Next stop: St Andrews – why a rail link is needed

There is a compelling argument for restoring the rail link to this popular university town.

Famous around the world as the home of golf, St Andrews boasts one of Britain’s best universities and features in Scotland’s top ten tourist destinations.

It also has the unfortunate distinction of being the only university town in the country without a railway line.

The recent return of the Borders railway in 2015 captured the public’s imagination, with busy daily services. The reopening of that line after almost half a century has rejuvenated calls to fill missing links elsewhere, particularly in St Andrews, where this summer’s quinquennial staging of The Open highlighted a strain on the town’s infrastructure, particularly the roads.

While the Borders was the largest area of the UK without a rail link prior to the much celebrated reopening of the line after a 45-year hiatus, St Andrews is arguably Scotland’s most ‘important’ town, in terms of tourism and economic significance, without such a connection.

But far from watching the £300 million development of the Borders railway with bitter resentment, the opening of the longest new domestic railway to be built in Britain for more than a century was welcomed by campaigners in Fife.

‘What they’ve done is brilliant and an inspiring example for us – it demonstrates what is possible,’ insists Jane Ann Liston, convenor of the St Andrews Rail Link Campaign (STARLink), which has been calling for a link to connect St Andrews with the East Coast line.

‘It shows that if 30 miles of railway can be laid, then so can the mere five miles needed to reconnect St Andrews, a major tourist destination, economic generator, Home of Golf and Scotland’s oldest university town. ’

The only university town in Scotland that can’t be reached by train, St Andrew’s lost its connection to the national network in 1969 – the same year the Borders line closed.

While the Borders fell victim to Beeching’s infamous hatchet report, which brought about the end of hundreds of branch lines across Britain, the line into St Andrews was axed by British Rail; the national organisation deeming the line no longer viable due to a drop in passengers thanks to the rise of the motor car.

Fifty years later and St Andrews, one of the country’s flagship destination towns, remains cut off from the network.

Many students, golfers and visitors heading to the historic town by public transport are surprised to learn that they have to get a bus or taxi from Leuchars station, some five miles away. The bus service is frequent, but the change adds time and inconvenience to the journey, particularly for those travelling with a term’s worth of luggage, while taxis constitute more expense.

Many choose to drive instead – the University of St Andrews sends cars all the way to Edinburgh Airport to collect visiting academics, as it is not considered appropriate to ask them to take a train to Leuchars then change to a bus.

The town’s infrastructure is buckling under the weight of the increasing pressures placed upon it; roads quickly become congested and the town’s attractive medieval aesthetic is often blighted by cars spilling out of car parks and dumped in every available nook and cranny.

Ironically, the increased use of cars – the very reason the line was shut half a century ago – is now one of the main reasons that decision should be reversed.

Since the railway closed, the term-time population of St Andrews has almost doubled, with the number of permanent residents increasing from 9,500 to 14,000, and 7,000 students today compared to just 2,000 in 1969.

Daily commutes into the town also add extra strain – with employment mainly limited to tourism and education, many St Andreans work elsewhere, travelling every day to places such as Dundee, Cupar, Kirkcaldy or Edinburgh. More still commute the other way, with expensive house prices in the town forcing workers to live elsewhere and travel in every day.

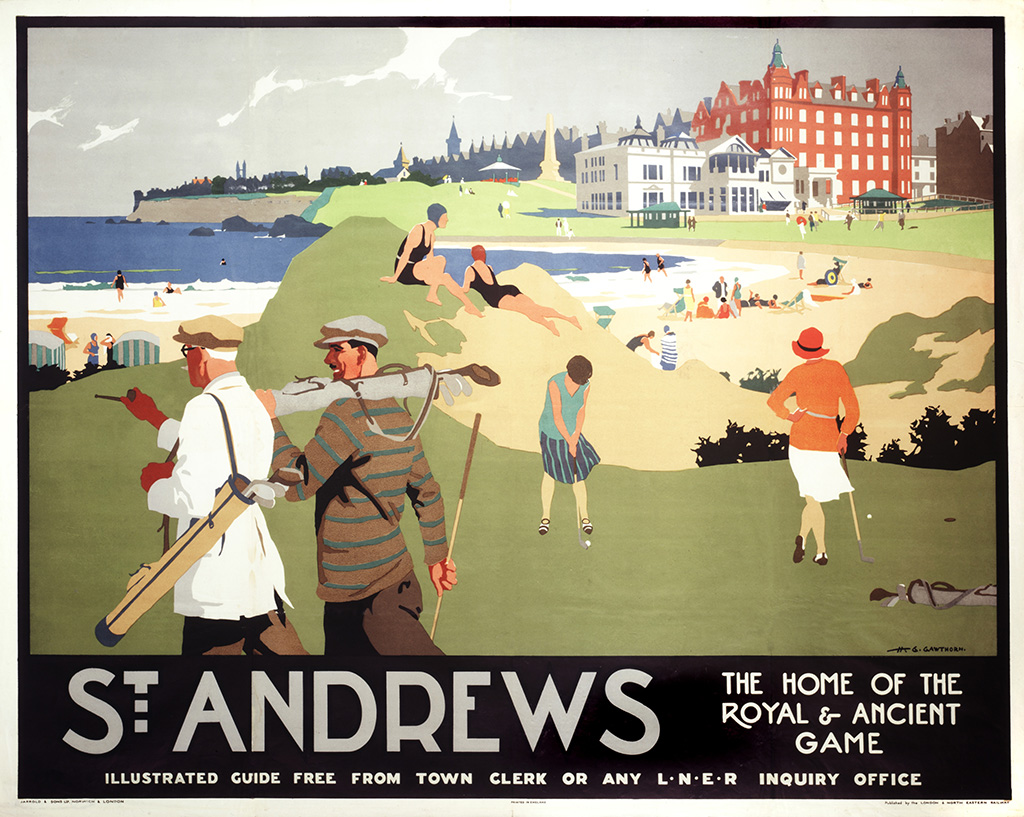

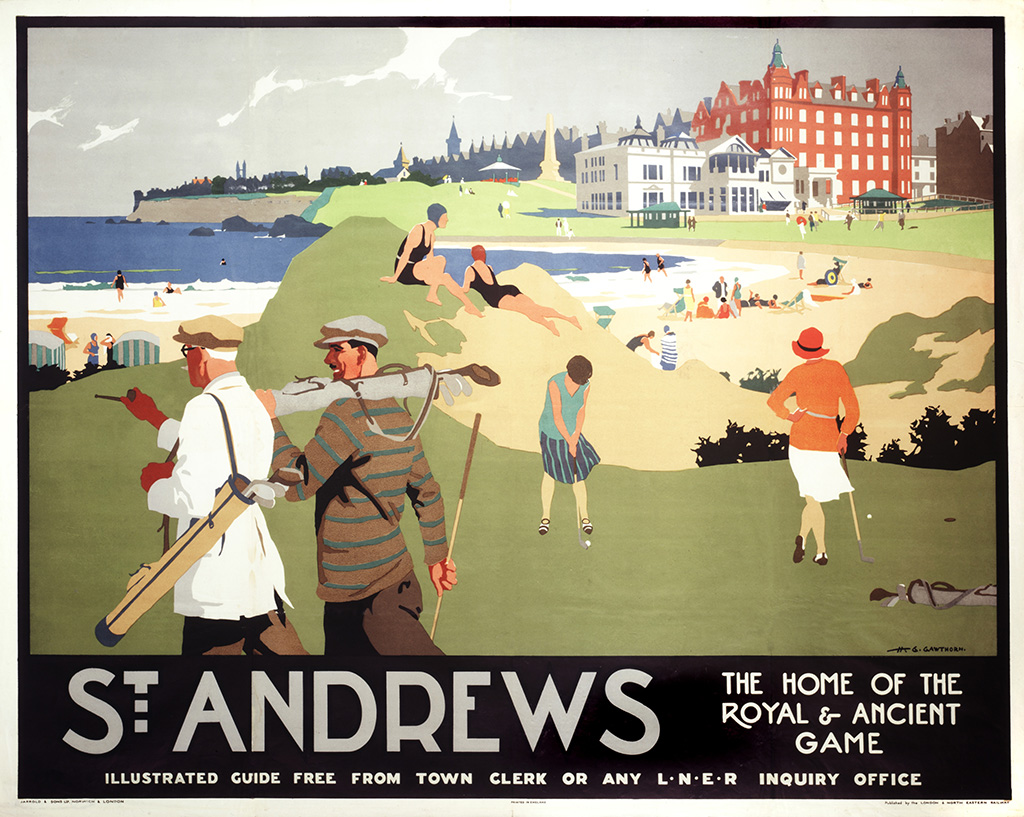

A poster advertising St Andrews, produced by the LNER

Calls to re-establish a rail connection date as far back as 1989, when the chair of the Scottish Tourist Board expressed his concerns to the district council following The Open, and asked whether the railway could be re-established to help the town cope with such large events. Since then The Open has grown significantly.

Add that to St Andrews’ growing student numbers, net import of labour and its attraction as a major tourist destination, and it’s more important than ever to facilitate a rail link.

While the Borders line was rebuilt along its original path, sceptics of a similar scheme at St Andrews argue that much of the old route is now covered by farmland, with the five-star Old Course Hotel occupying a section and a car park sitting on the site of the old town centre station.

But a study carried out by Tata Steel Projects in 2012 identifies an alternative eight kilometre route following the Eden Valley, with a suggested timetable including hourly services to Edinburgh and Dundee, taking one hour 19 minutes and 22 minutes respectively.

The route would include stops at Cupar, Dunfermline and Edinburgh Airport, thus benefiting the wider economy in Fife. Direct trains to and from the airport would impact tourism for the better, while employment opportunities in St Andrews would become more accessible to struggling communities elsewhere in the county.

Cupar’s rail services would be doubled for example, while commuting to St Andrews from Dunfermline would become more viable, with journey time cut by a third.

An efficient method of transporting large numbers of people in and out of St Andrews is needed to complement the tourism offer while alleviating traffic congestion, reducing car-generated pollution and easing the overall strain on the system, while injecting further life into the economy. Car-drivers are notoriously reluctant to use buses, but they will use trains.

It’s astonishing the St Andrews rail branch was closed in the first place; an unbelievably short-sighted decision, even with the benefit of hindsight.

The Tata Steel feasibility study and revised track alignment provide an excellent basis for the reinstatement of a St Andrews line, and with an estimated price tag of £76 million, a fraction of that spent in the Borders, surely it must be re-established soon?

(This feature was originally published in 2015 – since then the Scottish Government has funded a study to look at the scheme)

TAGS