From Joe Rosenthal’s striking image of the moment the American flag was raised on Iwo Jima – the most reproduced image of all time – to Nick Ut’s heart-wrenching Pulitzer-winning photograph of burning children fleeing a napalm bomb in Vietnam, photographs of war represent some of the most memorable images of modern times.

Among the first to capture images of conflict was pioneering Scotsman Alexander Gardner, who paved the way for photojournalism as we know it.

Throughout the American Civil War, Gardner would make history with his camera, capturing death and destruction on the battle fields as well as taking evocative portraits of President Abraham Lincoln.

‘Alexander Gardner stands out as the premier photographic documentarian of that conflict,’ says Bob Zeller, president of the Center for Civil War Photography in Ohio.

‘His war images, as well as his photographs of the American West, place him among the premier photographers of the 19th century.’

Gardner was born in Paisley on 17 October 1821. As a young boy, his mother Jean encouraged his studies, and he excelled in science before leaving school at the age of 14 to become an apprentice jeweller.

Working in that trade before switching to finance, then journalism, Gardner travelled to the United States with his brother James in 1850, establishing a co-operative community in Iowa.

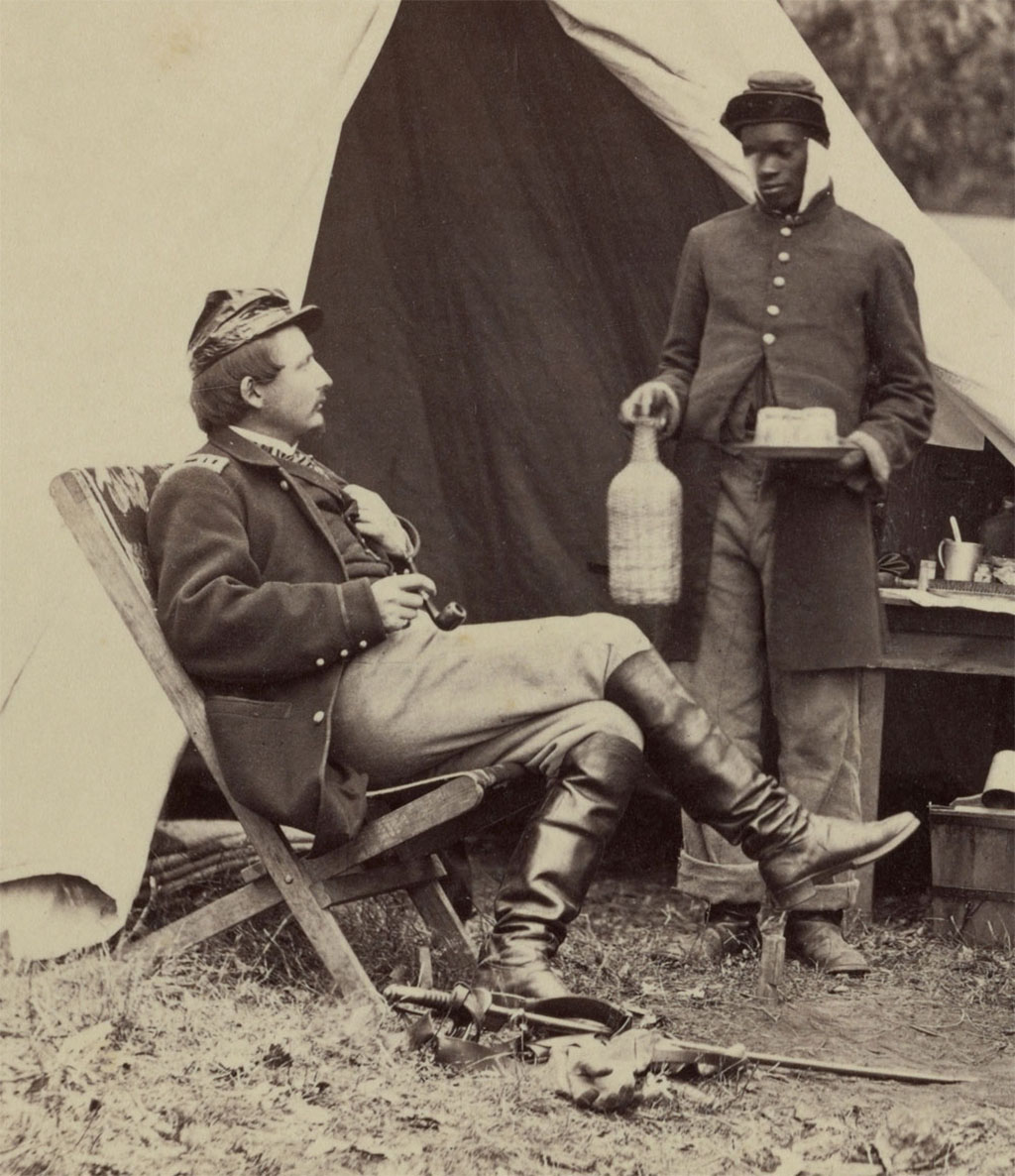

A cavalry orderly at Antietam

Returning to Scotland to raise money, Gardner acquired the Glasgow Sentinel newspaper; in it he wrote editorials promoting social reform, and it quickly became one of the largest-selling newspapers in the city.

In May 1851 he visited the Great Exhibition in London’s Hyde Park – a trip that would change the course of his life. So impressed was he with the work of American photographer Matthew Brady that he began to experiment with the new technology himself, taking a back seat at the newspaper to develop his craft.

In 1856, Gardner headed back to the US, this time for good. With much of the colony in Iowa falling victim to tuberculosis, he decided to stay in New York and contacted Brady looking for work. The 35-year-old Scot was hired and worked in Brady’s prestigious studio and portrait gallery at 359 Broadway.

Gardner had been in the city for almost four years when a little-known lawyer from Illinois arrived to give a manifesto speech.

The man in question, Abraham Lincoln, had his photograph taken by the Brady studio later that day. Elected in 1860, the picture went on to establish the identity of America’s next president.

Lincoln’s anti-slavery stance appealed to Gardner, who had previously observed in the Sentinel that slavery was ‘a stain on the escutcheon of the otherwise freest country in the world’.

An officer and slave, in an image taken by Scotsman Alexander Gardner, who loathed slavery

Not all of America agreed, especially the southern states, and Civil War seemed inevitable. Washington would be at the centre of the war, and a Brady franchise was set up in the capital. Sent to manage the new gallery, it was Gardner who photographed a deeply troubled Lincoln there in February 1861.

Having ordered special cameras that took four photographs at once, Gardner shot portraits of many of the uniformed soldiers arriving in the city, who wanted pictures to send home. He also began to recognise the value of photographing in the field.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, he proclaimed himself photographer to the Army of the Potomac and took to the battlefields with a horse-drawn darkroom, armed only with his bulky tripod-mounted camera.

With shutter speeds so slow that subjects had to be still for seconds at a time for a picture to succeed, action shots were impossible. Instead, Gardner shot the aftermath of battle.

The pictures he took at Antietam, where 23,000 men were killed or injured in one bloody day in September 1862, were the first images of American dead on a battlefield. They were unlike anything ordinary Americans had ever seen, but Brady displayed the pictures in his New York gallery.

Fascinated and horrified, New Yorkers queued around the block to view the gory images. ‘Mr Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war,’ said the New York Times. ‘If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it.’ Gardner’s name was not mentioned in the review, with the studio owner gaining credit for the shots.

The Westover Landing in 1862

Later that year, the Scotsman set up his own studio in Washington. Gardner returned to the fi eld in July 1863, travelling to Gettysburg where 8,000 men lost their lives. The resulting images are considered classics of war photography, despite proving controversial in recent years when historians discovered that some of the pictures had been staged – the same rifle was placed next to various Confederate corpses and one body was seemingly moved to another, more dramatic position.

Today this would be considered highly unethical, but it was pioneering photography in those days; Gardner considered this staging part of the art and there were no rules. Back in Washington, he had a thriving business which was visited by Lincoln on several occasions. Moving away from stiff poses against false backdrops, Gardner was exploring the possibilities of por trait ure and captured a relaxed-looking Lincoln in a series of pictures taken in August 1863.

In a letter following that session, the President wrote, ‘The imperial photograph in which the head leans upon the hand, I regard as the best that I have yet seen.’

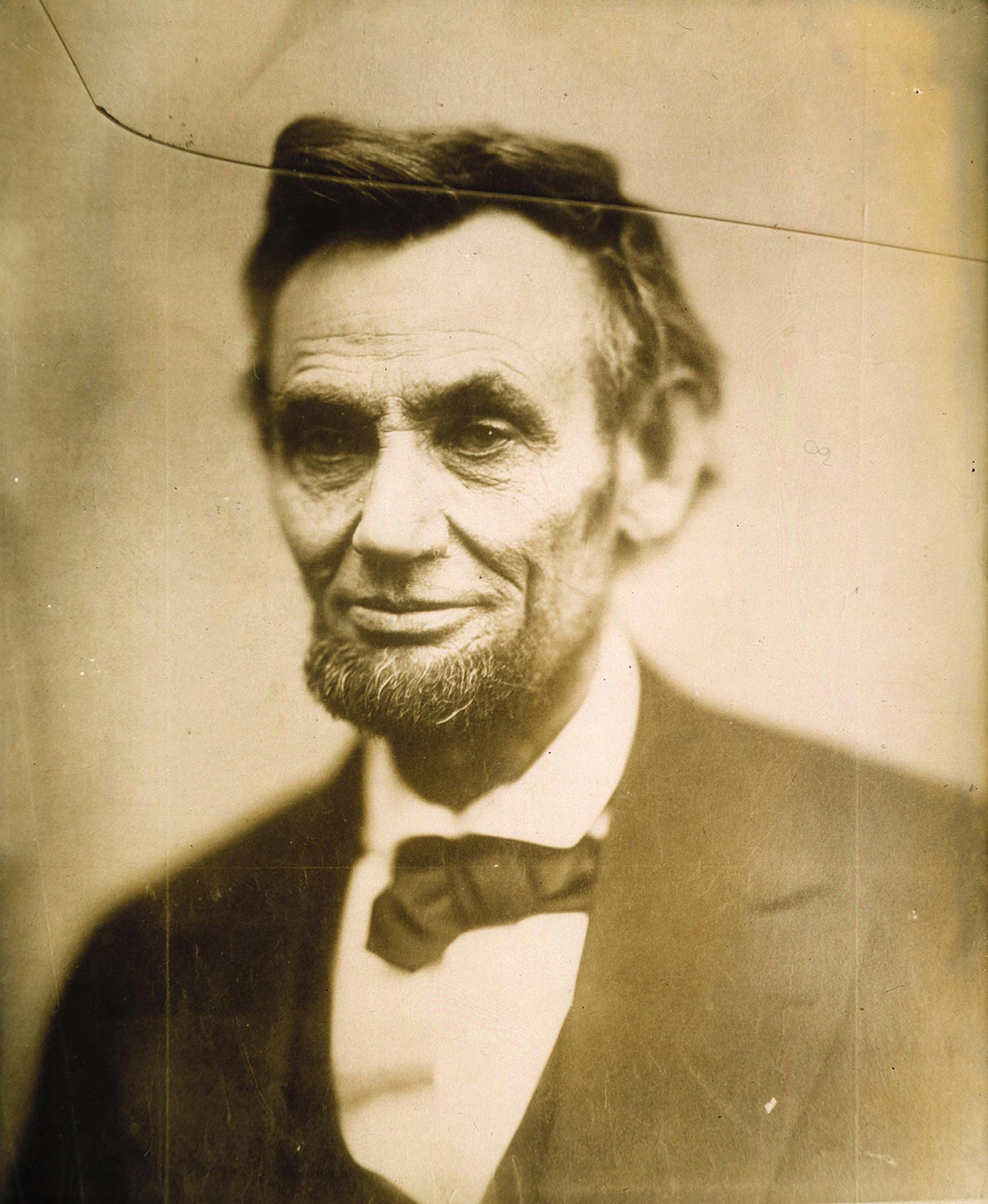

A month before Lincoln’s second inauguration, Gardner shot the famous ‘cracked plate’ portrait, showing the president with a small, compelling smile. Just one print was made before the negative, deemed ruined by the crack, was destroyed. The National Portrait Gallery of America calls it the Mona Lisa of its collection.

The famous cracked plate shot of President Lincoln

The tired-looking president captured in that portrait had just two months left to live; he was assassinated on 15 April 1865 by the actor John Wilkes Booth. It was Gardner’s portrait of Booth that was used on wanted posters – the first time a photograph was utilised in this way. Later, when the conspirators’ were hung, the Scotsman photographed the execution.

Gardner’s gallery continued to prosper and he published a two-volume collection of images he’d taken during the Civil War. In it he wrote, ‘Here are the dreadful details. Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation.’ He then turned his camera towards the building of modern America, travelling west to shoot the new cities and railways.

Laterhe was asked to photograph the Fort Laramie Treaty, which gave the Sioux tribe control over the Black Hills. As well as capturing the peace talks, Gardner took 200 photographs of the Native Americans of the Northern Plains, publishing them as Scenes in the Indian Country. He died in 1882 at the age of 61 and is buried in Glenwood cemetery on Lincoln Road.

To this day we visualise the American Civil War largely through Gardner’s pictures, while Abraham Lincoln’s character is more accessible thanks to the Scot’s portraits which focus on the eyes, offering a glimpse into the soul of America’s great war-time leader.

Gardner saw further than his camera and paved the way for photojournalism as we know it.

TAGS