Marking a Scot’s centenary of bravery in World War I

With the centenary of World War One upon us this year, the National Army Museum is marking the occasion by highlighting the stories of inspiring Scottish soldiers, including that of Aberdeen’s Captain William Leith-Ross.

A fitting example of the bravery and endurance demonstrated by the British soldiers, Captain Leith-Ross was a member of Dunsterforce, and shed light on this largely unknown episode through his photographs and papers.

The son of John Leith-Ross, laird of Arnage Castle near Ellon, Captain William Leith-Ross was born in 1884 in Meerut, India and after completing his education was commissioned as a second lieutenant on the Indian Army’s Unattached List in January 1904 and posted to second Battalion The North Staffordshire Regiment in Dugshai. Continuing his service first in the 77th Moplah Rifles in Bangalore, he later joined the 55th Coke’s Rifles (frontier Force) in 1907. He married Elizabeth Martin Stewart in 1914 and had two children.

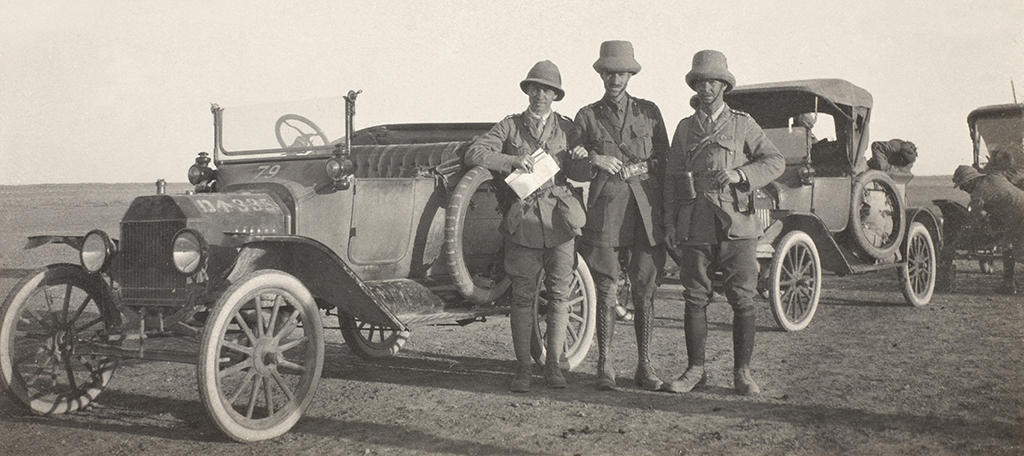

Captain William Leith-Ross (centre) with two colleagues during the Jezireh Reconnaissance, March 1917

Leith-Ross went to France in October 1914 with 57 Wilde’s Rifles (Frontier Force) where he served as a company commander and then a staff officer at the Ferozepore Brigade headquarters. He was present at La Bassée, Messines and Givenchy in 1914 and Neuve Chapelle and the second battle of Ypres in 1915.

He was also linked to the intelligence staff of the Indian Expeditionary Forces headquarters in Mesopotamia and went on to produce reports for the British high command. This role gave him the chance to survey and report on the British area of operations and his photographs resulted in two remarkable albums now in the museum’s collection.

Given his intelligence experience and the fact that he was already in theatre, Leith-Ross was an ideal recruit for British special operations unit Dunsterforce and he was seconded to Dunsterville in January 1918.

This handpicked team of soldiers undertook a courageous secret mission to northern Persia (now Iran) and the Caucasus, with the aim of unifying the various anti-Bolshevik and anti-Turkish groups fighting there into an effective force.

After the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia during the October revolution of 1917, Dunsterforce were sent in to protect Baku’s oil installations and the strategically important Trans-Caucasian railway from the Turks and Bolsheviks. This would also secure the eastern flank of the British forces fighting in Mesopotamia, now exposed following the withdrawal of the Russians.

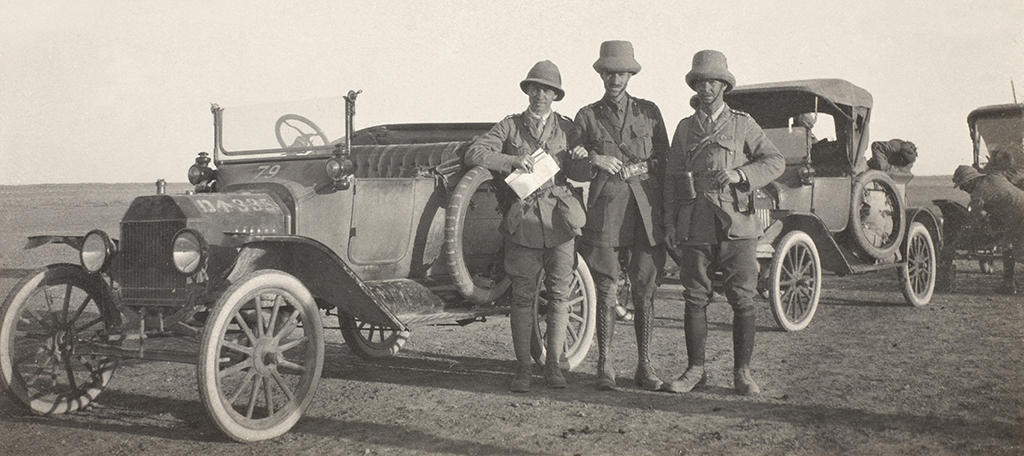

William Leith-Ross talking to a visiting dignitary shortly after landing his aircraft in Mesopotamia, April 1919

The unit comprised some of the British Empire’s most impressive men who demonstrated traits of tough character and strong leadership. ‘All were chosen for special ability and all were men who had already distinguished themselves in the field. It is certain that a finer body of men have never been brought together’, said major General Lionel Dunsterville, whom the unit was named after.

The team’s endurance was thoroughly tested throughout their mission. They often had to work in hostile environments plagued with famine, war, genocide and civil unrest. Leith-Ross and the rest of the unit assisted these areas by training local militants in the protection and defence of their villages against the enemies.

Challenges continually tested the unit. When they made it to Baku in July 1918, they were welcomed by 7,000 volunteers from Armenia, Assyria and Russia who were working together to protect the city. Dunsterforce struggled to strengthen and reinforce the new fleet and were left feeling unprepared for the looming battle in Baku from August to September 1918.

Leith-Ross noted his frustrations with the other volunteers, writing: ‘The Armenians instead of holding on to the Bingardy position fled at the final attack’.

Witnessing Armenian women fighting in the trenches, he observed: ‘There were many women who did this, for they had lost their homes and had nowhere else to go. They preferred to take their chances with their own men, rather than remain behind unprotected.’

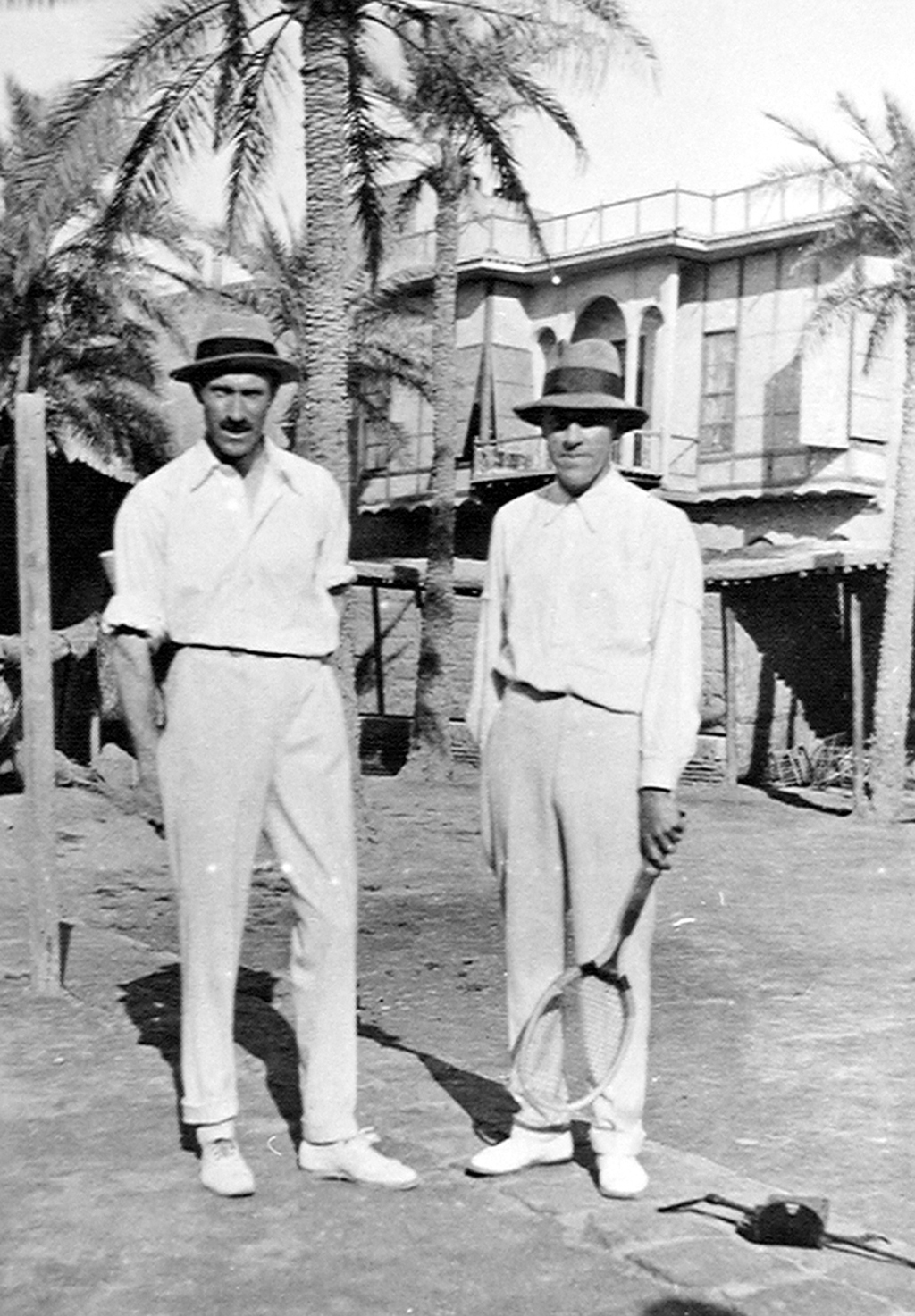

Major William Leith-Ross with Norman Brookes at the final of the Mesopotamia Tennis Championship, in 1918

Recurring issues like this meant that Dunsterforce were unable to secure the oil refinery or the port. Due to lack of resources, both in terms of manpower and equipment they also failed to establish a base for recruiting and directing irregular forces.

Dunsterforce were evacuated from Baku back to northern Persia in September 1918 and the War Office disbanded the unit. Despite not achieving all of their objectives, the unit exhibited tremendous courage and hard work, which was undoubtedly difficult to maintain during the extreme temperatures they endured, which rose as high as 50 degrees Celsius and fell as low as -40 degrees Celsius.

Leith-Ross was gazetted full captain on 3 June 1918 and awarded the Military Cross for his exploits in the Caucasus. After this, he returned to his intelligence duties with the Expeditionary Force, remaining in Mesopotamia until the end of the war.

A keen sportsman, in 1918 he successfully reached the final of the Mesopotamian open tennis Championship where he lost to Norman Brookes, the 1907 and 1914 Wimbledon champion, another impressive achievement for Leith-Ross.

After 32 heroic years in the service Leith-Ross retired from his position of lieutenant-colonel and returned to Scotland. On his return in 1936, he worked his way up to director of prisons and borstals and the following year he sold his ancestral home, Arnage Castle, moving to Moungan in Ellon before taking his well-earned retirement in 1950.

A member of the Royal Company of Archers, Lieutenant-Colonal Leith-Ross passed away on 5 October 1960 in Aberdeen. One hundred years following the hard work and bravery of Leith-Ross and the other men of Dunsterforce, it remains as important as ever that his story continues to be told.

TAGS