As many of us consider replacing our gas-guzzling cars with eco-friendly alternatives, Robert Davidson was an Aberdonian who pioneered the idea of electric transport back in the 19th century.

It’s funny how things have a way of coming back into fashion: vinyl records, beards and the wonderfully nostalgic Polaroid camera.

But perhaps the most significant piece of technology to stage a comeback is the electric car. We realised the catastrophic effects petrol and diesel cars have on our environment a long time ago, and the search for alternatives to our pollutant-heavy motors led us back to the very beginning.

From the mid-19th to the beginning of the 20th century, a burgeoning electric car industry was taking shape around the world. They were cheap to run, easy to drive and reliable. While the UK and France were the first to support the widespread development of electric cars, the US became the country where they were most widely accepted. They became so popular that towards the end of the 19th century, both London and New York each had a fleet of electric taxis.

However, by the 1920s, discoveries of petroleum reserves across the world increased the affordability of gasoline-powered vehicles which could cover much greater distances at higher speeds and electric cars all but disappeared from the automobile market.

With a view to safeguarding the environment for generations to come, the electric car industry is once again in the fast lane, bolstered by a target set by the Scottish Government to end the sale of petrol and diesel cars by 2032.

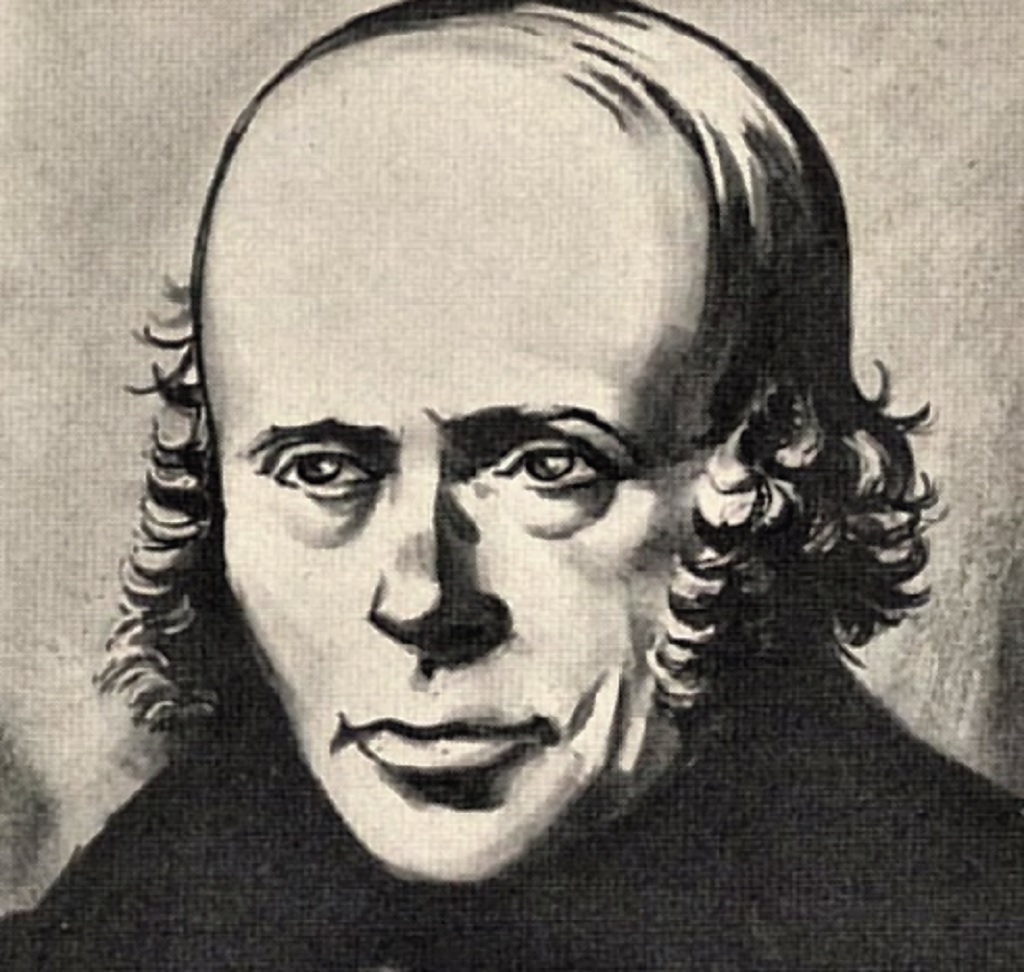

Robert Davidson

As we consider the latest models and even admire a growing range of electric supercars, it’s worth looking back at one of the pioneers who ‘turned the key’ and unlocked the potential for transport powered by electricity.

Born in 1804 in Aberdeen, Robert Davidson was the son of a grocer and wine merchant. He attended Marischal College from 1819-1821 before setting up a business supplying yeast from premises at Causewayend and in nearby Canal Road, close to the Aberdeen-Inverurie canal. Davidson moved on to chemical manufacturing and supplying but his real passion remained with electricity.

Davidson began to construct his own batteries and by 1837 he had made his first electric motor. As this was during the height of the stage and mail coach era – before the laws of electricity were understood or written, and before there were any units of electricity introduced – it truly was ground-breaking work.

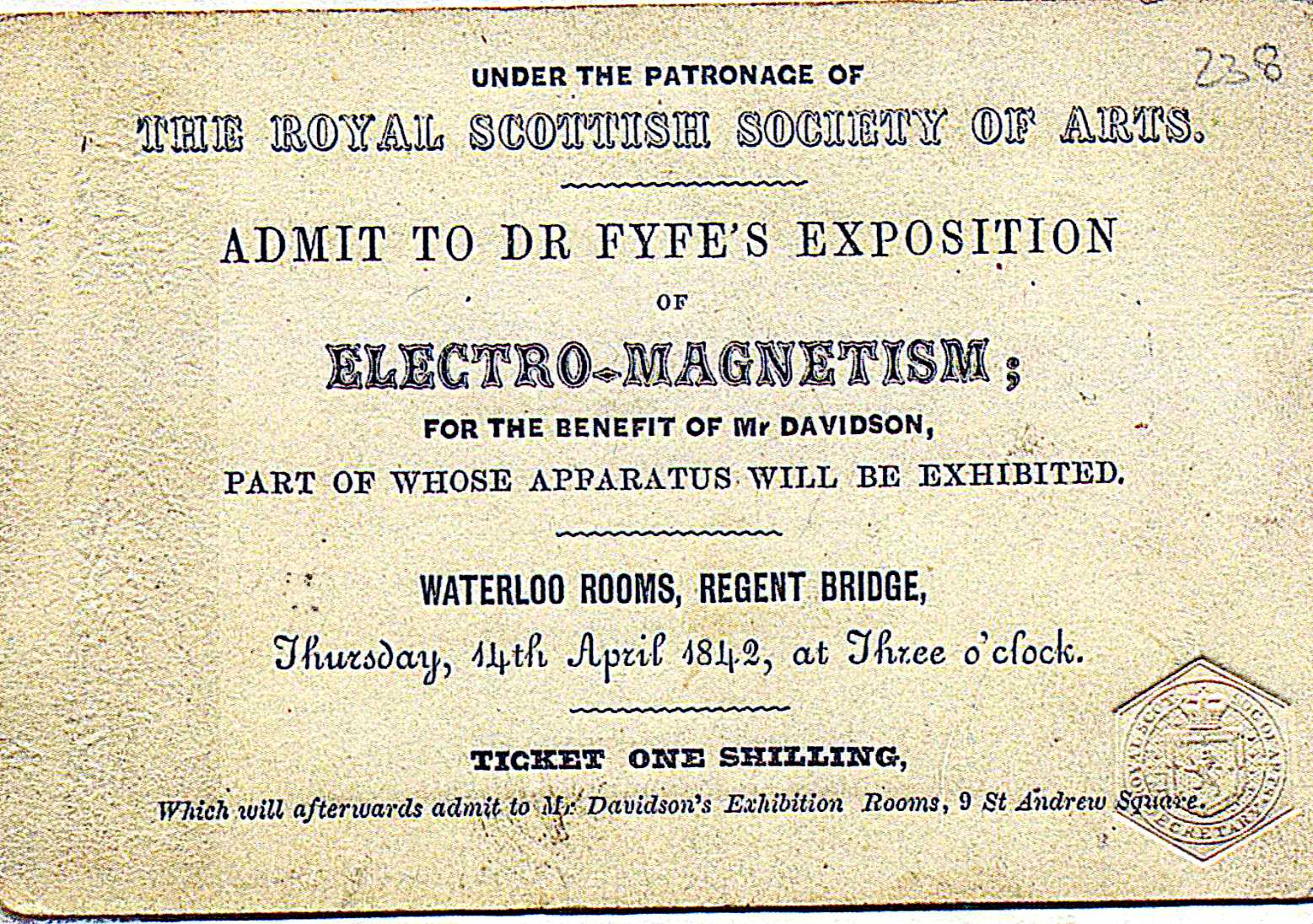

Two years later he held an “Electromagnetic Exhibition” in Aberdeen to showcase his model electric locomotive which could carry two people. Visitors paid to see this along with a model electric lathe, a small electric printing press and an electro-magnet that could lift two tons when supplied by a suitable battery. While these creations were classed as ‘models’, both the lathe and the printing press’ motor had a 5ft diameter flywheel.

Reporting on Davidson’s work, The Aberdeen Banner prophesised that electromagnetic machinery “will in no distant date supplant steam”. The year after his debut exhibition in Aberdeen, he took his innovations to Edinburgh where a young James Clerk Maxwell and his father saw them.

In a bid to attract the necessary funding to develop his technology, Davidson travelled to London and by this time he had built a full-sized prototype electric locomotive called Galvani. It was 16ft long and weighed about six tons. In 1842, it ran at four miles per hour on the Glasgow to Edinburgh line.

Sadly, there were those who felt unsettled by the prospect of steam engines eventually being replaced and a group of men destroyed the Galvani. Davidson’s efforts to secure a patron to finance his work weren’t effective meaning he was not in a position to make electric railways a commercial success as he lacked both the funding and suitable technology.

The chemical batteries which provided the power for Davidson’s machines were expensive and to re-charge them the chemicals had to be replaced. It wasn’t until 1859 that the re-chargeable lead-acid accumulator was invented by French physicist Gaston Planté.

Fast forward to the 1890’s and the electric locomotives were now making city underground railways a possibility and the electric car was a common sight on the streets of a number of cities across the world.

At this point, an elderly Robert Davidson was ‘discovered’ by the media and turned into something of a celebrity. He was described as an “Octogenerian Aberdonian – the oldest living electrician” and The Electrician magazine reported that ‘Davidson was undoubtedly the first to demonstrate the possibility of electrical traction in a practical way.’

If only Davidson had found a willing financier who recognised the potential of his work in the 1840s – the journey of electronic transport could have gained momentum much sooner.

A long-standing exhibition at the Grampian Transport Museum tells the story of electric vehicles with a key focus on Robert Davidson’s role. It’s electric – which opened on 30 March 2017 – also looks to the future and even features Davidson’s great-great grandson Stuart Scorgie who plays the part of Robert in a video exhibit.

A book, ‘Robert Davison Pioneer of Electric Locomotion,’ detailing his work was also launched at the opening of the exhibition.

With petroleum and diesel cars being phased out and experts claiming that electric cars will become the norm within five to ten years, it would appear that Robert Davidson, a chemist from Aberdeen, was even further ahead of his time than he will ever know.

TAGS