The talented Mr Crichton – and his sad demise

With a dazzling intellect that won him fame across Europe, coupled with brilliant dancing, riding and duelling skills, there was never a man better named than the Admirable Crichton.

Life can be uneven in the gifts it distributes to people – as evidence of this, one need look no further than the case of James ‘The Admirable’ Crichton, who possessed more than enough ability for ten men.

The child who would become known as The Admirable Crichton was born on 19 August 1560. His father, Robert, was a man of high standing, whose lineage could be traced to a one-time earl of Dumfries.

But young Crichton’s ‘extraordinary endowments of the mind’ would bring him distinction beyond that of mere aristocratic descent, as told by author Thomas Babington Macaulay in his Biographies of Illustrious Men.

Though one account places Crichton’s birth at Clunie Castle in Perthshire, his more likely birthplace was Eliock, near Dumfries.

Wherever he was born, the brilliance within him surfaced early and, at the age of ten, he entered the University of St Andrews. With a multi-faceted mind, and a voracious appetite for its cultivation, he devoted himself to ‘the pursuits of science as well as literature’.

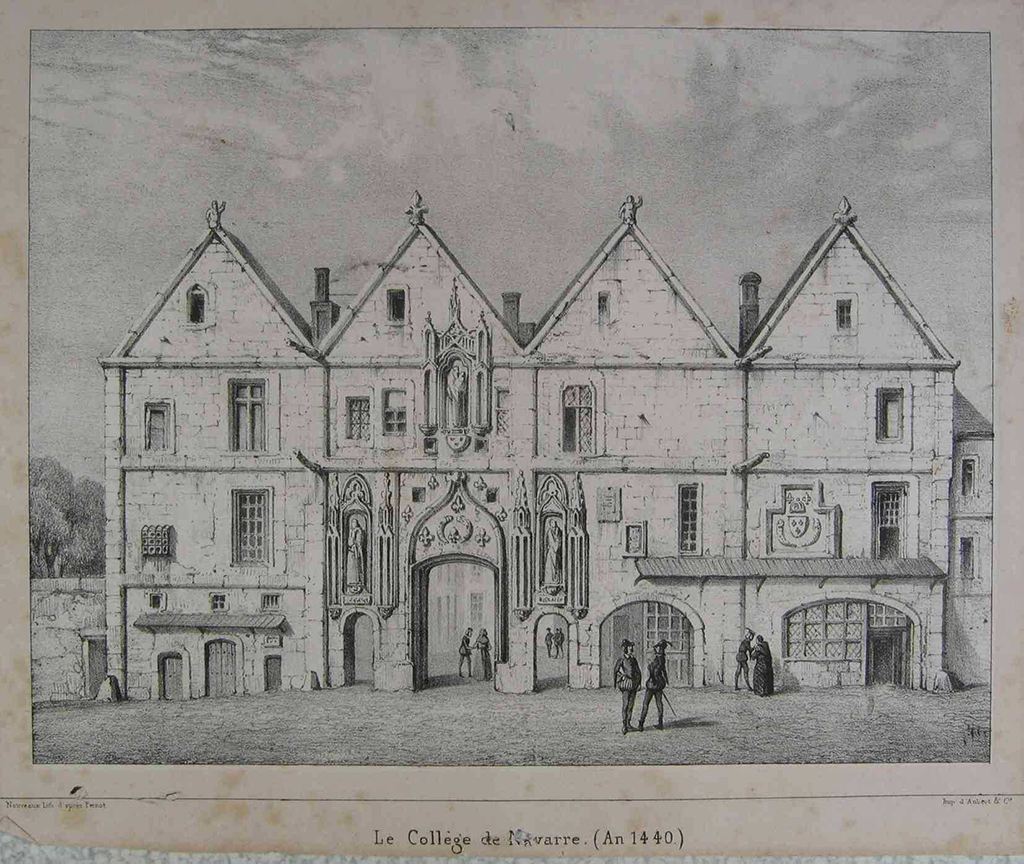

It appears that Crichton left Scotland in 1577, when he headed to the Collège de Navarre in Paris. Once he had settled into this illustrious branch of the University of Paris, he issued a curious challenge.

All prominent scholars in the city were put on alert: young Crichton claimed he could answer any question put to him, no matter how obscure the subject, and, moreover, that such questions could be asked in any of 12 possible languages, ranging from Arabic to Dutch.

The Collège de Navarre, in Paris, where Crichton studied in 1577

Crichton put up notices throughout the city proclaiming that he would ‘answer to what should be propounded to him concerning any science, liberal art, discipline, or faculty, practical or theoritick’.

The young man was undoubtedly putting great pressure on himself. But when the scholarly showdown took place, he ‘acquitted himself with stupendous learning and ability, having for the space of nine hours maintained his ground against the most eminent antagonists in all the faculties’.

He provided flawless answers to questions from a formidable collection of canonists, grammarians, rhetoricians, philosophers and theologians. The Navarre college rector, so impressed by this display of intellect, presented the confirmed prodigy with ‘a diamond ring and a purse full of gold’.

Had he been no more than an enormous brain, Crichton would have been impressive enough, but his accomplishments went far beyond the sphere of the intellect. Among the other activities in which he excelled were dancing, hunting, riding, tossing the pike, swimming and billiards.

He was also ‘highly celebrated for his martial powers’, having attained mastery in the use of the sword and spear. These talents were acquired and refined during the two years he spent fighting in the civil wars of France.

Following his service with the French army, he headed to Italy. In Genoa, he reportedly delivered a Latin address at the election of the senate. At some point during 1580, at the age of 20, he arrived in Venice, where he formed a friendship with Aldus Manutius of the famed publishing family.

Manutius introduced his new friend to many men of arts and letters and Crichton soon became the darling of a Venetian cultural community that was blossoming with the seeds of Renaissance humanism. Producing a memorable effect on almost everyone he met, Crichton’s literary talents were said to have ‘astonished the Italians’.

Not every impression was favourable, as might be imagined. As biographer Macaulay relates: ‘The popular applause that attended such demonstrations of intellectual superiority had too natural a tendency to excite envy.’ The prodigy stirred up further tension when he ‘undertook to refute innumerable errors of Aristotle’.

His next calling point was Padua, where he clashed with several professors from the ancient university there concerning their interpretations of Aristotle.

He also pointed out the fl awed mathematics of several faculty members. As embarrassing as these demonstrations might have been for the professors, they served only to bolster the legend of Crichton. The Scots expat was soon looked upon as ‘one of the wonders of Italy’.

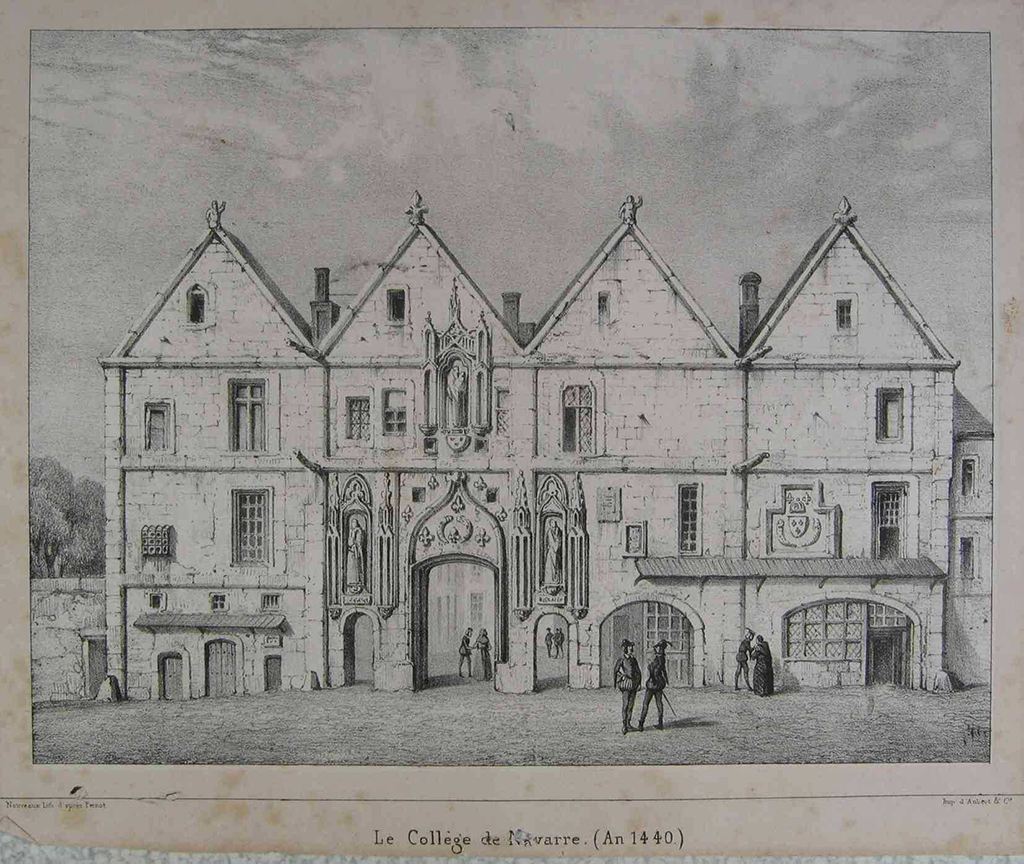

The Duke of Mantua, the former Prince Vincenzo, who murdered Crichton in 1582

Rapier wit Crichton’s clashes were not always of the intellectual sort. Soon after relocating to Mantua, he engaged in a duel with a ‘fierce Italian gentleman, who had recently slain three antagonists’. A tested brawler and scholar, Crichton expertly wielded his sabre and ultimately ‘pierced the belly’ of this much feared swordsman. In a strange example of higher learning, Crichton observed that marks of his adversary’s wounds resembled an ‘isosceles triangle’.

Though this would not be Crichton’s last physical altercation, there are no more reports of any showdowns with irate Italians. Perhaps he had lost his taste for argument, as he soon entered the council of the Duke of Mantua, who sought the young man’s advice on how to best fortify his palace. Crichton also became the personal tutor of the Duke’s son, Prince Vincenzo.

As with everything he did, Crichton excelled in this new role. But the deep admiration he won from the Duke aroused an equally intense jealousy in Prince Vincenzo. Not surprisingly, this envy only grew when Crichton became the lover of Vincenzo’s former mistress.

On the night of 3 July 1582, as Crichton, ‘with his lute in hand’, returned from a visit to his mistress, he was set upon by three masked men on the streets of Mantua. Fighting back, he dropped the lute, reached for his sword and proceeded to defend him self with great skill. Having made short work of the first two attackers, he turned his attention to the third man, who promptly unmasked himself. It was Prince Vincenzo.

The story goes that, on seeing his master’s son before him, Crichton, despite the danger of his situation, put down his sword, then ‘fell upon his knees and entreated forgiveness’. It was an honourable gesture but hardly a wise one.

The Prince instantly took advantage of the situation, seizing Crichton’s sword and stabbing him though the heart. Death was as immediate as it was violent.

And so was ‘terminated the mortal existence of one of the most remarkable persons of the era to which he belonged’. Crichton was all of 21 years of age.

Macaulay reflects on how this untimely demise prevented the world from knowing what might have been a major cultural figure in the course of history. Such an early death instead consigned Crichton to the status of a curious, tragic footnote.

Though prodigies continue to live among us, the days of the polymath have been left far behind. In this increasingly complex world, there is vastly more information out there and some of the world’s brightest minds now devote entire careers to elucidating the smallest fraction of knowledge.

It’s a near certainty we’ll never see another Admirable Crichton.

- This feature was originally published in 2014.

TAGS