windswept moors with the soldier lover she’d once believed dead. The young girl who’d ridden on scavenging pigs in the Lawnmarket never lost her free spirit. Jane, Duchess of Gordon, was a rare female voice in an essentially masculine world.

TAGS