Olympian Ian Stark is Scotland’s main eventer

In a long and distinguished career in the saddle, Ian Stark won medals at three Olympic Games and enjoyed a host of other sporting triumphs. And it all began in the Borders, where he had his first pony ride at the age of 10.

I grew up in Galashiels in the Borders, the youngest of three siblings. When I was ten I became interested in horses.

My sister had started riding at Will Boyle’s Ladhope stables in Galashiels and had got a bit frightened, so I went with her one day. I went for an hour’s ride – I was led up and down a drive doing a rising trot and then we went up round the hill and at the first field we took off and galloped. I thought, ‘yikes, I’m going to die!’ But I survived and I loved it. I was hooked.

From the age of 11 I rode in the local Braw Lads Gathering and the other Border festivals. After a few years Will Boyle gave up hiring out horses and did a lot more buying and selling, so when I was about 15 to 17, I was there all the time, breaking horses and producing horses for him to sell.

I left school at 18 and my friend Jackie Rodger and I started buying and selling horses ourselves – and I started competing. I also started working for the Department for Health and Social Security. I worked there for ten years, but spent all my spare time with the horses.

A very young Ian and Black Magic at Selkirk Common Riding Gymkhana (Photo: Ian Stark)

I did a lot of showjumping as a kid, but eventing and riding cross-country were what I really wanted to do. Jackie had a hunter called Glen Moidart and I rode him in my first event.

When I was 25, I got married to Jenny and we moved to Ashkirk, just south of Selkirk. Three years later we had two children, Stephanie and Tim. I was still working at the DHSS, but Jenny had so much to do, looking after the kids, plus my two horses. I was riding in the morning, charging back at lunchtime, then trying to get home before dark to ride more. It was mad. I complained so much that one day Jenny said, ‘Just quit the job!’ I thought she was joking but she wasn’t, so I did. The offi ce thought it was just a formality, because I was never there anyway – those flexible working hours had become very flexible in my case.

In those early years we made a living breaking and schooling horses, and we both taught. It was around that time that we were given two six-year-old horses, Sir Wattie and Oxford Blue, for me to compete on. I knew Sir Wattie well – he belonged to Dame Jean Maxwell-Scott of Abbotsford House and Mrs Susan Luczyc-Wyhowska, and I’d been riding him since he was four. Oxford Blue was from Inverurie and was owned and bred by Liz Davidson.

Within the next year, I had won Bramham, a three-day event in Yorkshire, on Sir Wattie, and I was third on Oxford Blue. I took Sir Wattie to a big three-day event in Germany and was second, then took Oxford Blue to a big one in Holland and he was seventh, so both were put on the long list for the upcoming Olympics in Los Angeles. Jenny and I just sort of laughed at that and thought, ‘that’s very nice,’ because I’d never ridden at four-star level – the level of elite international competition.

Then, in 1984, aged 30, I had my first Badminton Horse Trials – a four-star event.

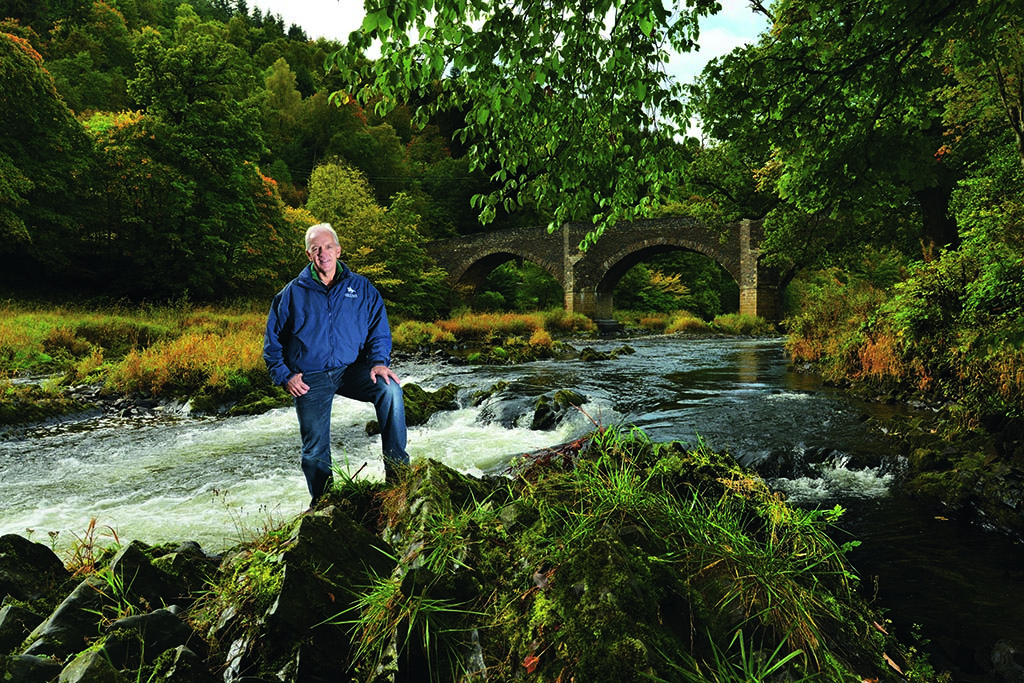

Ian Stark stands by the River Tweed at Yair Bridge (Photo: Angus Blackburn)

The horses ended up third and sixth. They were only eight years old, so very young. Most horses competing at that level would be ten at least. But they were good horses and I got on with them and it worked.

After Badminton, David Stevenson, who owned the Edinburgh Woollen Mill, got involved. We’d known him and his wife Alix for quite a long time and we shared the same accountant. David said to our accountant one day, ‘What are Ian and Jenny doing to survive – how are they managing?’ And he said, ‘Well, they’re struggling.’ It was true – when I was not competing at the big levels, I had time to school a lot of horses and make quite a lot of money, but as I got more and more busy competing, I had less time to make money and we were spending at a vast rate.

David realised that and he sponsored me for almost nine years. He was brilliant. He bought me a new truck, bought me all my horses. All my prize money went to pay him back, so that when the sponsorship contract finished after nine years, I’d paid for the horses with the prize money, so they were all ours and we didn’t lose them. This was a part of the new contract that David insisted on, much to my relief and appreciation.

When I was shortlisted for the Los Angeles Olympics, we had to go down to a team training session at Wylye in Wiltshire, and then to Castle Ashby in Northamptonshire. That was our final trial and we had to compete. Both horses went well, I was interviewed, and then they announced that I had made the team and would be going to the Games. Well, you could have knocked us over, really.

Between competing, I was still training. We had students from all over the world who were trying to get to the top. They would come and stay with the horses and I would teach them.

They would travel with us as well, because my contract meant I had to have seven horses on the road competing at any one time. In hindsight we were pushing ourselves too much – we hardly had time to breathe, but we loved it.

Ian Stark likes to spend relaxing evenings eating out in Melrose (Photo: Angus Blackburn)

I somehow also managed to fit in 12 years of point to point. I didn’t really enjoy it. I was very happy galloping cross-country on my own but when you’re in a race, in the middle of a group of 15 other horses and you can’t always see the fence, I didn’t like that. Eventually I just trained racehorses and we had quite a bit of success with that – point to point and hunter chasers.

People say I’ve had about five retirements so far. I gave up the teams after 2000 and I did my last four-star competition in 2007, in Kentucky. That was very emotional. The British team brought me this massive card signed by all the riders from the event and I was then taken into the ring and interviewed. It was very special. But I was already 54, so it was time for me. I think I’d done enough and it was time to do something else.

It was about then that I started designing cross-country courses. After the Edinburgh Woollen Mill, my main owners became the Duchess of Devonshire and Lady Vestey. The Duchess had Chatsworth House, and she and the man who designed the cross-country course there, Mike Hetherington-Smith (who was probably the best in the world at that point) suggested that I design the novice track.

Designing had never entered my head when I’d been competing as we were so busy, but I said, ‘Okay, I’ll have a go, but if I’m absolutely terrible, you must just tell me and I’ll go and do something else.’

I actually really liked it and luckily I had a feel for it, so they fast-tracked me through the British system and on to the international system, so that within a few years I was designing at quite high levels.

I’d love to have the opportunity to design the course for a four-star event, but it might never happen – there are only two four-star courses in the UK and, along with the Olympics and the World Equestrian Games, only six four-star competitions. You have to wait to be invited to design at that level. But I did the European Championships this year and I’m on the longlist for Tokyo in 2020.

Most of the competitors think I design like I used to ride. Frank Weldon, who designed all my Badmintons, is my design hero. He used to go round the world looking at events and pick up ideas to bring to Badminton, only making them bigger and scarier and better. I liked that. I use a lot of big, terrifying, bold, galloping-type fences. I love to terrify the riders. As long as the horses understand the question, I’m happy.

In 2009 I had a brain haemorrhage. It was a huge scare – more for Jenny and the kids than it was for me. I had the headache and called 999 and they came and rescued me. I was put into an induced coma. We’d always said that if I was injured, somebody would have to pull the plug. Jenny tells me that the first thing I said when I came round was, ‘Are you here to pull the plug?’ It was obviously working away in my head.

Ian Stark riding Sir Wattie at Badminton in 1988

A scare like that definitely makes a difference to how you feel about life but otherwise it didn’t affect me much – after six weeks I was riding again and had entered an advanced event. It caused a bit of panic with the British Eventing officials but I was okay. The only thing that I ever worried about was falling off for the first time and how my head was going to be, but I don’t think the haemorrhage affected my attitude to riding or competing. I’ve always felt that if my time is up, my time is up. What I’ve dreaded far more is being left incapable of making decisions and looking after myself.

I got my pilot’s licence in 2001 and did my helicopter test three or four years later. I’d use it to fly up and down the country for meetings or I’d quite often hire a plane and fly myself to Ireland, land in a field, design a course, then take off again. It was brilliant. I’m not very good with heights so I have to challenge myself. I did some parachute jumping to see if I could kill or cure it, and it helped me.

I have spent my entire career travelling south and abroad to compete and up to Gleneagles, Ayrshire or Glasgow in the winter to showjump because there was nothing locally. Jenny’s mother owned Dryden, a little school which you could use to compete to a certain level, but it was limited so we set up our own equestrian centre at Greenhill Farm near Selkirk.

I had been thinking about backing off and semi-retiring but Jenny really wanted to give it a go. Anyway, the Ian Stark Equestrian Centre has been running for over two years now and has been a huge success. We have an indoor and an outdoor arena, plus training facilities.

We want cross-country fences and eventually we will have competitions. We have the riding school, with 30 to 40 ponies. We also hold Riding for the Disabled classes, host training for Borders College students, and we’ve also got vaulting and dressage. Hawick rugby club uses the indoor school in the winter to train.

We hope to open the farm up more. It’s a hill farm which belonged to Jenny’s family for about 60 years, but these days it’s hard to make a living from just farming so you need to diversify. We get a lot of families coming up here walking, so we plan to open up the cafe.

Our son Tim, who does all the tractor work and fencing, would like to get some old Land Rovers to hire out for off-road driving and to offer quad biking. The centre is actually helping the local economy because of the number of people who come to us stay in the local B&Bs, and visit the shops and restaurants.

Our daughter Stephanie does teaching clinics for us and helps with the marketing, but she’s pretty busy. She has a livery yard for horses, runs marquee company Best Intent with her husband, and has two young kids.

The Ian Stark Equestrian Centre in Selkirk (Photo: Angus Blackburn)

Jenny is the one who keeps the centre going, as I’m in London quite a lot. I do some stewarding work for the British Horseracing Authority, so I’m there every two or three weeks listening to hearings. It’s totally full-on. I also do a little commentating for the BBC – Badminton and Burghley and whatever other championships are on.

When I’m home, which is not often, I like to relax with Jenny and collapse in a heap in front of the telly. If I have time, I go out with the hunt. I’m field master for the Buccleuch Hunt. It’s just great fun to get out and gallop around the countryside. It’s brilliant for the young event horses – they learn all about mud and jumping anything and everything. That’s why I always hunted, really – to get the young horses out.

And if Jenny and I go out for a meal, we often go to Melrose, to The Townhouse, Marmions or Monte Casino. The Townhouse is my favourite – it’s relaxing, has good food and it’s not noisy. I get invited to all sorts of things, all the time, but I turn most of them down. I used to go to everything – I was a real party animal. I’d be all over the country at parties and functions.

Now I enjoy being in the Borders. For about 15 years we spent so much time in Gloucestershire that I felt it would make sense to move there permanently – but then, when we’d come back up, it was a relief to be home. It eventually got to the point where we never wanted to leave the Borders again. For me, it’s all about the countryside and the quality of life up here.

I have been very lucky in life and in my career. Being inducted into the Scottish Hall of Fame and the award from the British Horse Society were very special, but being awarded the MBE in 1989 and the OBE in 2000 – that was a huge honour.

Everyone says OBE stands for Other Buggers’ Efforts, so really, Jenny got that one.

(This feature was originally published in 2015)

TAGS