The life of Game of Thrones and Still Game star Clive Russell

His imposing physique often leads to the Game of Thrones actor being cast as a warrior, but it’s on the beaches of his home in Fife that Clive Russell feels closest to the wild.

I was brought up by the sea and I have returned to the east coast of Scotland. It is life-affirming and elemental.

I was born in Hampshire in 1945, but the family moved up to Fife when my father was demobbed from the army. He was a pilot in coastal command flying Liberators and Lancasters. Like a lot of men who went to war, he didn’t talk about it much. He was badly injured, with shrapnel in his knee. I have lots of photos of my parents at that time and their old uniforms.

As a boy, I would often think, could I do that? I always imagined I would be terrified. But then people of that generation were scared and they got on with it. They were just ordinary boys like us. If you have to do something, you do it. The good thing is that when you come out of the war in your early twenties, you have the whole world ahead of you. It was a time of great optimism. My father was a chiropodist in Leven, working his way up from messenger boy to director of the shoe shop. I had one sister who is ten years younger than me and is now a retired teacher in Fife. We were an ordinary middle-class family.

We lived in a street by the shore, so my life has always been about the sea, about dunes, about the wind. When I was little, some neighbours had a lot of artefacts from Africa. I was fascinated and asked my Grandma, ‘Where’s Africa?’ She said, ‘It’s across the sea, laddie.’ For quite some time afterwards, when I looked across the Firth of Forth to Berwick Law and the Lothian coast, I thought I was looking at Africa.

Clive Russell as Brynden ‘Blackfish’ Tully in Game of Thrones

I was brought up in Leven, which used to be a mining area. When I was at school, maybe forty per cent of the children were the sons and daughters of miners. Now there are none, so it’s changed a lot. The unemployment rate is high and the town has a reputation for being quite tough. There’s a sense of something missing. I went to Buckhaven High School and was extremely good at sport, especially golf, athletics and rugby. By the time I was 16 or 17, I was already 6ft 5ins and covered in spots so I was fantastically shy and self-conscious. The only place I felt empowered was on stage. If you can make people laugh, it makes life a lot easier.

I guess I was the spotty kid at school saved by drama. I had a teacher called Jean Dingwall who really inspired me. We were doing a performance of The Shoemaker’s Holiday by Thomas Dekker and Marilyn Imrie, who is now a famous BBC producer, forgot to come on so I was left on stage making it up. When I came off stage the teacher said to me: ‘You know something, you’re a born actor.’ I think she was just being encouraging, but I never forgot it.

When I was 17 I wanted to be the Open golf champion, play rugby for Scotland, write a novel and be an actor. I wanted to be everything but at the same time was pretty convinced I would never do any of those things.

After school I went to train as a teacher in English, drama and physical education. I taught for a year in a small primary school in Leicestershire which had an absolutely inspirational head teacher and I loved it, but an opportunity came up to join the Octagon Theatre in Bolton. It was a repertory theatre set up in a provincial town in 18 months. I guess at the time it didn’t seem that amazing, but looking back it was pretty impressive to build something that fast. In the 1960s, everything seemed possible. There was a Labour government and there was a lot more money for arts and the theatre back then.

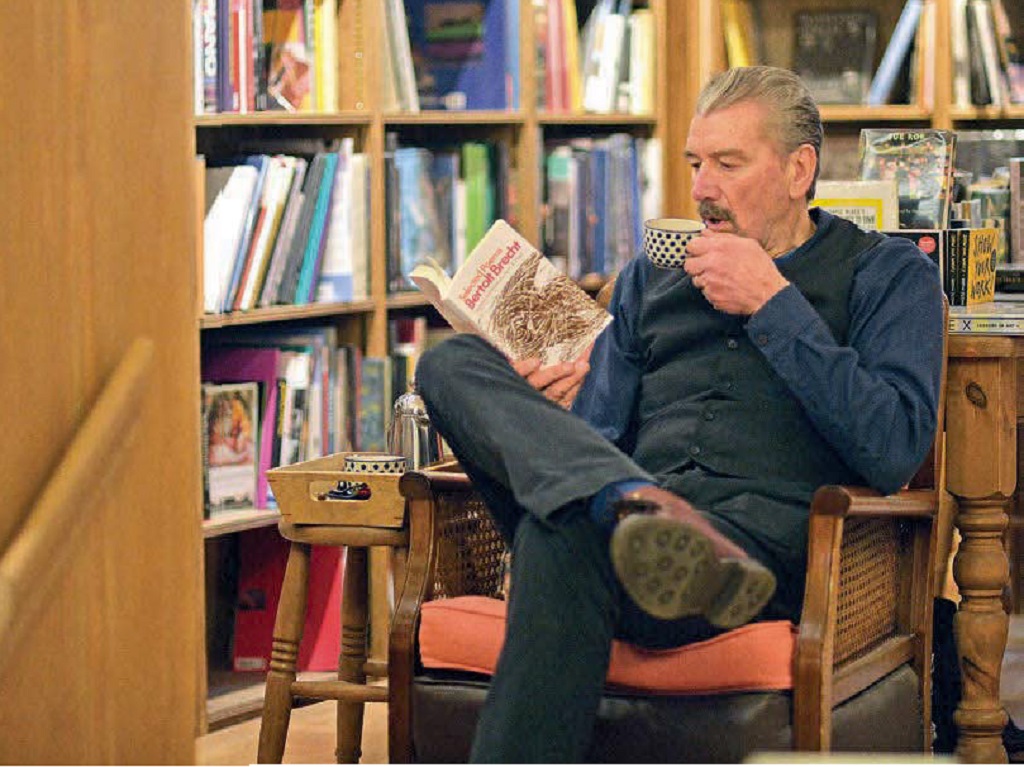

Clive Russell enjoys poetry, which seems at odds with his character in Game of Thrones (Photo: Angus Blackburn)

I thought I would spend the rest of my career in that kind of ‘educational theatre’. It was quite alternative at the time, with lots of left-wing, feminist, socialist ideas. The 1970s were a very turbulent time politically. I was with a feminist touring company, the Monstrous Regiment, for a while. Looking back, we did shows that were quite controversial, educating kids about working-class history and so on.

I never expected to go to London and the West End but I was offered a part in Accidental Death of an Anarchist with the company Belts and Braces. I was looking after two children at the time, doing my share of the childcare, but somehow I managed it. It led to more plays, at the Liverpool Playhouse, Royal Court and Young Vic, all within four years.

It is very possible to look back from this point and see a career as constructed, but the truth is you tumble from one thing to another. Someone says, ‘Come to the West End’, then people see you in productions and it jumps forward from there.

I moved down to London in 1984 with my second wife, a theatre designer with the Young Vic. During that decade I worked with the Royal Shake speare Company in a number of plays which was both exciting and terrifying.

In a sense, I did not think of myself as an actor; I felt like I was part of a group of people doing good plays about good things. But then I realised that everyone feels like that. I worked with great actors like Fiona Shaw and it gave me a lot of confidence.

The very first piece of television I did was when I was working at the Liverpool Playhouse and I played the traffic cop in the first episode of Boys from the Blackstuff. I think I got paid £150 for it. I didn’t have an agent. It’s very different now.

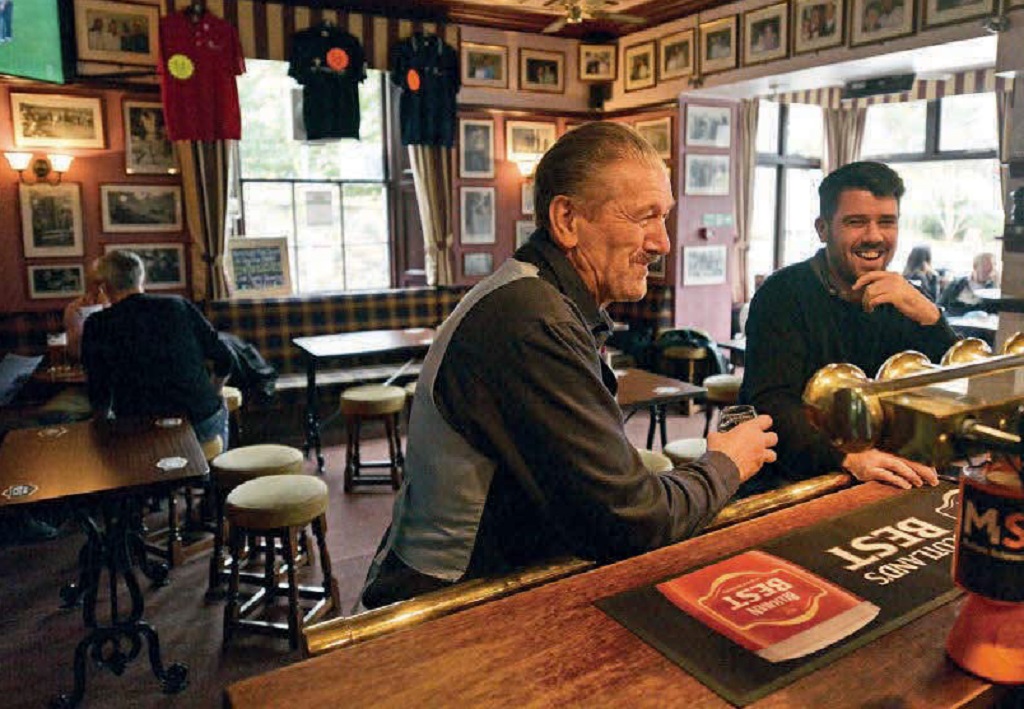

Clive is recognised as Big Yin Innes from Still Game, with people often offering to buy him a Midori at the bar. (Photo: Angus Blackburn)

By the 1990s I had really moved into television and was only very occasional dipping into theatre. I had four children to feed. My career in TV and film was driven by that reality, but I always sought interesting work, whether it was an interesting script, director or just other actors.

I’ve been lucky enough to do some good work. I love doing the classics, like Great Expectations or Middlemarch. Coronation Street was also a great experience. It is an institution and some of the work I observed there was of the highest quality. Hollywood came later. As a big man, I‘ve often been cast as a warrior or knight. I played Tyr in the Thor series and MacQueen in Wolfman. I have been in A-List films, but I’m not starry. I’m not concerned with status. I love the work and invest as much as I can in it, and then go home. I seldom watch the films back. It always looks like someone else playing the part.

In many ways my physique has kept me working. If a big man stands there in armour, it says ‘warrior’. But a big man can also be gentle, like Joe Gargery in Great Expectations, or funny, like Big Yin Innes in Still Game. A lot of big parts came when I was older.

I learned to ride horses when I was 51, for example, on a film called The 13th Warrior. It starred Antonio Banderas and was shot in British Columbia. I loved it from the word go. My horse was 21 hands high – try getting on that in full armour!

Being able to ride has helped in many roles since. I have learned all sorts of styles, and in many ways I wish I had learned when I was a child. It has certainly helped in the casting of warrior parts like Game of Thrones.

I knew a lot of people who worked on the first season of Game of Thrones and they approached me pretty early on. Blackfish Tully is a great part, although I think I play a harder character than he appears in the book. A lot of the time he’s trouble. He is a family man, but also a fearsome warrior.

Clive Russell at St Andrews

harbour (Photo: Angus Blackburn)

I have read the books, but in truth, if you are doing an adaptation, the script is your bible not the novel. I made the mistake of reading the blogs and listening to the fans. They thought someone like Jeremy Irons should play the part. There are also a lot of conspiracy theories. At the end of season three at the ‘Red Wedding’, where most of his family are murdered, Blackfish slips out to the toilet. I can’t comment on what he does next. All I can say is that he is still alive…

I am starting to be recognised as Blackfish Tully, but most people are still catching up on seasons one and two of Game of Thrones. In Scotland, I’m more likely to be recognised as Big Yin Innes from Still Game. People still make jokes about it and buy me a Midori at the bar.

I love the humour and friendliness of the west coast. People are more reserved on the east coast but I have always loved its landscape more. I had a wonderful family home in London and had no plans to come back up to Scotland. But we were beguiled by happy Scottish family holidays, so in 2010 after I did a one-man show at the Edinburgh Festival we made a decision to come back to Fife.

Now I am a London-based actor who lives in Fife. You have to be disciplined and go to the casting auditions. If you don’t do that, you don’t get the work. But I don’t find it too difficult. I love trains, and the East Coast is beautiful. I sometimes get the sleeper or go down at 6am and come back in the evening.

I have four children, aged 38, 37, 29 and 26, and three of them are in London, so I’ll visit them and go to galleries. I am still a member of the Tate and the Photographers’ Gallery.

I travel a lot for work, but I love coming home. When I’m in Fife, I read, walk the dog and go to Dundee Contemporary Arts to watch films. My wife was brought up in the city, but she loves Fife. She is a Pilates teacher and is very sociable and has made a lot of friends. I love St Andrews – the picturehouse is the same as when I was a boy, slightly rundown, like the one in Cinema Paradiso.

Clive Russell loves golf and is a member of a number of clubs( Photo: Angus Blackburn)

The landscape is all part of it. You can walk from Crail to St Andrews and you’re never more than 100 yards from a golf course, yet it’s so wild you could be on the Isle of Harris. I’m a member of a few golf clubs – my handicap is 4.8. I used to play off one when I was younger.

The trouble with being an actor is you work mostly in the summer and it gets in the way of your golf – I say that with great bitterness.

My wife Shelagh and I both grew up by the sea, so living in Cellardyke feels like coming back to the seaside. We live in the street above the shore looking out to St Abbs Head and North Berwick. It is more exposed than Leven – you can look out to the North Sea and towards the steppes of Russia. I love the sea – the rhythms of it, the tides, the mood, the wind.

There are moments in midwinter when you can see the sun come up over the Isle of May and go down over Edinburgh Castle – it never gets that far above the horizon. And there are moments when it is almost light all night. The sky is different every day. It is thrilling and terrifying and life-affirming. Norman MacCaig and a number of other poets capture that.

I love to read poetry. I feel poetry is a bit neglected. The idea of distilling thoughts into four or five lines is extraordinary. I enjoy political poets such as Gil Scott-Heron and John Cooper Clarke, and also local modern poets like Don Paterson and Kathleen Jamie.

Poetry is a way of talking about the physical world – the confluence of landscape, seascape, birds, animals, all of which is life-affirming. I think it gives us a sense of the sublime, the kind of thing we experience when we are in love, in front of a painting, or looking at a landscape. I have always been drawn to the sea – it’s good to be back in Fife but still working as an actor. It has all been a glorious surprise. I mean, I’m still doing it. How lucky is that?

(This feature was originally published in 2015)

TAGS