Tinkering with Volkswagen engines and photographing abandoned houses in the Outer Hebrides may be a million miles from the Manchester punk scene of the late 1970s.

But that’s exactly where Buzzcocks drummer John Maher finds himself three and a half decades after the legendary band split.

The Isle of Harris is a world away from the whirlwind of high-energy gigs that was the norm for the teenage Maher, but it’s a place that has long fascinated the former musician.

‘I always had an interest in the Outer Hebrides,’ he says. ‘As a kid I thought it had this aura about it and when I saw something from there on TV it always looked really interesting.’

He first visited Harris with his wife Helen in 1992. The couple made a permanent move to the island a decade later, with Maher switching John Maher Racing, his vintage Volkswagen performance tuning workshop, from Manchester to Leverburgh.

‘I was still in the Buzzcocks when I first got into Volkswagens,’ he says. ‘I got disillusioned with the whole music thing in the 1980s and went off in another direction. After the Buzzcocks split I needed to do something to earn a living. I got some leaflets printed up and I’d drive around Manchester slapping them under the windscreen wipers of any VWs I saw.’

In 1987 the UK staged its first VW drag race. ‘I saw them going round the track and I wanted to get involved,’ Maher recalls. ‘I bought a 1957 VW Beetle and raced it at the event in 1988. There wasn’t a lot of competition there, and I won. I carried on racing and got some press in the VW magazines that were around at the time. People started contacting me and I went from doing general repairs and servicing to focusing more on the engine side of it. By 1990 I was purely building fast engines for VWs.’

Maher didn’t have an engineering background or any mechanical qualifications, but he wasn’t going to let a little thing like that put him off. ‘I ended up turning a hobby into a job,’ he says. ‘I think I got spoilt early on by joining the band at such a young age – I’ve never really had a ‘proper’ job, I’ve always ended up just doing things I’m interested in. With the drumming it was something that I was into so I taught myself, and it was the same with the engines. If there’s a need to know how to do something, I’ll find out how to do it, one way or another.’

It’s that philosophy that helped him produce some of the most striking, unusual images of the Hebrides, which later formed part of Leaving Home, a collaborative exhibition from Maher and Fife photographer Ian Paterson which was unveiled to critical acclaim in Stornoway in 2013, just four years after the islander began experimenting with photography. ‘I always had a camera but I never went as far as figuring out apertures and all that kind of stuff, it was more just a point-and-shoot,’ Maher admits.

Often featuring abandoned homes, machinery or other remnants of forgotten human activity, Maher’s images offer an alternative to the Hebrides photographic vernacular of wide sandy beaches, flowering machair, standing stones, and dramatic vistas and weather. ‘That style of photography never really interested me and so for years I didn’t actually take the camera out of its case,’ he says.

It was a documentary on Sky Arts in 2009 about Californian photographer Troy Paiva that prompted Maher to dig out his camera again. ‘He was going out into the deserts, taking long exposures at night, and I was really taken with the images he produced. I looked him up on the internet and there was a book of his out, and there is a part in the book where he gives a brief rundown of how he was doing it. I thought, “I’m going to give this a go!”

‘The amazing thing is that the result you see in the camera or on the screen isn’t something you can see with your own eyes at the time. That image has come about because of an accumulation of time, and you’re adding light. The camera records that and you look back at it as a still image and think, “Wow, did I make that?” I got really into it.’

True to form, Maher stepped away from Paiva’s guide and taught himself the technical ins and outs of long-exposure photography. He quickly amassed a collection of night shots featuring abandoned buildings, old caravans and disused telephone boxes, mostly shot against deep blue skies sprinkled with stars. ‘A lot of it is the consequence of living in a place like this,’ he says.

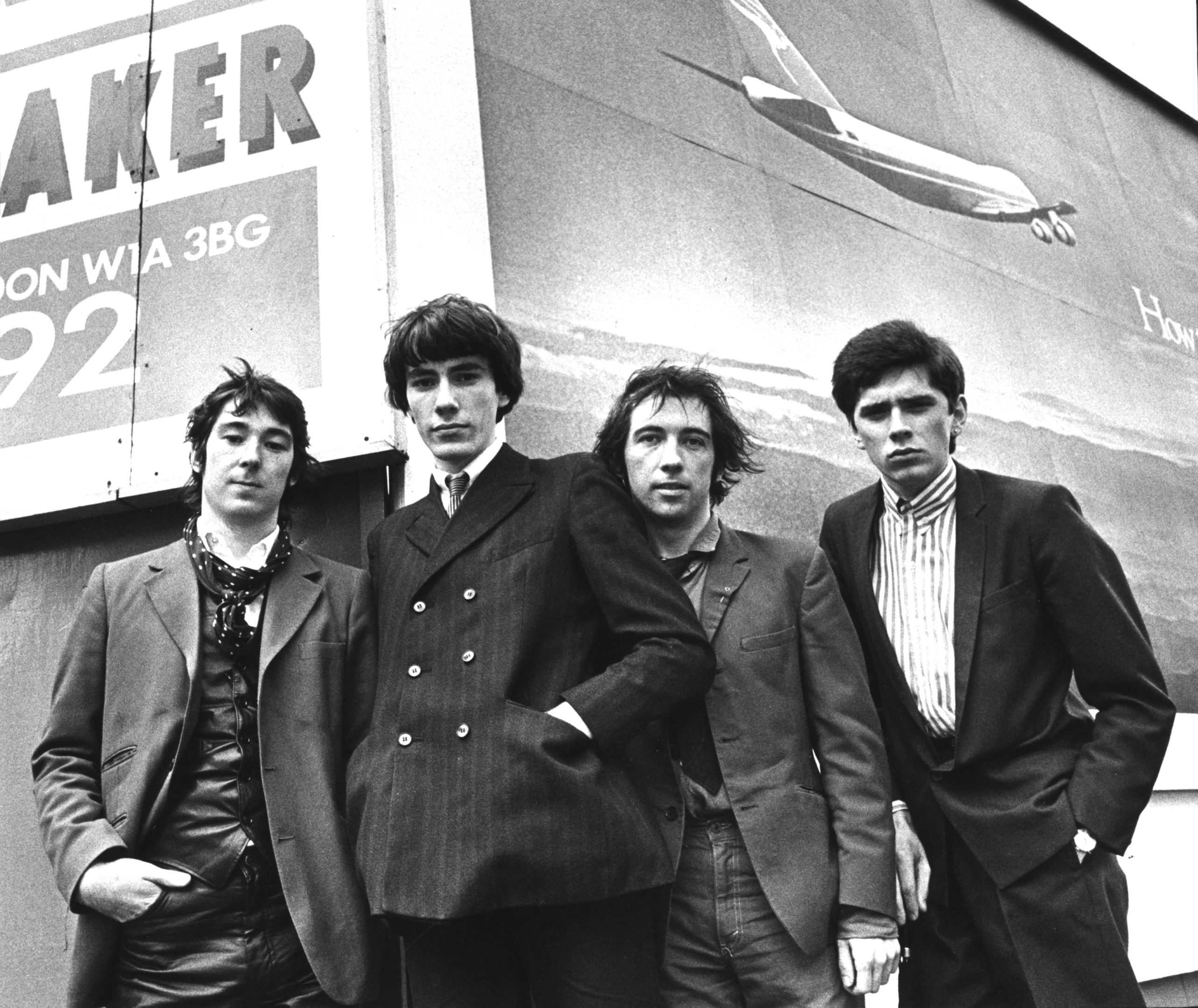

John Maher (second left) pictured with the rest of The Buzzcocks in their heyday

‘There are no street lights so you don’t get that horrible orangey light coming in to spoil the picture. I liked to include something like an old house or tractor against this amazing scenery. In a tourist board photo you wouldn’t have the ruin or the tractor because for them it would spoil the image, but for me it makes it. I’m interested in the fact that people can live in a very remote place like this.’

The often eerie images led on to the Leaving Home shots of dusty interiors, capturing moments frozen in time. Some of the buildings, mostly former croft houses, have stood untouched for decades. ‘I found it absolutely amazing when I first stumbled across one,’ Maher says.

‘I was out doing the night photos and I’d go inside some of the ruins to light them. Of course when you go into one of these houses you’re stumbling around with a torch, and in one I could see there was a table there with stuff all over it, and a suitcase on the bed where it looked like somebody was packing. It felt very like the Mary Celeste. Where did they go? Why did they leave everything? The thought that it had obviously been empty for 20 years was fascinating. I couldn’t believe all the stuff was still there.’

He began searching out abandoned homes. ‘It got quite addictive, to be honest,’ Maher admits. ‘I was driving around all over the place looking for houses that might be likely candidates, and then I’d stop and walk up to one, and there would be this excitement of what it would be like.

Blue Door – Isle of Harris

‘In one house there was a mantelpiece with a picture of a dog on there and a picture of a cat, and plastic cups from the 1974 New Zealand Commonwealth Games. There was lots of photographs and paraphernalia from the 1950s and the guy had obviously been in the Navy. Sometimes it’s quite weird standing in a room, surrounded by all this stuff and imagining what the hell went on there.’

Having spent much of 2015 travelling back and forth from Harris to Newcastle, recording a new album with ’80s rock band Penetration, the photography took a back seat. But with the resulting, much lauded Resolution album released at the end of 2015, Maher is looking forward to getting out with his camera again.

Forty years after helping to shape punk Britain’s musical landscape, the enterprising drummer is living his life to a different beat – and it’s one that suits him just fine. ‘Moving to Harris was a bit of a leap of faith. It wasn’t possible to line everything up in a row and say this is the sequence in which it’s supposed to happen. We just had to go with the flow and trust that things would work out,’ he says. ‘We’ve been here coming up for 14 years now and it’s home. I definitely have no regrets.’

This feature was originally published in 2016.

TAGS