The Scot who committed high seas robbery

When con artist extraordinaire James Henderson vanished with a Clyde steamship, it was just the warm-up act for a drama played out across four continents that stunned the world.

The notice in Glasgow’s Evening Citizen on 12 February 1881 was as short as it was shocking: ‘Vessel Lost, Stolen or Strayed from the Clyde.’

The vessel in question was a steamship that the Highland Railway Company used as a ferry. Suitably named the Ferret, one blink and it was gone.

When a well-dressed man calling himself Mr Smith arrived from London in September the previous year saying that he wanted to charter the ship for a luxury Mediterranean voyage and that he was a close relative of the Rt. Hon. William Henry Smith, First Lord of the Admiralty, the owners couldn’t provision the ship fast enough. Trusting Glasgow merchants happily supplied all the fine china, linen and crystal glassware (not to mention the best of wines and food) that the customer wanted.

The bill was a tidy £1,900 (£169,000 in today’s terms). If they didn’t check him out with the Admiralty, the company at least were assured by a London bank that Mr Smith did have a large sum in his account. But rather than demanding some of it up front, they were happy to accept a bank note he gave them dated three months ahead.

One month later, he was gone, ‘with flags flying gaily and to the rousing cheers of the Clydesiders’, wrote Robert Travers in Rogues’ March. Mr Smith, real name James Henderson, would have been delighted with his send-off.

The Scottish merchants had their invoice books ready when the Ferret arrived in Gibraltar. But, by the time letters started coming back to them from the London bank saying that Mr Smith had been a depositor three months ago but wasn’t any more, the ship had turned west and disappeared over the horizon.

The Ferret eventually foundered in fog off the tip of southern Australia

The Ferret was now a fugitive, with worldwide insurers Lloyd’s of London after her. Knowing none of this, the crew (apart from Captain Robert Wright who, with purser William Wallace, had been picked up in Cardiff) were mystified by Smith’s decision to change his name and head in the wrong direction.

They protested when Henderson got them to repaint the yellow funnel black, the blue lifeboats white, make her resemble a cargo ship and repaint her name as Bantam. But, as engineer William Griffin later recalled: ‘He called us aft to tell us the ship was his; that he could do as he liked with her; that we must obey his orders; and that if any man betrayed him he would shoot him. They all agreed to be faithful. Each man had a glass of grog.’

Henderson changed the papers of both the ship and all on board. In December, they arrived at the Brazilian port of Santos, where 4,000 bags of coffee were loaded on board – coffee the local merchants assumed would be taken to Marseille. Instead, Henderson headed for South Africa. Running out of coal halfway there, he simply used 300 bags of the coffee to power the ship, arriving in Cape Town on 29 January.

There, he sold the coffee for £13,000 (more than £1m today), and the crew had to repaint the ship all over again. Now it was to be the India, the name of an actual ship Henderson found in the Lloyd’s Register of Shipping.

The con artist extraordinaire thought he’d pulled off the perfect crime when he arrived in Melbourne on 20 April. There, at the furthest possible point from Glasgow, he planned to sell the disguised steamer and become unimaginably rich. He had thought of everything – well, nearly everything.

He hadn’t counted on the sharp eyes of Constable James Davidson. The Scotsman, who in fact hailed from the Clyde, had recently arrived in Melbourne himself. He’d read newspaper reports of the ship’s theft, and, despite Henderson’s alterations, he recognised Glasgow’s Ferret immediately. He alerted customs; a description of the ship was sent from Lloyd’s and a watch was placed on the so-called India. Only Henderson and his two accomplices dared to disembark and seek a buyer, the crew remaining aboard with steam up as if ready to leave at a moment’s notice. The watchers then saw a woman go ashore and realised that Henderson had been brazen enough to bring his wife from Cardiff too.

The police boarded the ship and arrested the crew – who soon spilled the beans. But of the ringleader there was no sign. A man like James Henderson, who’d shown he could not only steal a ship, but get it fitted out luxuriously, press-gang the crew into slave labour, dodge port authorities and get halfway around the world, making a fortune as he went, wasn’t going to be that easy to snare.

It caused a sensation in Australia, especially when news leaked out that the mastermind and two men were still at large. But not for long: Mrs Henderson had stayed behind and a detective had kept watch on her lodgings. Within two days, Henderson and Joseph Walker, alias William Wallace, were arrested. Henderson’s plan had been clear; in his pocket was Bradshaw’s Guide to Victoria. A Sergeant Purcell went to Henderson’s hotel, and in his travelling case he found bills of exchange to the value of £2,100 (£189,000 today) and a pile of sovereigns.

In a packed Melbourne Magistrates’ Court, after the crew had had their say, Mrs Henderson made a name for herself, according to The Australasian, ‘by remarking aloud more than once that the witnesses were telling lies’.

But the capture of Captain Wright (real name Edward Carlyon) was what really livened up proceedings. The court was told about a disturbance at a Mrs Ryan’s lodging-house in Melbourne where a drunk man with a pistol was trying to fight everybody.

When the landlady saw this, she sent for a constable, who reported what she’d told him: ‘As soon as he got in, he tumbled, boots and all, into the bed. I said that was not a becoming manner to go to bed, and that he had better take his boots off, after which he jumped off the bed with his gun and started making a fuss.’ A search of the man’s room turned up £8,000 (£720,000 today) in bills of exchange, along with hundreds of sovereigns and Brazilian coins.

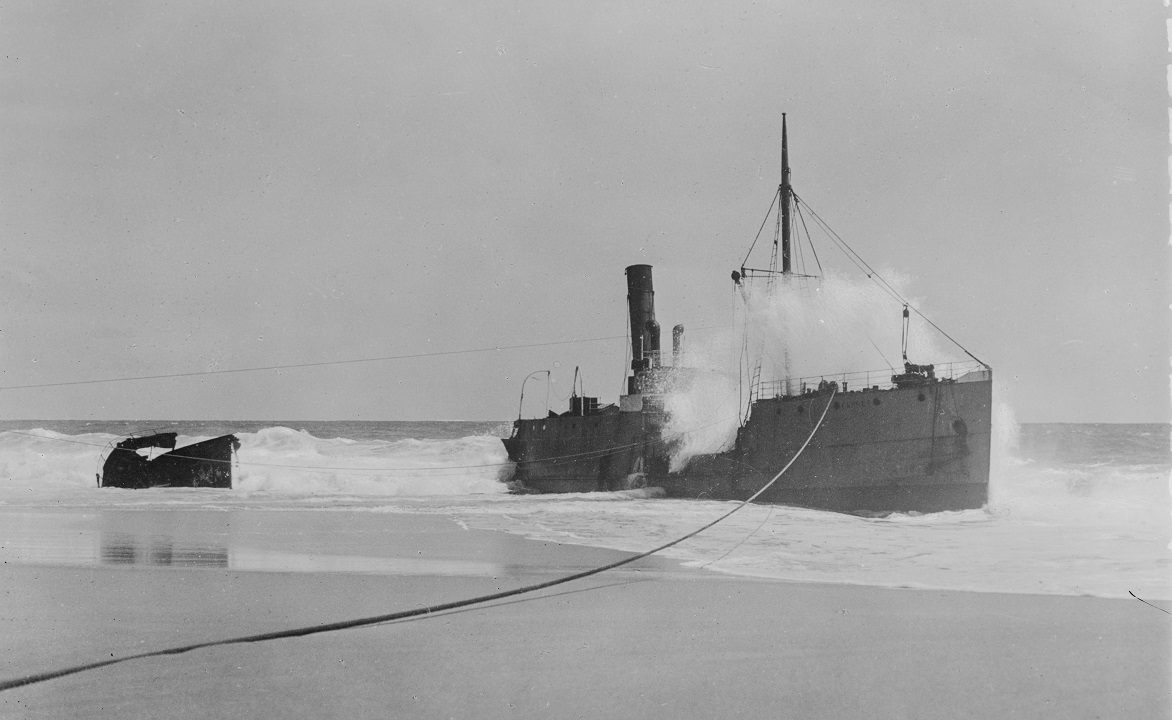

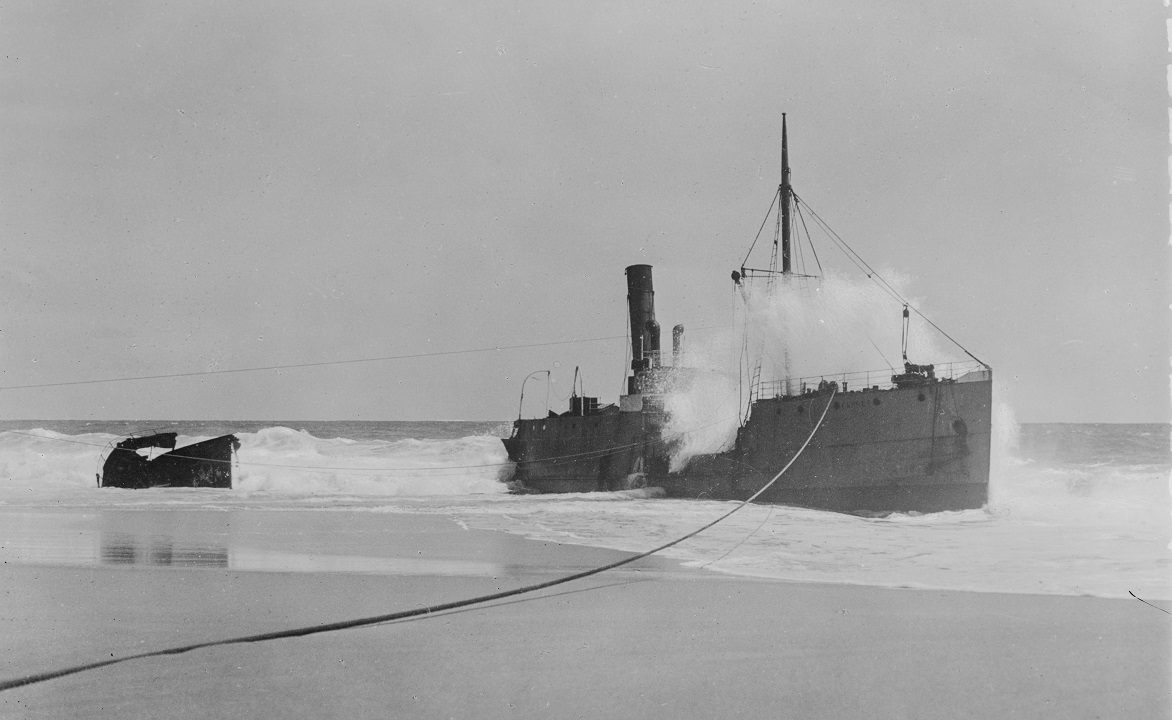

The remains of the boiler of the wrecked Ferret, on Ethel Beach, Innes National Park, Yorke Peninsula, South Australia

A reporter for the Melbourne Telegraph who saw Carlyon being brought into the police station, wrote: ‘He was dressed in a black cloth suit, black bell-topper, wore an eye glass, and was complacently smoking a pipe, but was under the influence of liquor, and had shaved off the ample beard which had nearly reached his middle.’

At the trial, which began on 18 July 1881 – almost a year after the Ferret had left the Clyde – the eternally elusive Henderson tried every trick in the book to get himself off the hook.

His lawyer attempted to have the case dismissed because there was no proof that the Highland Railway Company owned the vessel, that Henderson had taken the ship ‘on credit’ as a broker to sell it in Australia for the money to be sent back to Glasgow.

As for why he’d kept repainting the ship, Henderson told the court his plan was ‘to run guns across the Pacific to Peru, engage in a war against Chile, and that… a cargo of rifles sold to Peruvian buyers accounted for all the money’.

The jury’s verdict, amazingly, was Not Guilty, but the judge had other ideas and sent the three men to jail: Henderson and Walker got seven years, while Carlyon got three and a half.The Ferret was free to return to sea, earning an honest living working Australian waters.

She disappeared from the headlines until 1904 when she tried to help a Norwegian ship, the Ethel, that had got into trouble in rough seas off the southern tip of the Yorke peninsula in South Australia. The Ferret couldn’t get close enough to rescue the Ethel’s crew and had to sail on to the nearest lighthouse to raise the alarm. A sailor from the Ethel drowned trying to swim ashore with a salvage line.

During calmer weather the next day, the crew did manage to get a line ashore, but another storm blew in, snapping the rope and sweeping the ship onto the beach – where she has lain, a pile of twisted metal at the foot of a cliff, ever since.

Just metres away from the Ethel lies the wreck of a second ship, which foundered on nearby Reef Head in fog 16 years later, in November 1920. In the most unlikely of coincidences, the vessel lying next to the Ethel is none other than the Ferret. While her crew was safely recovered, her cargo of alcohol was not, thanks to the locals at nearby Inneston.

Caroline Paterson, an Innes National Park ranger, once observed drily: ‘Absenteeism at the gypsum mines had never been higher than when the Ferret’s loot was washing up on the beach.’

Somehow it seem rather fitting that the ship should end by giving up her treasures this way.

(This feature was originally published in 2016)

TAGS