Scotland and England – the best of enemies

Scotland’s World Cup team are just over a week away from their opening fixture in the 2019 World Cup.

With Ireland, Samoa, Russia and Japan lined up between 22 September and 13 October, the Scots will be determined to progress from their group.

While those fixtures all pose their challenges, there is no other rugby clash like the one which decides the destination of the Calcutta Cup each year, when Scotland face England.

George Orwell once quipped about rugby being ‘war by another name’.

As soon as the first international rugby match drew to a conclusion at Edinburgh Academicals’ Raeburn Place ground on 27 March 1871, an overexcited, blackgowned figure rushed on to the field of play to congratulate the victors – and to gloat over the losers: ‘Flodden is at last revenged!’ roared Edinburgh Academy master James ‘The Skinny’ Carmichael as the vanquished English trudged off the pitch.

With the first cricket Test match and the first official football international yet to be played, this groundbreaking meeting of England and Scotland on the sports field had proved a suitably controversial and incendiary affair. That match in 1871, won by Scotland by the narrowest of margins, was as heated and hard-fought as virtually any of the 126 that have followed between the Auld Enemies, with Carmichael’s taunt completely in keeping with an event that raised passions on both sides.

The cause of the match, after all, was the offence taken by Scotland’s sporting fraternity at what they saw as English grandstanding in 1870, when the newly formed Football Association had staged a soccer match at the Kennington Oval between England and a team that was purported to represent Scotland.

Played under FA rules and with both teams chosen by the FA, the match pitched the finest English players against a motley crew of ‘Scots’ of extremely dubious heritage. Goalkeeper Alexander Morten merited inclusion because he possessed ‘a Scottie dog and a fondness for whisky’, fullback William Lindsay had never set foot in Scotland, while Welsh MP William H Gladstone, whose father was soon to become prime minister, qualified for Scotland on the basis that his family had a sporting estate in Aberdeenshire.

The Auld Enemies quickly developed a deep rivalry after their first rugby clash in 1871

Even though Scotland almost won that match on 5 March, a late goal making the final score 1-1, the perception that the ‘Scotland’ team was full of unrepresentative and substandard players caused a firestorm of criticism north of the border.

When in late November 1870 England comfortably won a second match against a team boasting just one man from Scotland, FA chairman CW Alcock, who had proposed and organised what was intended to be a four-match series, was forced to write to The Times: ‘I must join issue with your correspondent in some instances. First, I assert that of whatever the Scotch eleven may have been composed the right to play was open to every Scotchman [Alcock’s italics] whether his lines were cast north or south of the Tweed and that if in the face of the invitations publicly given through the columns of leading journals of Scotland the representative eleven consisted chiefly of Anglo-Scotians… the fault lies on the heads of the players of the north, not on the management, who sought the services of all alike impartially. To call the team London Scotchmen contributes nothing. The match was, as announced, to all intents and purposes between England and Scotland.’

With influential Loretto headmaster Hely-Hutchinson Almond leading the backlash, the leading Scottish rugby players of the day convened an emergency meeting after a match between Edinburgh Academicals and Merchistonians. The result was a challenge which was published in The Scotsman in Edinburgh and Bell’s Life in London on 8 December, signed by representatives of the leading Scottish clubs, West of Scotland, Glasgow Academical, Edinburgh Academicals, Merchistonian and St Salvator from St Andrews.

‘Sir, There is a pretty general feeling amongst Scotch football players that the football power of the old country was not properly represented in the late so-called International Football Match… Almost all of the leading clubs play the Rugby code [so] we therefore feel that a match played in accordance with any rules other than those in general use in Scotland, as was the case with the last match, is not one that would meet with support generally from her players. For our satisfaction, therefore, and with a view of testing what Scotland can do against the English we, as representing the football interests of Scotland, hereby challenge any team selected from the whole of England to play us at a match, twenty-a-side, Rugby rules, either in Edinburgh or Glasgow on any day that might be suitable to the English players.’

The challenge was eagerly accepted by England’s leading rugby clubs, with Blackheath’s secretary, Benjamin Burns, charged with organising a team. Several rules had to be clarified or changed, not least the number of players, with England only abandoning their insistence on 15-a-side in late February. While Burns selected 12 men from London and four each from Manchester and Liverpool, the Scots hastily organised trials in Glasgow and Edinburgh before picking a fearsomely fit team to combat England’s inventive and speedy backs. While England chose seven backs in their team, Scotland went with just six, while the home captain, the Honourable Francis Moncrieff of Edinburgh Academicals, chose the narrow confines of Raeburn Place for the venue (despite the protests of several members of the cricket club who usually played there) and the date of Monday, 27 March 1871, was soon settled upon.

Among those chosen on both sides were some genuinely interesting Victorian gentlemen, many of them from clubs such as Merchistonians, St Salvator, West Kent, Gipsies, Clapham Rovers, Marlborough Nomads and Ravenscourt Park that are no longer in existence.

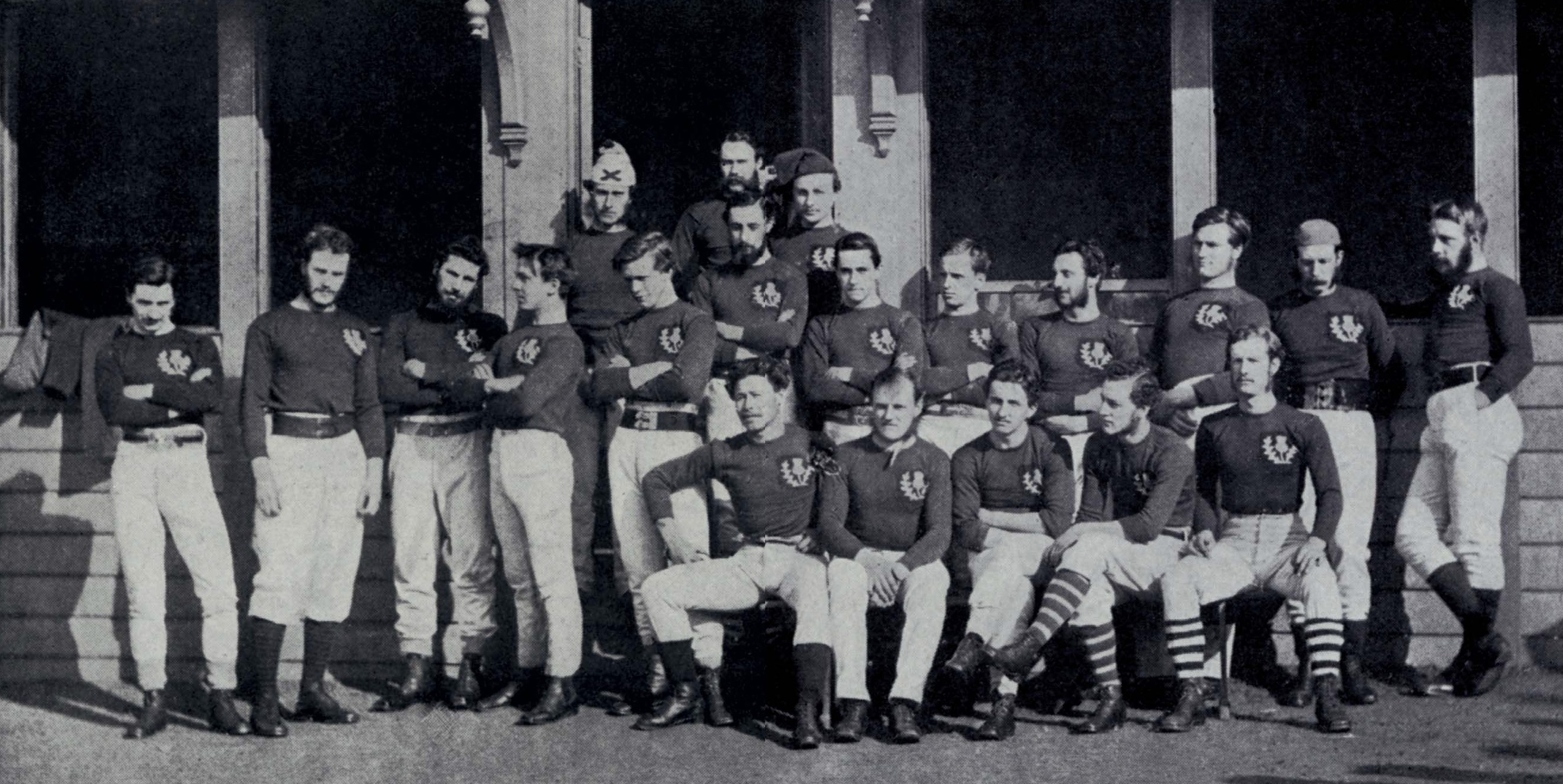

The Scotland XX in 1871 that took on England

The organiser on the English side, Perth-born Benjamin Burns, had been educated in St Andrews and at Edinburgh Academy before moving to London to work as a banker, and a late call-off meant he stepped in at the last minute to play for the English. He would take to the fi eld alongside men like FA Cup-winner Reg Birkett, the first rugby-football dual international, and 17-stone Liverpudlian John Clayton, who would run four miles before breakfast with his newfoundland dog before riding five miles to his office, and then rounding off the day with a huge bowl of rare beef and beer.

One of Burns’s best friends and speedy Blackheath teammate was Andrew Colville, an English-born banker who had attended Merchiston Castle school and who turned down repeated invitations to play for England to turn out for Scotland instead. The Anglo-Scot’s teammates included the legendary hardman Robert ‘Bulldog’ Irvine, who was then a 17-year-old schoolboy at the Academy but who would go on to win a record 13 caps over the following decade, plus the Jamaica-born Andrew Macfarlane and Dundee footballer and Test cricketer Alf Clunie-Ross, one of several half-Malay brothers studying medicine in Scotland. With seven teenagers on display, including 19-year-old English skipper Fred Stokes, both teams were unfeasibly young, with the Scots averaging 21 and the English 22.

The match, played in glorious sunshine in front of 4,000 raucous spectators paying a shilling each, turned out to be a thrilling match full of controversy and bone-jarring tackling. The only converted try (unconverted tries didn’t count at the time) came just before half-time, when the Scots made the most of their dominance by pushing Royal High School’s Angus Buchanan over the line for the fi rst try in Test rugby, which was converted by William Cross.

It proved to be the winning score. The English, however, were convinced that Buchanan hadn’t managed to touch the ball down and protested long and hard. Referee Hely-Hutchinson Almond wouldn’t change his mind, though, arguing that ‘when an umpire is in doubt I think he is justifi ed in deciding against the side which makes the most noise. They are probably in the wrong.’

It was a decision that was to rankle for years to come and later led to a breakdown in relations. But at the time HH Almond was feted in Edinburgh for his wisdom and refusal to budge.

TAGS