The Titanic and the ruined Fife palace

The fate of Leslie House in Fife, once the seat of the Earls of Rothes, is in the balance. The A-listed house, which was known as the Palace of Rothes, stands burntout and bereft.

In its heyday it resembled Holyrood Palace and was described by Daniel Defoe as ‘the glory of the whole province of Fife’. Today, as developers prowl and councillors debate its future, I think of the woman who once lived there at the start of the twentieth century and what she endured to get back to her home at Leslie.

My great-grandmother, Noël, Countess of Rothes, became chatelaine of Leslie House when her husband, Norman Evelyn, the 19th Earl of Rothes, inherited it in 1904. Between then and 1919 Noël oversaw the large household staff there, so she knew much about encouraging, managing and gently persuading people.

She also knew about boats, because she and my great-grandfather owned a yacht. Both of these seemingly unrelated factors were to play an unlikely role in saving her life.

Leslie House in Fife, pictured in its heyday

In April 1912 Noël left her two young sons at Leslie and travelled south with her ladies’ maid, Roberta Maioni, to Southampton. From there they took a steamship across the Atlantic accompanied by my great-grandfather’s cousin, Gladys Cherry.

But the steamship they sailed on was the RMS Titanic and when it hit an iceberg on the fateful night of 14 April Noël and Gladys were ordered into Lifeboat Number 8. Before she did so, Noël promised an 18-year-old Spaniard that she would take care of his 17-year-old wife – the couple had been on their honeymoon. In the lifeboat Noël did her best to comfort all of those on board, including the young Spanish woman.

There were 35 passengers in their lifeboat and when Able Seaman Thomas Jones, the only seaman on board, saw the determined way Noël coped with the terrifi ed passengers, he knew, as he put it, that she was ‘more of a man than any we had on board’. Noël taught the other women to row and when Jones asked her to take the tiller, she did. Noël was one of the few who agreed with Jones that they must turn back to pick up more passengers when it was clear that Titanic was sinking.

Jones said he would rather drown with those left in the water than leave without them, but neither he nor Noël could persuade a majority to return so they rowed away while calls for help from the desperate people left behind echoed across the water. Afterwards Noël wrote, ‘Their fearful cries will never go out of my head.’

Noel, Countess of Rothes

It was a long, cold, terrifying night. For those who died, and for their families and friends, it was an irredeemable tragedy. For Noël, Gladys and Able Seaman Jones, it was a night of selfl ess commitment to the survivors.

One thing Noël and Gladys thought would help was singing: it sounds trivial, but singing comforted the passengers and distracted them from the fear that they might never be rescued.

As they rowed past icebergs that looked uncannily like huge ships beneath a sky fi lled with stars – ‘As if,’ Lawrence Beesley wrote in The Loss of the Titanic, ‘the stars were flashing messages to each other about the calamity that was unfolding beneath them’ – the passengers in Lifeboat Number 8 sang their hearts out. They were still singing when the lights of RMS Carpathia, the ship that came to their rescue, shone out over the horizon five long hours after they’d left Titanic.

Several weeks later Noël gave Jones an engraved silver fob watch, to thank him for all he’d done, and he made a wooden plaque for her, set with one of the bronze 8s he’d taken from the prow of their lifeboat. He told her it was for her courage ‘under so heart rending circumstances’.

The two wrote to each other until 1956, when Noël died. It was their letters, and letters between her and the young Spanish widow, that my grandfather (the elder of the two sons Noël left behind at Leslie in April 1912) found after she died, letters that told of friendships forged and hope renewed after that fateful night.

Noël didn’t have long to recover from her ordeal in the North Atlantic. Tensions were rising across Europe and war was on the horizon. She and Norman didn’t know then that economic pressures after the First World War would mean they would have to sell up. They didn’t know that they would be the last generation of Leslies to bring up their children at Leslie House.

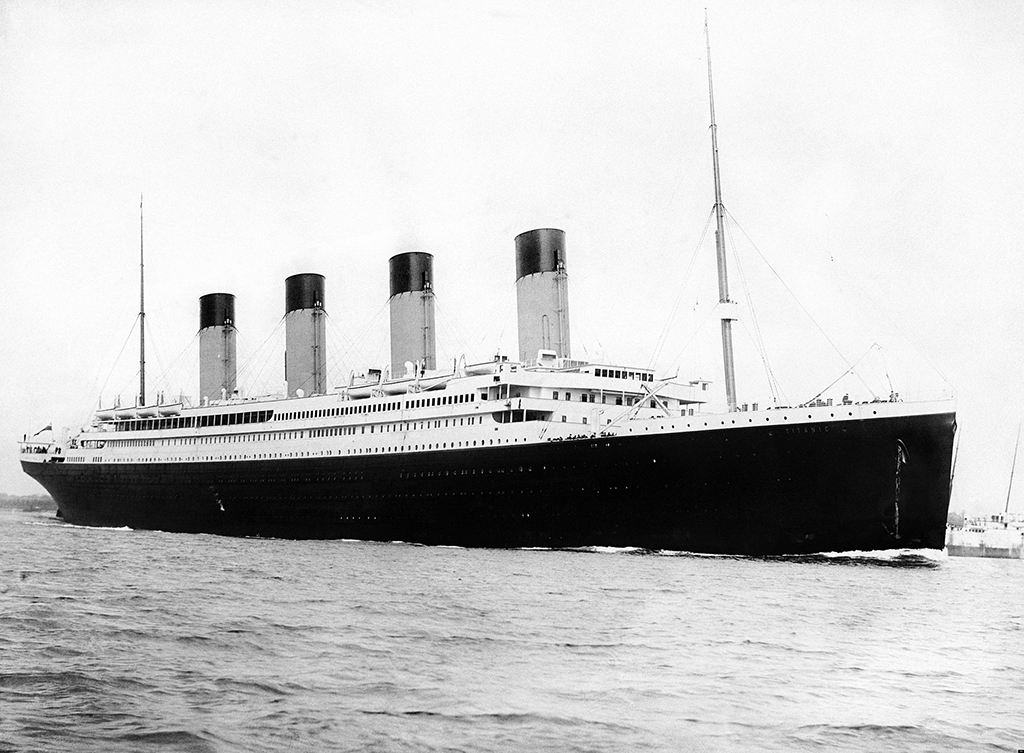

The RMS Titanic

The house my great-grandparents had inherited was the surviving west wing of a much larger house, built in the 1660s for John, 7th Earl and 1st Duke of Rothes. That house, the one that had so impressed Daniel Defoe, was almost destroyed by fire in December 1763.

Enough of the west wing survived to make rebuilding possible; some of the rubble was even used to build the still-standing southern terraces. But in 1919, in the aftermath of war, my great-grandparents had no choice but to sell their home to Sir Robert Spencer Nairn. He in turn gave it to the Church of Scotland in 1952, who made it a residential care home.

Leslie House, or at least what remains of it, is currently owned by Sundial Properties. The development company bought it in 2005, intending to convert it into 17 fl ats. It also sold the surrounding land to Muir Homes, who hoped to build 12 new houses on it. Planning permission was granted in 2008, but only on the condition that any profits from sales would be used to fund the restoration of Leslie House. Within a year, however, a devastating fire tore through the ancient building and the whole project was put on hold.

A second planning application was lodged by Muir Homes, this time to build 29 houses, but minus the enabling development clause since the refurbishment of Leslie House was no longer germane to the project. Several objections to this were lodged with Fife Council and, on 26 August 2015, the application was turned down. Local people, fearing the historic building has been once again left in limbo, have urged the council to find some way forward.

Leslie House,pictured in, 2008

I had to find my own way forward when I began writing a novel about my greatgrandmother’s Titanic experience. The ship’s story has, of course, been dramatically told many times, and it was my intention to weave it into an account of a love affair – but I struggled to bring it to life. In a despairing last attempt to make it work, I sent the manuscript to the Literary Consultancy for assessment.

Melissa Marshall, one of the readers there, wrote this: ‘At the novel’s heart is a complicated love story. But then it steers hugely off course with the Titanic episode. This is a massive story in itself and rather dilutes the impact, importance and credence of the main storyline, which is the story of unrequited love. I think the Titanic story is an entirely different novel altogether and I would urge you to consider removing it.’

You might think my despair would be increased when I read those words but TLC’s assessment showed me I’d been trying to combine two stories, one factual and one fictional, without realising that in order to do that well (it was my first historical novel), the personal stories must be the colourful filters through which the facts are glimpsed, not the other way round. So I razed the original edifice of my two-story novel and rebuilt it, and it was then that a single story began to sing, a story that, under the title The Dance of Love, found a publisher.

Angela Young (Photo: Lumley Pictures)

And so, because it’s always possible to find hope among the ashes, to start again when all seems lost, even to sing in the face of fear and despair, I hope that an innovative alternative use for Leslie House – which stands bravely awaiting its second rescue and rebirth – will be found.

At a meeting chaired by Fife’s Councillor Fiona Grant, Chair of the Glenrothes Area Committee, on 16 September 2015, a meeting to which Sundial Properties, Historic Scotland and officers of Fife Council attended, they agreed to produce a development brief for exactly that purpose.

Angela Young’s novel, The Dance of Love, which was inspired by the life and times of her greatgrandmother, Noël Rothes, is available HERE priced £8.99.

(This feature was originally published in 2015)

TAGS