The late, great Charles Jencks was romancing the stone

Architect Charles Jencks sadly passed away earlier this month, but he leaves behind an incredible legacy of work.

In 2015, Scottish Field visited the stunning artland Charles created out of an open-cast mine, which stands as a lesson in cosmology and creative passion.

Small plumes of smoke rise lazily from behind a pile of stones, the peace intermittently shattered by the screech of metal on rock as lettering is carved into the stone surface.

Larger, imposing boulders dot the area in rows, clusters and spirals with a crescent moon of water at the centre, its tranquillity reflecting the ambience of the day as the sun beats down on the Upper Nithsdale hills.

This is the Crawick Multiverse, a £1 million artland in the heart of Dumfries and Galloway created by world-renowned landscape artist Charles Jencks and commissioned by the 10th Duke of Buccleuch, Richard Scott. The pair, introduced by Charles’s late wife Maggie, have been friends for 30 years.

When Richard decided something had to be done to address the ‘brutal eyesore’ left by a company that had mined the site for coal, he thought of Charles. It is the latest in an impressive portfolio from the American-born designer, a leading figure in landscape architecture who has created works across the globe from the UK’s Northumberlandia and Garden of Cosmic Speculation to Beijing Olympic Park’s BlackHole Terrace and the Suncheon City in Korea, which he worked on with his daughter Lily. Created using materials found on the expansive Crawick site, Charles’s design has transformed the former open-cast coal mine.

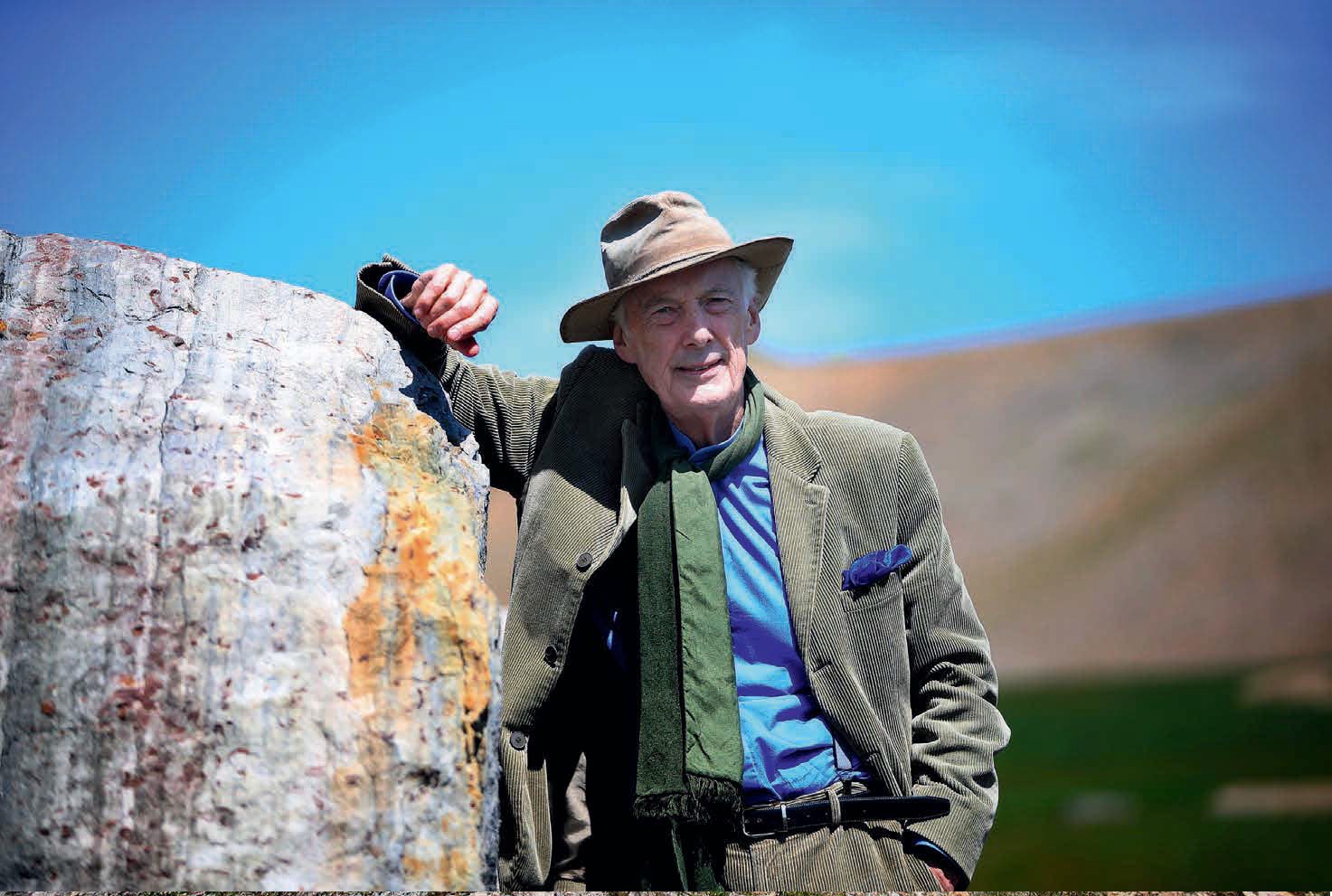

Friends for more than 30 years, the Duke of Buccleuch and Charles Jencks enjoy the view from the Belvedere, which offers a 360-degree view of the surrounding countryside (Photo: Ian MacNicol)

Themes of space, astronomy and cosmology (a ‘multiverse’ is a hypothetical space or realm consisting of a number of universes, of which our own universe is only one) are linked via the use of grassy banks, mounds, boulders and the elliptical lagoon that shimmers behind a 5,000-capacity amphitheatre.

Today’s warm, still conditions are in stark contrast to those experienced by Charles on his first visit to the site in 2005. ‘The sun was out but it was cold and there was a fierce 50-mile-an-hour wind,’ he remembers. ‘We could lean right into it off the ridgeway. It was desolate – a desert, really. There was rubble all around and like any coal site it was pretty depressing.

‘At first I couldn’t see what could be done with it because there wasn’t much money. But when we got to the top I looked around and saw this bowl of mountains, which was a natural cosmic bowl. If you have no money and you just have to make a very primitive gesture, you want to make everything on the north, so the idea of the Belvedere, which stands on the northern point, came almost first thing.’

Soon he began to see that the desert the coal company had created was actually an amazing asset in the wettest part of the world. ‘How many places have a desert in a rainforest? It’s sort of a reverse gardening.’ The two mounds – representing the Andromeda galaxy and the Milky Way – were constructed first, but the lack of contrast was proving a problem.

The Multiverse includes stones carved with lines representing the different types of universe and their fates (Photo: Ian MacNicol)

‘Landforms always need a counter to be perceived,’ Charles explains. ‘It’s a yin-yang thing – opposition. If you don’t have water, what you need is white gravel; and if you don’t have white gravel, you need something that will contrast with the green – because there is nothing more boring than endless green meadows.’

It was the site itself that provided the solution and prompted Charles to think much bigger in terms of concept and design. ‘After creating the galaxies, we discovered there were about 2,000 boulders on the site, which was incredible. I told Richard about the boulders and how we could use them to create the multiverse. I presented him with the design and we talked it over for about three hours and at the end of it he said, “All right, let’s do it!”’

Almost complete – but with room to grow and evolve – the site now boasts a series of paths navigating features and landforms that represent the sun, universes, galaxies, comets and black holes.

At the northernmost point of the site, the Belvedere offers a 360-degree 20-mile view of the surrounding countryside and settlements. The finger of a giant stone hand points directly at the North Star. Below, a supercluster of galaxies has been created using a distinctive arrangement of abstract stone triangles. Their shadow patterns show the forming of our universe and its place within the cosmos.

Big bang theory – Crawick Multiverse in the making (Photo: Ian MacNicol)

The whole thing represents complex scientific theories, but an in-depth understanding of the finer points is not necessary in order to enjoy the site. ‘No one will know what the science is, but that doesn’t matter,’ insists Charles. ‘The important thing is for people to know it has meaning. Of all my work, it shows that the primitive, the very basic, can be heroic if you work at it. This is powerful, visceral art.’

Richard agrees: ‘One of the joys of it – and I’m not a cosmologist or a scientist and therefore for me it has been a huge learning curve – is that actually it’s just rather an extraordinary space.

Charles’s works are places that inspire peace.’ Much bigger than just visual art, the Crawick Multiverse has also been developed as a social regeneration project, and both men believe it will breathe new life into the nearby communities of Kirkconnel and Sanquhar, which Charles says were ‘squelched and squeezed to death’ when coal-mining stopped there.

Standing on top of the first mound, Richard surveys the site proudly, pointing out its features and best vantage points. ‘I’m very enthusiastic and passionate about it, and not just because it solves the headache of the eyesore. I really have come to see that it could be the catalyst for economic regeneration in this very deprived part of the country, because land art is quite big business worldwide,’ he explains.

Charles Jencks first visited the ‘desert’ of the former open-cast mine in 2005. (Photo: Ian MacNicol)

‘Here in the south-west of Scotland we have an incredible wealth of land art, partly because of Charles, but also we have people like Andy Goldsworthy – he’s one of our locals. Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Little Sparta is just up the road and there are examples of other artists working here, so I think for the south-west of Scotland this could be a really valuable selling point, and the scale of this development is big enough to catch the eye of those who are interested in land art around the world.’

He hopes local people will spend a lot of time there too. ‘Although it’s designed by this internationally acclaimed artist and we’ve done the funding, the hope is that it will be embraced by the community,’ he says. ‘The head teachers of the local primary schools, for example, have been wonderful in the way they have responded. They see this as an extraordinary open-air class room because it’s not just about arts, it’s about science, geology, biology and maths. It has got incredible potential from that point of view.

‘When people talk about restoration they mean putting it back to the way it was – in this case plain green fields. But that – as we now see, thanks to Charles – would have been a terrible lost opportunity.’

For more information visit www.crawickmultiverse.co.uk

TAGS