A 19th century French view of life in Scotland

As Britain lurches towards the Brexit deadline of March 29, it’s refreshing to remember how positively Scotland was viewed by some of its continental visitors in the past.

Hippolyte Taine (1828-1893), one of 19th-century France’s great men of letters, and a muse to both Émile Zola and Guy de Maupassant, was a great Britophile who made at least three visits to Britain between 1859 and 1871.

On one of these trips, in 1862, he visited Scotland, stopping off first in Glasgow, ‘a great hive,’ with a population then of 375,000 inhabitants. From here he travelled by steamer along the Clyde and then up the Crinan Canal, before taking another steamer up past Glencoe, where he marvelled at Ben Nevis, ‘its peak marbled with streaks of snow’.

Disembarking at Fort William, Taine then took the Caledonian Canal to Inverness, where he spent a week before starting his return journey by train and carriage through Aberdeen and Edinburgh to England.

Taine found Scotland in general, ‘more picturesque than England and her countryside, less uniform and less manageable, [she] is not simply a meat and wool factory.’ His journey was made in summer, yet the weather was awful.

Of the weather in Glasgow, he remarked with some feeling: ‘The climate is worse than at Manchester. We were at the end of July and the sun was shining, yet I was glad of my coat. Fortunately, the human body adapts itself to its environment: I saw fully-grown girls lying on the grass by the promenade without shoes or stockings; and there were little boys bathing in the river.’

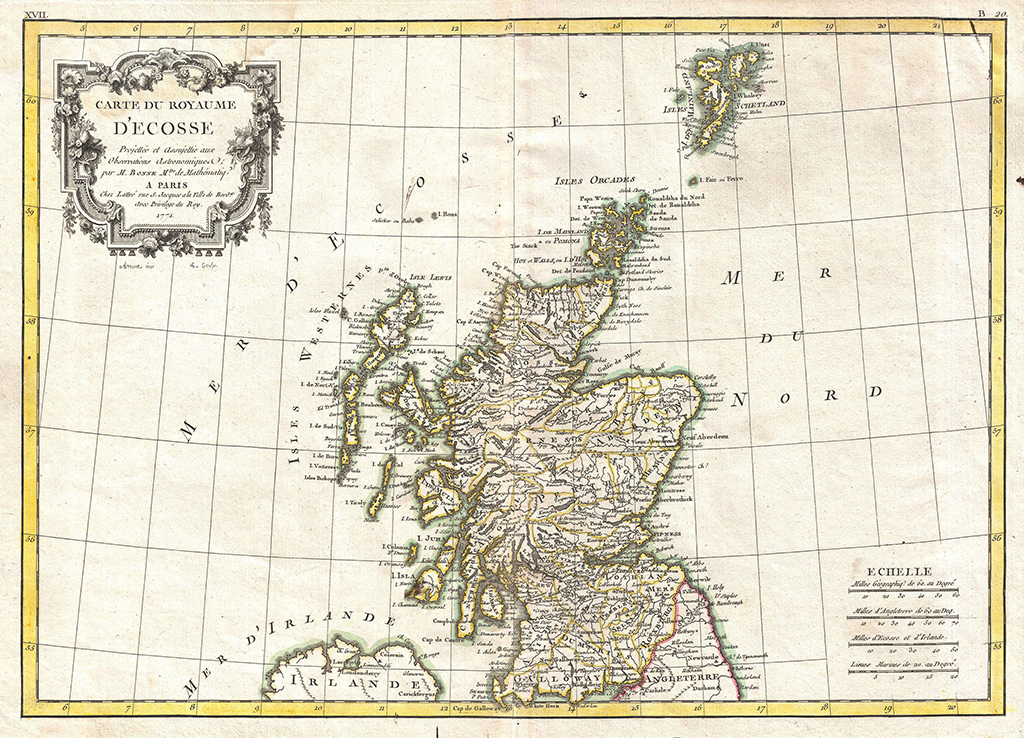

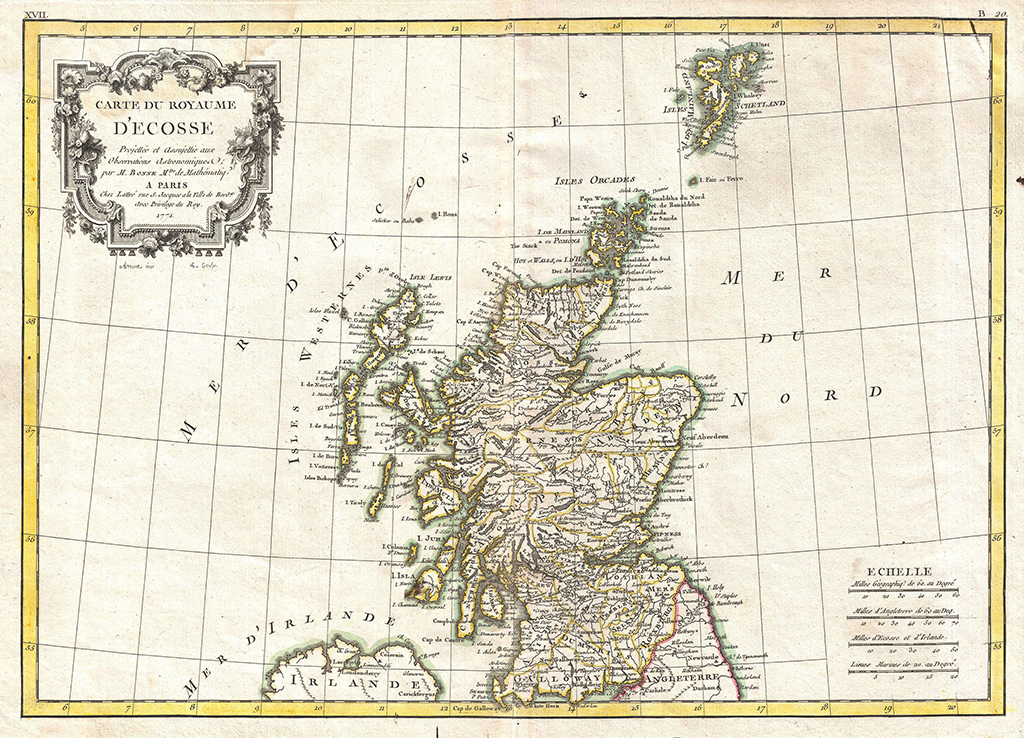

A 1772 map of Scotland in French

In Edinburgh he smiled at the disparity between the classical architecture, ‘surely more at home in a warm

climate’ and the miserable weather, ‘whipped by the wind, a pale mist drifts and spreads all over the city. The façades of buildings are drowned in the vaporous atmosphere and stand palely forth in the sickly daylight. A wisp of fog or cloud hangs upon the green slope of Calton Hill, winding in and out of the columns.’

In keeping with many other commentators of the time, Taine believed that the climate had a profound effect on the lives of the inhabitants of any country. The ‘six or eight degrees of latitude’ that separated Britain from France was, in his opinion, the cause of much ‘bodily misery and spiritual depression’, yet it also created an environment which fostered a serious temperament and good work ethic.

In Scotland, the weather and the characteristics of the people were at extremes, ‘The race is lively and more mentally active here than in England,’ he enthused.

He noted that in the Highlands, ‘There are books to be seen even in the smallest cottages; the Bible first of all, a few travel books, medical dictionaries, manuals on fishing, treatises on agriculture, eight to 20 volumes as a rule. They were the common people, but they were obviously better educated than our own villagers in France.’

But all was not sweet in Scotland according to Taine. The poor weather could also encourage dangerous pleasures: ‘The principal temptation assailing men here is to turn drunkard.’

Yet, he witnessed with admiration the work of Scottish temperance societies and churches in combating the evils of alcohol, and was impressed with levels of religious observance in Scotland.

Between Keith and Aberdeen, he ‘came across a cheap excursion train, its carriages crammed with people. They were all on their way to a religious meeting, a revival at which a number of famous preachers would be speaking.’

He went on to compare Scottish Presbyterianism favourably with what he saw as the unnecessary pomp and ceremony of Catholicism in France. In Aberdeen, while staying in a temperance hotel, he attended a Sunday service and was pleased to find ‘no pictures, no statues and no instrumental music.

The church is simply an assembly room, provided with a gallery and rows of benches, very convenient for a public meeting. The sermon was well spoken, soberly and sensibly, without oratory.’

Taine was impressed by Ben Nevis

Whilst Scotland basked in Taine’s approbation, it’s unlikely his commentary found much favour in his homeland. He describes ‘the small towns on the shores of the Mediterranean’, for example, as ‘neglected and dirty, and with the townsmen living like worms in a rotten beam!’

By contrast, he found Inverness full of ‘bustling activity, cleanliness, and attention to business.’ Here ‘the window panes shine and paths are washed down; door handles are of gleaming brass, there are flowers in every window and the poorest houses are freshly whitewashed. Welldressed ladies and gentlemen in smart suits pass up and down the streets.’

Surprisingly, perhaps, the pragmatic Taine’s most positive comments on Scotland were reserved not for its glorious scenery or for the architecture of its cities, but for the pleasures of this ‘lively and attractive modern town so near the extreme of Scotland, on the flank of the wild Highlands.’

In these turbulent times in which Scotland’s relationship with Europe is under the spotlight, Taine’s respectful fondness for Scotland might be a lesson to us all.

TAGS