Nick Lindsay, Chairman of the Clyne Heritage Society, takes a look at the life of world famous salmon fly-dresser Megan Boyd, as plans for a new statue in her memory are unveiled.

From humble beginnings in Brora, on the east coast of Sutherland, Megan Boyd became, arguably, the finest and most famous salmon fly-dresser the world has ever seen.

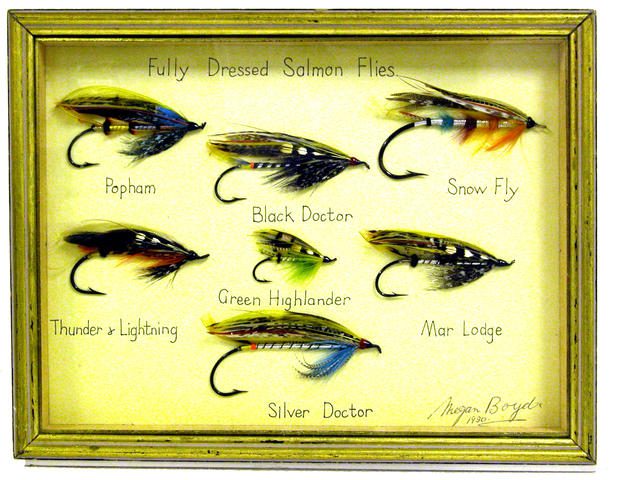

Works of art and labours of love, Megan’s exquisitely crafted flies were highly sought after by top fly-fishers, including celebrities and royalty, such as the then Prince Charles, with whom she became a good friend.

She presented Charles and Diana with a specially designed fly ‘White Lady’ as a wedding gift. Since her passing in 2001, her flies have sold for thousands of pounds – a collection of 47 of her flies sold for £22,000 at auction in 2018.

A film, Kiss the Water, was made of her extraordinary life and a popular book of her story sells well to this day. Not bad for a lady from Brora.

Now, Clyne Heritage Society aims to immortalise Megan’s story with a spectacular tribute at its new community heritage centre and museum, opening in July 2025.

This tribute, a breathtaking 5m-high sculpture of a Blue Doctor salmon fly, will be designed and fabricated by renowned local sculptor, Jon Asanga.

Towering in front of the Old Clyne School on the A9 North Coast 500 route, the sculpture will not only commemorate Megan’s artistry but also serve as a striking landmark, drawing tourists and Megan Boyd enthusiasts from around the world.

An inspiring life

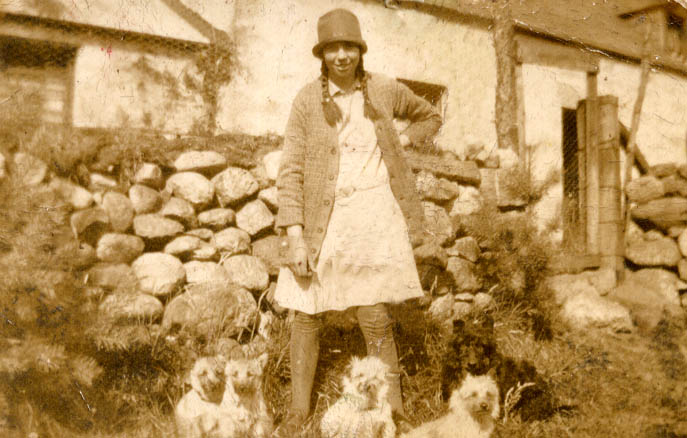

Born in Surrey during the Great War in 1915, Megan’s family moved to the small Scottish Highland village of Brora, when she was three-years-old.

As a young girl living in the beautiful Highland countryside, and with her father patrolling the river as a water bailiff and mixing with gentry fishermen, she became exposed to the art of salmon fishing.

She developed a fascination with the beauty and intricacy of fishing flies – more specifically salmon-fishing flies – and set herself the task of learning all she could about the art of dressing them.

She did this, principally, by reading avidly a book that was to become, as she later described it, her bible: How to Dress Salmon Flies’, by T E Pryce-Tannatt.

From it, she gleaned all she needed to know about the theory of salmon fly-tying, although she also referred to ‘The Salmon Fly’, by George M. Kelson, published in 1895.

In this way, Megan acquired an exhaustive knowledge of the names, origins and qualities of salmon flies which she could later draw upon as required, and which would equip her for almost six decades of professional fly-tying.

Having already taught herself the theory of fly-tying she now, at the age of 12, began to get the practical experience she needed under the tutelage of her father’s fellow estate worker, Bob Trussler, a Ghillie and Water Bailiff on the River Brora, which set her on the path to her life’s work.

Throughout the next few years, Bob’s expert guidance placed emphasis on precision and quality. He would begin his tuition by getting Megan to undo a dressed fly and then re-tie it on a smaller hook, and Megan took readily to the intricate practical skills of dressing the metal fishing hooks.

With an excellent eye for colour and detail, she soon took the craft to a new level, deftly fixing the colourful, delicate feathers, furs, hairs, tinsels and threads in place and creating a work of art with each one.

Rising demand

By the age of 15, when she had left school, she was selling her flies to local anglers. The story is told that she used the proceeds from her first sales to buy her father a suit and, with what was left over, she purchased the supplies she needed to tie more flies.

She was a quick learner and her reputation for making successful salmon-catching flies soon grew. Fishermen who came to try their luck locally on two of the finest salmon rivers in the world, the Brora and the Helmsdale, began to seek her out for her wares.

She could not keep up with demand, but always prioritised local fishermen above those from afar. Ironically, Megan never fished herself, saying that she preferred to catch the fishermen instead.

When she was 20, in 1935, Megan’s father retired. Megan moved with her parents to a tile-roofed, corrugated iron cottage overlooking the North Sea just to the north of Brora, at Kintradwell on the Gordonbush Estate.

It had a neat little garden, well-stocked with flowers, but there was no mains electricity in the cottage and water was collected from a nearby stream – there were few luxuries in those days.

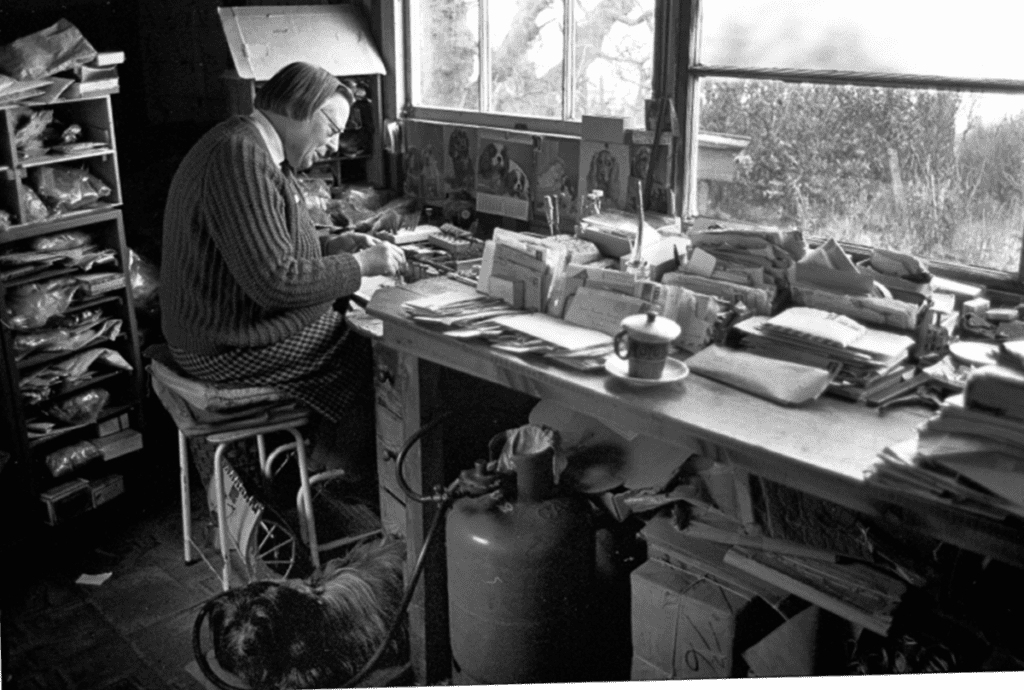

Megan worked close to the window during daylight hours, however, after the light began to fade, the family had to use gas lamps. Megan sat at a kidney-shaped table in front of the large window looking out over fields to the North Sea, with her constant canine companion at her feet, and surrounded by customers’ orders and the tools and materials she needed for her trade.

She continued to tie her flies for her expanding order book under candlelight.

During the Second World War, she was an Auxiliary Coastguard; her front room overlooking the sweeping, sandy beach below and the Moray Firth beyond.

Well deserved recognition

After the war, Megan’s reputation continued to grow. Flies tied by her were highly rated by anglers, fellow fly-tyers and authorities on salmon fishing alike.

Recognised as being of exceptional quality and durability, lasting for many seasons, they were entered into competitions and won prizes: in 1938, her creations won the Open Award at the Empire Exhibition in Glasgow.

Many of the traditional flies required the use of plumage from exotic birds such as Italian crow, kingfisher and jungle cock, which had to be imported, often under licence.

Megan bought from well-known firms. Her suppliers, in turn, on seeing the quality of Megan’s work, became interested in making reciprocal arrangements, whereby Megan fulfilled bulk orders for dressed flies for retail by the companies, often overseas and mainly in the USA.

Anglers who had heard of the success Megan’s flies achieved, as well as of their durability and longevity, frequently stopped at her house to order supplies for themselves. Megan would spend up to 14 hours a day tying salmon flies to meet the increasing number of orders she received.

Without electricity at her cottage, there was no television or telephone, and orders for her flies had to be given to Megan either by post or in person.

If visiting anglers found her away from home when they called, they would write down their orders in the notebook she left in a plastic bag by the front door.

If they were lucky enough to find her in, they might stop for a while to watch her work as well as to have a blether and place an order.

The appreciation of flies dressed by Megan as objects of beauty, as well as of practical value, was also acknowledged by orders for flies to be made up as brooches, and for wall displays.

A sixth sense

Megan had a deep love and detailed knowledge of the local lochs and rivers. Together with her encyclopaedic recall of the numerous salmon flies available meant that, despite never having attached a fly to a line herself, or even having been fishing, she seemed to have a sixth sense about which fly would be most suited to which specific waters, weather conditions and times of year, and was able to give useful tips and advice to the anglers who called in.

Never marrying, Megan enjoyed socialising in the village at whist drives and excelling at local Scottish Country Dance rallies.

Awarded the British Empire Medal in 1971, she politely declined the invitation to receive her medal from the Queen at Buckingham Palace because, she said, she couldn’t find anyone to look after her dog.

Understanding her plight, Her Majesty responded to Megan telling her that next time Charles was fishing in the area, he would bring the medal and present it to her himself.

In the 1980s, with failing eyesight, she moved from her isolated home to sheltered accommodation in the Brora village, finally living the last few years of her life in a care home in neighbouring Golspie, where she died in 2001, aged 86.

To donate to this project contact Nick Lindsay, Chairman of Clyne Heritage Society at info@clyneheritage.com.

Read more News stories here.

Subscribe to read the latest issue of Scottish Field.

TAGS