The popularity of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s most famous creation, shows no sign of abating.

But it’s time the Edinburgh doctor on whom the famous detective is based became just as well known.

In 1893 Robert Louis Stevenson wrote to Arthur Conan Doyle to congratulate him on his new literary creation, Sherlock Holmes. ‘Only one thing troubles me,’ he added. ‘Can this be my old friend, Joe Bell?’

Stevenson was referring to Dr Joseph Bell, an Edinburgh pathologist with legendary powers of deduction and teaching abilities, whose involvement in solving several high-profile murder cases made him perhaps even more extraordinary than his fictional counterpart.

Arthur Conan Doyle came to Edinburgh University to study medicine in 1877 where, in his second year, Dr Bell appointed him outpatient clerk at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary.

The medical student was struck by how Bell could deduce facts about patients without having asked a single question. ‘Dr Bell would sit in his receiving room, with a face like a Red Indian, and diagnose people as they came in, before they even opened their mouths,’ he wrote. ‘He would tell them their symptoms and even give them details of their past life, and hardly ever would he make a mistake.’

This ability was one of the reasons why Bell was so popular among his students, and his lectures, where he taught ‘The Method’, were always well attended. Bell stressed the ‘accurate and rapid appreciation of small points in which the diseased differed from the healthy state’, as well as the importance of observing people before touching them: ‘Use your eyes, your ears, your brain… and always ratify your deductions.’

In one case a young doctor diagnosed ‘hipjoint disease’ in a patient who had come in with a limp. ‘Hip, nothing,’ Bell replied. ‘His shoes have been slit by a knife where the pressure against the foot is greatest. The man is a sufferer from corns, gentlemen. But he has not come here for that’, Bell continued. ‘This is a case of chronic alcoholism. The rubicund nose, bloated face, tremulous hands all show this. These deductions, however, must be confirmed by concrete evidence. In this instance my diagnosis is confirmed by the neck of a whisky bottle protruding from the patient’s right coat pocket’.

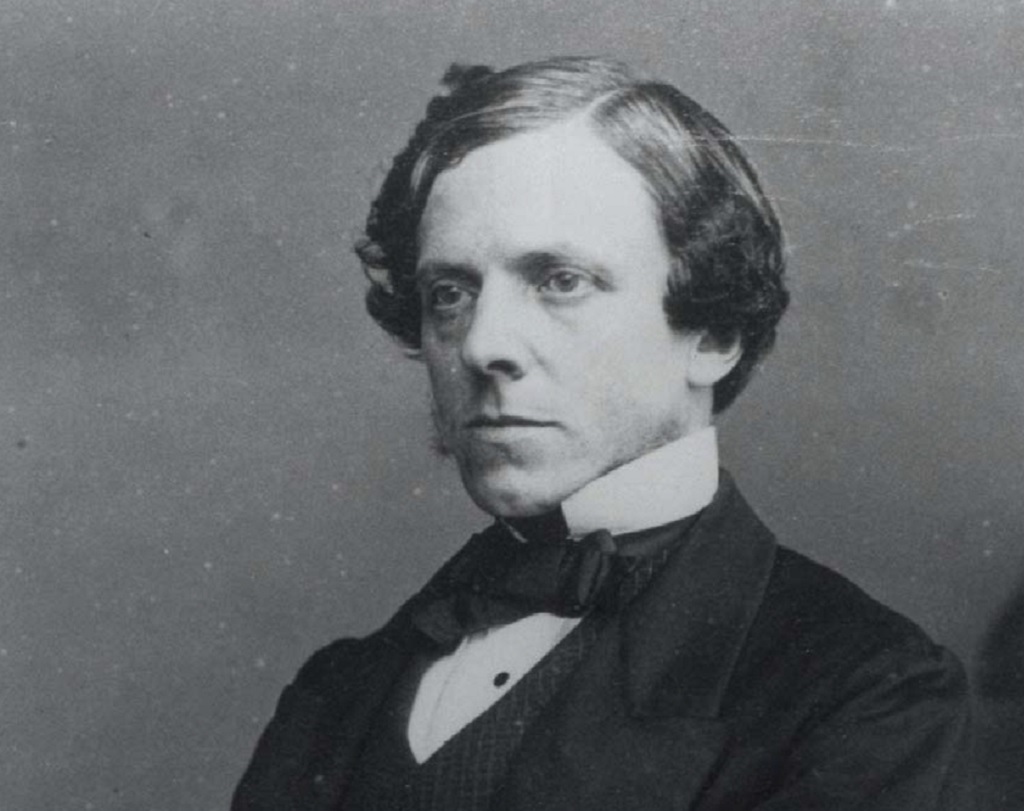

Dr Joseph Bell

Bell would regale dinner guests with his stories. On trains, he would amuse his children by telling them details about where the other passengers in the carriage were from, where they were going, their occupations and habits. ‘All this without having spoken to them,’ his daughter recalled. ‘When he verified his observations, we thought him a magician’.

Of course Bell wasn’t always on the money with his deductions, but his self-deprecating humour allowed him to happily recount the rare moments when he was wrong, such as the time he correctly ascertained that one patient was a bandsman. ‘You see, gentlemen, I am right,’ he said to his students. ‘The man had a paralysis of the cheek muscles, the result of too much blowing of wind instruments. What instrument do you play, my man?’ The patient looked straight at the esteemed pathologist and said: ‘The big drum, Doctor.’

After graduating, Arthur Conan Doyle set up his own practice in Sussex but struggled to make it a success. To make ends meet, he turned to writing fiction. When it came to creating his most famous character, Sherlock Holmes, he told the Strand, ‘I thought of my old teacher Joe Bell, of his eagle face, of his curious ways, of his eerie knack of spotting details. I used and amplified his methods to build up a scientific detective who solved cases.’

For his part, although he proclaimed annoyance at all the attention – Bell was hounded by journalists, and once stated that ‘I am haunted by my double, Sherlock Holmes’ – the doctor was secretly delighted and would often suggest possible Holmes story lines to the author.

The similarities between Holmes and Bell begin and end in the belief in ‘the science of deduction and analysis’. Bell didn’t wear a deerstalker, didn’t brandish a magnifying glass, did not smoke – ‘cigarettes make my feet grow cold’ – and certainly didn’t have a penchant for cocaine.

And while Holmes was a bachelor living in the pokey confines of 221B Baker Street, Bell had two large homes and was happily married with a son and two daughters. This happiness was cut short in 1874 when Edith, his wife of only nine years, died. Bell wrote in his journal: ‘She died about 8.5 o’clock in the evening… the blow is a fearful one in its suddenness and severity.’

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes

Devastated, he buried himself in his work. He never remarried. Tragedy struck again in 1893 when his son, Benjamin, died at the age of 24.

Born into a family of surgeons, Bell attended Edinburgh Academy and the University of Edinburgh, where he graduated MD in 1859, aged 22. Six years later, he became assistant to and protégé of the renowned James Syme at Royal Edinburgh Infirmary. In 1871 Bell became House Surgeon and was immensely popular with staff and patients alike, receiving personal congratulations from Queen Victoria for the state of the hospital. ‘The dear old lady was so friendly and I was not one bit flustered,’ he later recalled.

He was also renowned for his progressive views: he organised a series of lectures for nurses – becoming good friends with Florence Nightingale in the process – and controversially agreed to teach the first female medical students. He was also editor of the Edinburgh Medical Journal from 1873 to 1896.

Bell fancied himself as an amateur sleuth, and criticised the ‘tunnel vision’ of the average policeman, who ‘gets his theory first and then makes the facts fit it’. Along with the celebrated police surgeon Sir Henry Duncan Littlejohn, Bell was involved in a number of high-profile cases, including the Chantrelle murder of 1877 and the Ardlamont Mystery of 1893.

In the former, the two doctors proved that Elizabeth Chantrelle, thought to have died of gas inhalation, had in fact been poisoned by her husband. As the noose was placed around the killer’s neck, he said: ‘Bye, bye, Littlejohn. Give my compliments to Joe Bell. You both did a good job in bringing me to the scaffold.’

In the latter case, Bell, Littlejohn and Patrick Heron Watson (a ballistics expert who was possibly the inspiration for Dr Watson) proved that the gunshot wounds that killed Cecil Hambrough, a 20-year-old heir to a fortune, were not self-inflicted as claimed by his tutor, Alfred Monson. Monson was suspected of being the guilty party but incredibly the charge against him was found not proven.

Sir Henry Duncan Littlejohn

In the period between these two cases, Bell and Littlejohn were involved in the most in famous crime of the 19th century. In August 1888, the body of a prostitute was discovered in a Whitechapel gutter, her throat slit and her body mutilated. It was the first of five killings believed to have been perpetrated by Jack the Ripper. When the fifth and final victim, Mary Kelly, was found, her ears, nose and organs had been removed and arranged neatly around her body, with her heart on the pillow. These crimes outraged and terrified London. In its haste to fi nd the serial killer, Scotland Yard enlisted the help of eminent detectives from around the UK, including Bell and Littlejohn.

Each carried out his own investigation. ‘There were two of us in the hunt,’ wrote Bell, ‘and in the same way as two men set out to fi nd a golf ball in the rough, when two men set out to investigate a crime mystery, it is where their researches intersect that we have a result.’ The suspects included a Polish barber, a Russian physician, an American sailor and an English doctor – who was found floating in the Thames after the last murder.

Littlejohn and Bell each wrote the name of the man they suspected on a strip of paper, placed this in an envelope and exchanged them. Both had written the same name. Unfortunately there is no record of what this was, and a week later the murders ceased.

Joseph Bell died on 4 October 1911, aged 73. His funeral, at Edinburgh’s Dean Cemetery, was one of the largest ever seen in the city, a testament to the popularity of this extraordinary man.

According to Conan Doyle (well known for his love of the supernatural), Bell made one final appearance: at a séance. The dead man’s daughter rubbished such claims, stating that if her father were going to come back before anybody, ‘I am most sure it would be me.’

Since he first appeared, in 1887’s A Study in Scarlet, Sherlock Holmes has proved enduringly popular. Robert Downey Jr has starred as the detective, while Benedict Cumberbatch’s modern-day version on the BBC won a number of awards. But the character, of course, would not have existed at all without the real-life deductive powers of the remarkable Dr Joe Bell.

This feature originally appeared in 2016.

TAGS