The iceman cometh – the amazing life of Doug Allan

Film-maker Doug Allan has made a career out of working in the most inhospitable conditions known to man.

However, it’s safe to say that most people would not recognise Doug Allan.

However, it is equally true that they will have been mesmerised by his spectacular footage of the natural world on programmes such as The Blue Planet, The Life of Mammals and Planet Earth.

Ironically, it was an encounter with the narrator of these programmes, the iconic David Attenborough, in the Antarctic that influenced Allan’s decision to become a film-maker. It was an initial interest in diving that led Allan to Antarctica.

‘When I was growing up,’ he recalls, ‘my love of the sea was sparked by a combination of reading Silent World, by the legendary Jacques Cousteau, and going on package holidays to the Mediterranean and swimming in the clear, blue waters. In the Sixties there were two great frontiers: space and the sea; obviously space was out of the question.’

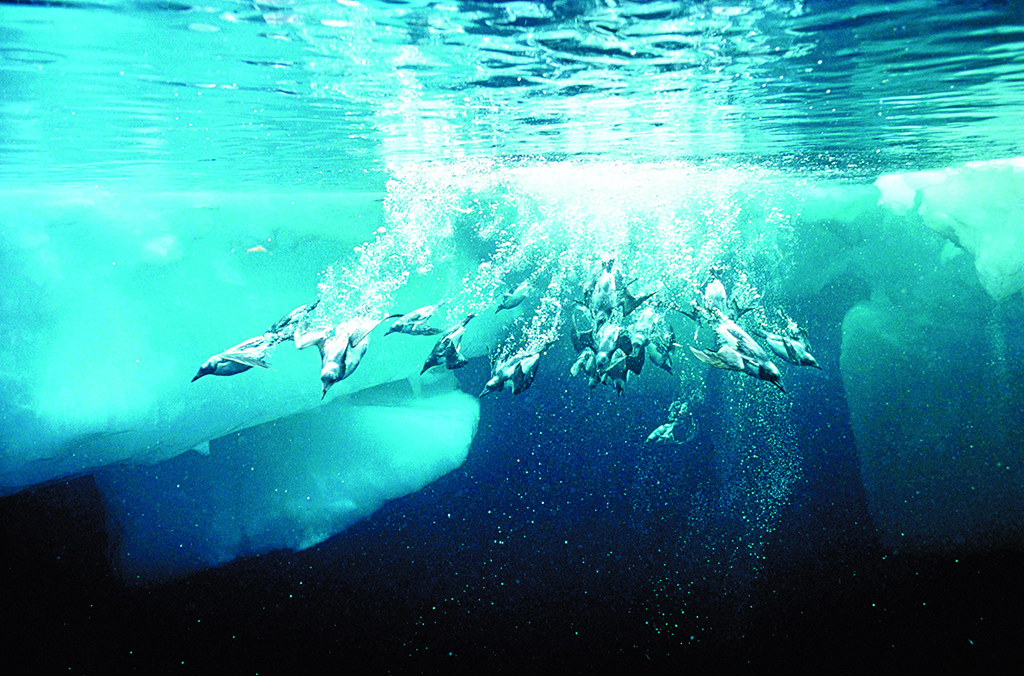

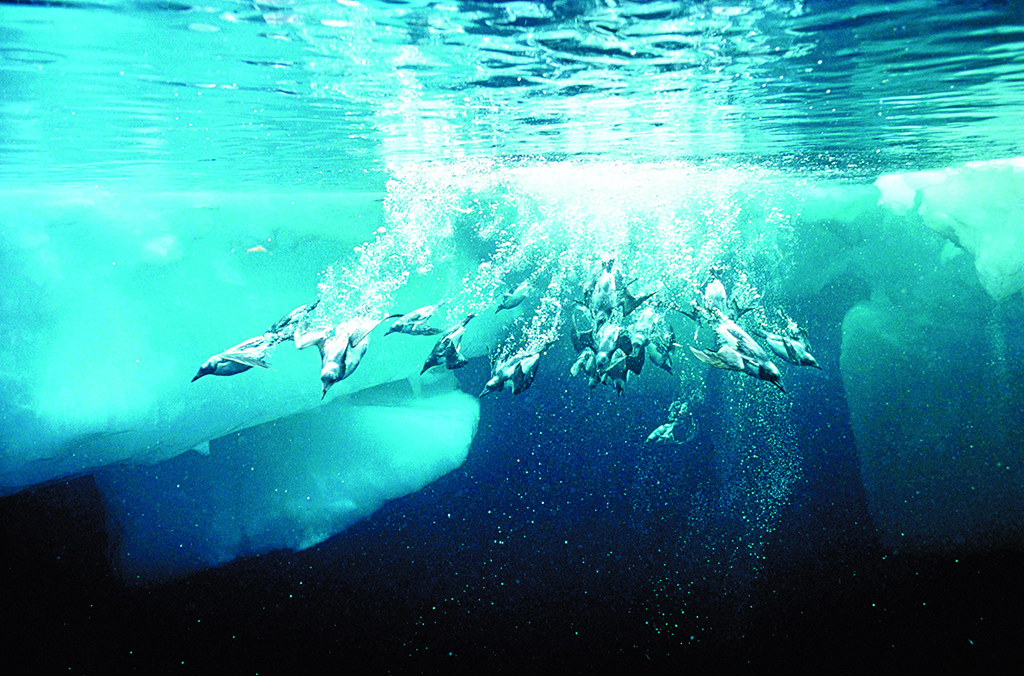

Moments after filming these guillemots, Allan was dragged down by a juvenile walrus and was lucky to escape (Photo: Doug Allan)

In 1976, after a degree in marine biology and a number of different diving jobs, Dunfermline-born Allan joined the British Antarctic Survey. ‘It really changed my life,’ he explains. ‘I wasn’t into photography when I went to the Antarctic, but making movies was a great way of showing people how special the place was.’

In 1981, David Attenborough came to the Antarctic with a film crew and Allan helped them out for a couple of days.

‘Meeting David gave me a really good insight into how the professional film-making business worked,’ he says. ‘He was also really encouraging, telling me that although I didn’t know much about wildlife I could take a good picture underwater in Left: Looking for seals to film in spring, Allan is transported around Lake Baikal by Russian fox-hunter Mischa. the cold stuff, which is certainly not everyone’s cup of tea. David made me realise that I could find a niche for myself, so I made a few films and sold them to the BBC. I then got backing for a few more projects and, in 1985, I went full time.’

Allan’s experiences filming in the coldest places on Earth are the subject of his self-published book, Freeze Frame, which is a fascinating and honest account of his many adventures – which include being grabbed from below by a hungry walrus before being dropped – in the form of short stories accompanied by some stunning images.

‘I’ve always been interested in the written word as opposed to television,’ he says. ‘I had great fun writing it, and it was also a chance to utilise a number of photographs that wouldn’t have normally seen the light of day.’ Allan seems to thrive in temperatures that most people couldn’t even comprehend. ‘I like it fresh,’ he laughs.

Doug Allan has worked on TV shows including The Blue Planet, The Life of Mammals and Planet Earth

‘If there’s no wind, minus 18 is the perfect temperature. Everything is dry, nothing melts and you can work comfortably without gloves. Anything colder is problematic, plus it limits what you can do creatively. The coldest I’ve been in is minus 40, with a wind chill factor of minus 100.’

The willingness of Allan and others like him to endure such difficult conditions has reaped its rewards. Through their skill, patience and determination we have been allowed to enjoy watching ground-breaking footage of the most incredible animal behaviour.

And in a career that has spanned almost thirty years so far, Doug Allan has been involved in filming a number of these sequences, most recently for Frozen Planet, which included the extraordinary footage of killer whales making waves to knock seals off ice floes.

‘I filmed that with another Scot, Doug Anderson,’ Allan recalls. ‘That for me was like the Holy Grail. I’d heard about the wave-washing behaviour in 1977 but there were no pictures, and I’d tried to film it on three separate occa- sions but with no joy. It was a combination of having a great team and a lot of luck – we had to locate an orca pod capable of such behaviour, the right sea ice and a producer willing to finance the whole operation – that we managed it for Frozen Planet.’

Killer whales are definitely up there on Allan’s list of favourite animals that he has filmed. ‘I also really enjoy filming humpback whales,’ he says.

Killer whales hunting weddell seal on ice floe in co-operative hunting strategy (Photo: Doug Allan)

‘They are the greatest singers in the world, it is completely correct to talk about humpback song; they have similar rhythms and cadences to our own. These songs are important indicators of sex, breeding condition and dominance. Under the right sea conditions, the lower notes of a humpback whale can travel thousands of miles.’

It is a land-dwelling mammal however, that makes the top of Allan’s list: the polar bear. ‘Amongst all the species I’ve worked with I feel the most privileged to have spent time with polar bears,’ he says. ‘It’s great to get to a level of understanding with an animal like that, where you can read its behaviour and can tell when it’s relaxed or when it might be more threatening.’

It is fascinating to listen to Allan talk about his way with the animals he films: attracting dolphins and belugas by singing into his snorkel (‘Happy Birthday seems to work well,’ he laughs), or how it might take three or four dives without seeing anything to gain the trust of the animals he wants to film.

‘You have to remember that you are in an alien environment and that these mammals, like us, have good days and bad days,’ he explains. ‘You have to tune into them.’

Young male polar bears play fighting (Photo: Doug Allan)

Allan believes that this ability to ‘tune in’ is something you either have or don’t. ‘It’s like putting adults into a room with a crying baby,’ he says. ‘With some, after five minutes the baby will be screaming more loudly than ever, whilst with others the baby will have stopped crying. I am one of those lucky people who have that gift with marine mammals.’

It is this affinity with his subjects that has allowed Allan to capture such incredible footage, but there is a real danger his films may become a record of behaviour that once was.

‘Some big things are going to happen to the world’s ecology,’ he warns. ‘Climate change is a fact; the sea ice is thinning and polar bear numbers are falling. The sad thing is that people have been saying for years that this is going to happen. We had our chance to stop it ten years ago, but now that chance is gone and we’re going to have to cope with the effects.’

Find out more about Doug Allan through his website www.dougallan.com

This feature was originally published in 2013

TAGS