The Scot who was left out in the cold

The ill-fated Arctic voyage of HMCS Karluk was the first in a series of tragedies to befall Glaswegian adventurer William Laird McKinlay and his family.

Scots teacher McKinlay longed for adventure. At just 5ft 4in, ‘Wee Mac’ had been a frail child, but as an adult he became synonymous with the phrase ‘a real survivor’.

In April 1913, while teaching science at Shawlands Academy in Glasgow, McKinlay, then 24, was offered a place on the prestigious Canadian Arctic Expedition that promised ‘no salary, but all expenses paid’.

McKinlay had been helping his friend, Scots explorer Dr WS Bruce, collate information about the Scottish Antarctic Expedition of 1902-4 and jumped at the chance to go on his own polar adventure.

But of the ill-fated 1913-16 expedition, barely a soul knows of the existence of McKinlay on his home ground.

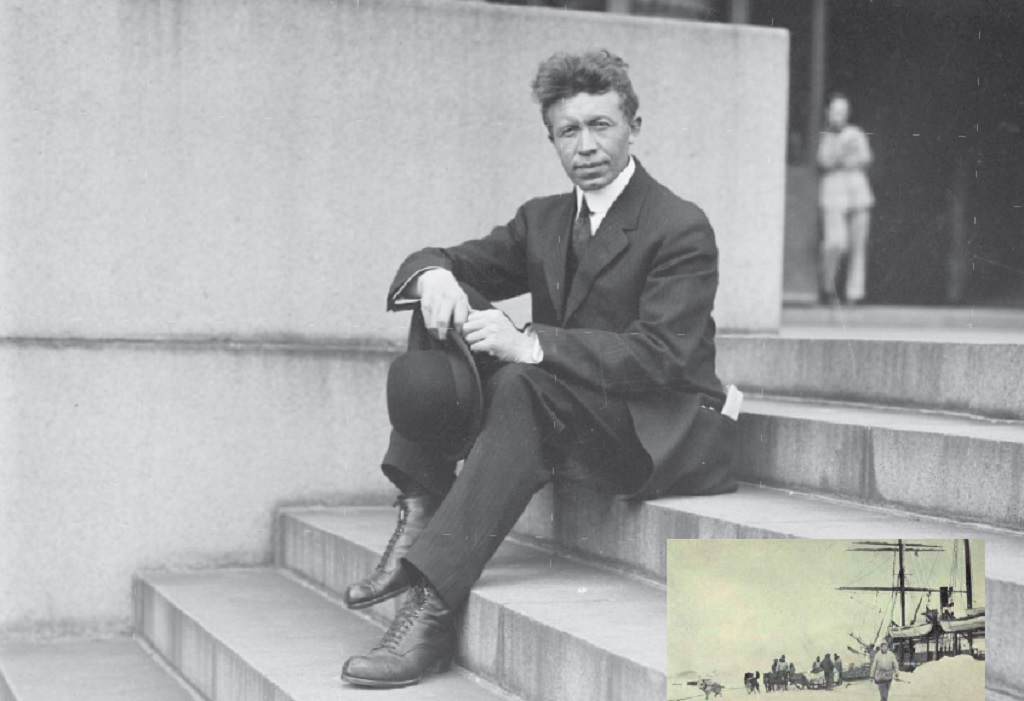

William Laird McKinlay on the right smoking his pipe

McKinlay left his home at 69 Montrose Street, Clydebank, and like so many Scots adventurers before him, sailed from Greenock, with several family members in tow to wave him off on the Atlantic voyage to Canada to join the rest of the expedition party.

He was armed with a copy of the Bible, a leaving gift which bore an inscription inside from the 121st Psalm: I will lift up mine eyes to the hills … my help cometh from the Lord. These words would offer succour to the religious McKinlay as he battled the barren mass of the Arctic.

Reaching Canada, he signed on as magnetician and meteorologist for the expedition led by Vilhjalmur Stefansson, a Canadian anthropologist of Icelandic descent who believed there was an uncharted continent in the Arctic.

The thirty-strong party, which included three other Scots, set sail aboard HMCS Karluk, a 29-year-old wooden whaler which, according to skipper Bob Bartlett, had a weak hull and despite having overwintered on six whaling expeditions could never break through the ice when required.

The Karluk became stuck in the ice

Stefansson picked up the Karluk at the bargain price of $10,000; her engine was nothing more than ‘an old coffee pot’ according to Inveraray-born chief engineer John Munro.

On 17 June, the day of sailing, however, McKinlay’s heart was full of the joys. ‘Whatever hardships the future might hold, I felt supremely glad.’

These emotions were to be tested by a shipwreck and death, while leader Stefansson was regarded as a heartless, vainglorious and hugely ambitious individual. The first thunderbolt struck in August when the Karluk became lodged in ice. As blizzards enveloped them, the men tried, mostly unsuccessfully, to hunt for seal, so they might preserve their rations.

The following month Stefansson and five others left to ‘hunt for caribou’, but never returned. On board The Karluk temperatures could fall to as low as minus 60°C. ‘Condensation froze and we slept in a miniature ice palace, crystals sparkling in the light, gleaming icicles hanging from the deck above,’ said McKinlay.

The Karluk drifted for four months before it was finally crushed and sank. The 25 survivors of the wreck – 13 crew, six scientists, five Inuit, one passenger, 16 sled dogs and a cat – set off across the ice for Wrangel Island, a remote spot in the Arctic Ocean. Eight died on the ice, including legendary Scottish explorer, Dr Alistair Forbes Mackay, who had been on the Antarctic expedition in 1908-9 with Ernest Shackleton and, along with Douglas Mawson and Professor Edgeworth David, became the first human to reach the South Magnetic Pole in 1909.

Expedition leader Vilhjalmur Stefansson (inset) Stefansson abandoning the ship

In March 1914, Stefansson had wired the New York Times, to which he had sold his story, that he was sure the Karluk and its men were safe. In reality, skipper Bob Bartlett had struck out, accompanied by an Inuit man, to find a rescue ship. This involved a 600-mile trek by dogsled to Siberia, then on to the Bering Strait where they found a ship that transported them a further 100 miles to Alaska. There Bartlett persuaded the skipper of another ship, The Bear, to take him to Wrangel Island.

During the months Bartlett was gone, despair descended on the group, which included the wife of another of the Inuits, and their daughters, Helen 11, and Mugpi, who was just three. On 25 June, as starvation set in, the crew’s fireman George Breddy apparently shot himself with his revolver.

The reason was given as accidental and later revised as possible suicide, but it has subsequently been put forward that another crewman, Robert Williamson, pulled the trigger and murdered Breddy.

Before The Bear could reach Wrangel, the survivors were picked up by another vessel, Canadian schooner King and Winge, in September 1914 and eventually reunited with Bartlett – eight months after the Karluk sank.

Three more had died by then, two from a mystery illness, later found to be the kidney disorder nephritis, caused by an over reliance on their diet of high protein pemmican – dried powdered meat, animal fat and berries. There were 14 survivors, including the two children; the youngest, Mugpi, who lived to 97, was to become the last survivor of the ill-fated voyage.

McKinlay referred to their so-called leader, Stefansson, as a ‘consummate liar and cheat’, adding, ‘There was for me only one real hero, Bob Bartlett, honest, fearless, reliable.’

Wee Mac was also a hero. As the survivors suffered from near-starvation, snow blindness, frostbite and gangrene, his religious beliefs kept him from going under and ensured he did his best to help the others and keep up morale.

The expedition sleds

Eventually returning to Scotland, he joined up for the Great War. He was invalided out after serving on the Western Front as a lieutenant with the 51st Highland Division having been seriously wounded in 1917 – thereafter walking with a limp.

‘Not all the horrors of the Western Front, not the rubble of Arras, not the hell of Ypres, nor all the mud of Flanders leading to Passchendaele could blot out the memories of that year in the Arctic,’ he would later recall.

Later he married and became headmaster at Greenock’s Mount Junior Secondary. During the Blitz, his heroic qualities again came to the fore. McKinlay co-ordinated aid for many of those left homeless, and helped feed and clothe victims as well as fi nding them temporary housing. He was made an MBE in 1956 for his youth work as a ounder member of the Scottish Leadership Association. His later life was spent in Kirklee in Glasgow’s West End.

McKinlay died in 1983 aged 94, leaving two daughters, actress Patricia Craig, who was tragically killed in a car crash on the A9 two years later, and Ann Baillie Scott, whose demise 20 years later became the fi nal dreadful piece of the troubled family history.

Ann’s own daughter, Jennifer Byrd, killed her elderly mother by strangling her with a scarf. She had recently returned to Kilmacolm from the US following a divorce and had hoped to hasten her inheritance, but was instead she was jailed following conviction for culpable homicide.

In a cruel twist of fate, Jennifer was the granddaughter who in the early 1970s, while rummaging through her grandfather’s things, had come across his Arctic notes and persuaded him to publish them.

(This feature was originally published in 2016)

TAGS