Facing his fear has made Jules a free solo climber

Jules Lines’s calm head and careful planning has made him Britain’s most accomplished free solo climber.

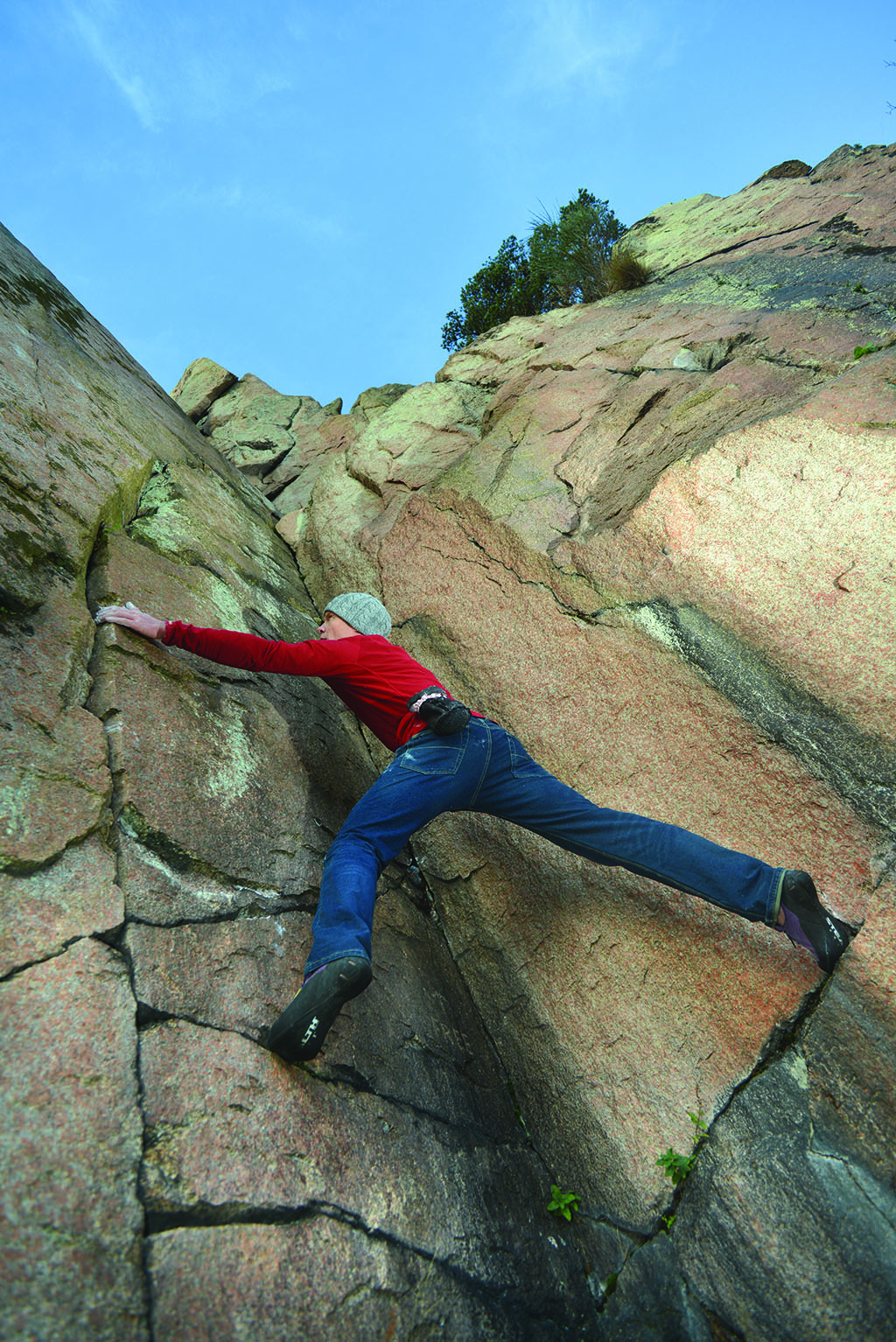

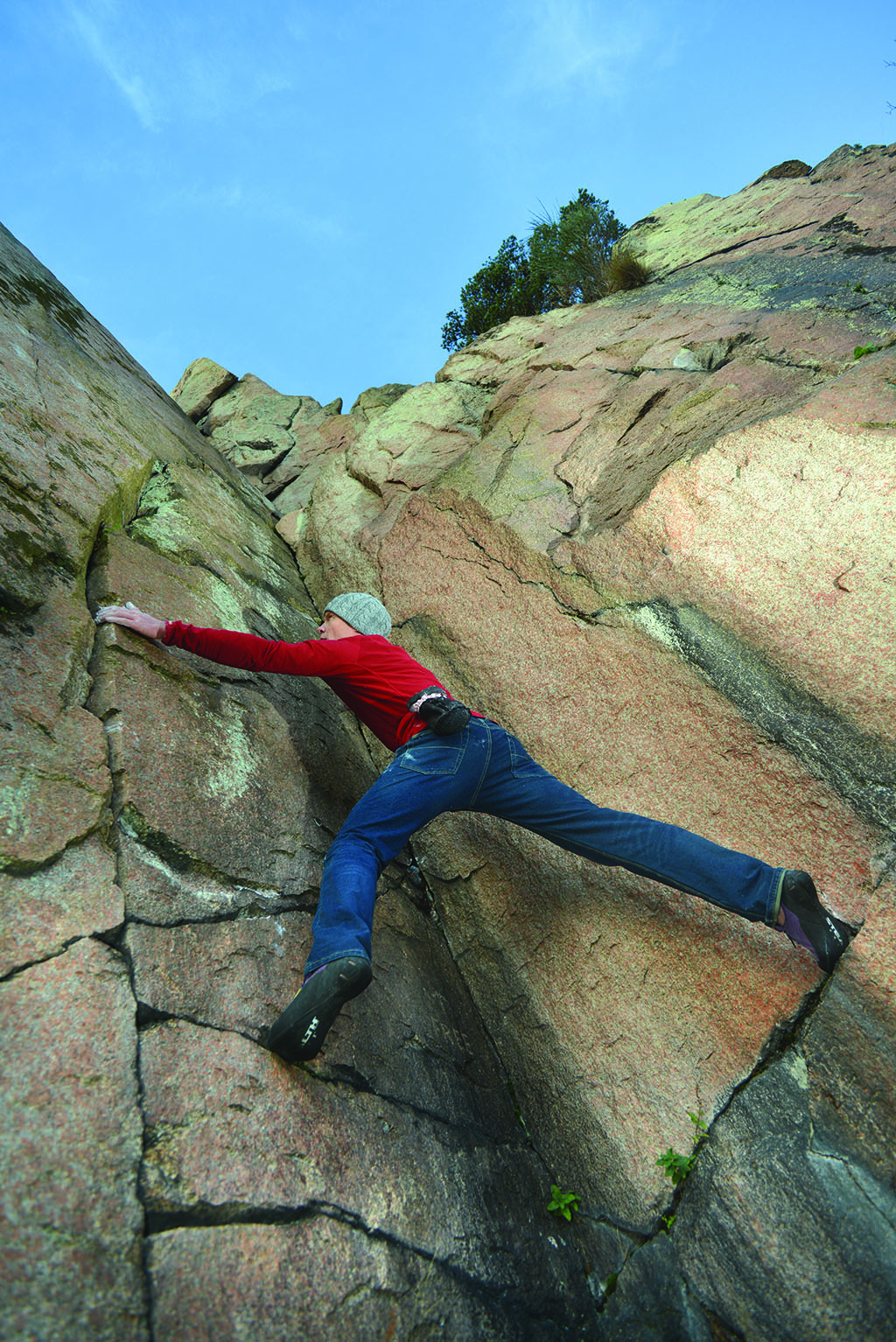

We were about 300 feet above the Pass of Ballater and Jules Lines was posing for photographs, standing nonchalantly on the edge of a sheer cliff like a mountain goat. Lines is one of the UK’s best free climbers, or soloists, which means that he climbs without the use of ropes, often on sheer cliffs with just the tiniest of holes for his hands and feet to grip.

I readily admit that I was expecting to meet an adrenaline junkie, a fearless psychopath with a gung-ho attitude and an in-built deathwish.

What I found instead was someone for whom fear was crucial to his survival, someone who prepared meticulously and was always in control of both his body and mind. He is also a man with a deep respect and passion for the natural beauty of the places he climbs.

Lines was born in Lisburn, near Belfast in Northern Ireland. When he was a year old his family moved to York, and he spent six or seven years at prep school in North Yorkshire. ‘It was there that I really got into the outdoors’, Lines explains. ‘Walking in the Dales, the Three Peaks and summer camps in the Lake District.’

He chose Gordonstoun to board because that’s where one of the old boys who came along on one of their walks had gone. ‘He had a big rucksack with an ice axe on the back’, recalls Lines. ‘I remember thinking, “Oh yes, I want one of them, I want to climb mountains”.’

At Gordonstoun he got into hillwalking and completed all of the Munros whilst still at school. ‘For my 14th birthday, I bought myself a copy of Munro’s Tables. I knew the name and number, and height in metres and feet, of every single Munro.’

Jules Lines indulging in his love of free solo climbing (Photo: Angus Blackburn)

Lines then graduated to rock climbing but, with no-one to climb with, he spent a lot of the time soloing, climbing harder and harder each time.

‘It also satisfied both the part of me that loved climbing and the part of me that enjoyed the solitude,’ says Lines.

Whilst all forms of climbing require physical strength, soloing requires an added degree of mental strength. ‘It’s the difference between walking down the street with your clothes on and without your clothes on,’ says Lines. ‘The famous German climber Wolfgang Gullich – the stunt double for Sylvester Stallone in Cliffhanger – said that the mind was the most-important muscle. When you climb with ropes you can climb a lot harder but there’s a real vulnerability to soloing. The hardest thing is controlling the fear, because if you let fear control you, your muscles are useless.’

Lines himself has been able to trick his mind in what he calls ‘a dangerous game of self-deceit’ by covering the rocks beneath a climb with moss and bracken. He also talks a lot about being in ‘the zone’, which, for him, is about having a bubble around him whilst he climbs. All he focuses on are the holes directly above and below and, if you have the strength, ‘you have a dogged determination to carry on; you’re in your own space’.

Lines is 44 years old and has been soloing for 25 years. One of the secrets of his longevity is constant risk assessment. ‘I have come to

realise that, subconsciously, I am probably the greatest risk assessor on the planet,’ he laughs.

‘You have to choose your rock carefully and assess every move before you make it. You have to work out whether or not you could downclimb if you get stuck at a particular section – it definitely isn’t gung-ho.’

Indeed, Lines once decided to climb down 150 feet from a route on the Three Sisters in Glencoe – a mere two feet from the top – because he wasn’t sure of one of the moves. Of course the fact is that even with the best preparation soloing is dangerous.

Whilst Lines doesn’t know anyone close to him who has died, a number of the top free climbers have perished over the years. Amongst these are John Bachar, who died after falling in California in 2009; in 1993 Derek Hersey died in Yosemite; and in 1987 Jim Jewell died after falling in Wales.

Sometimes conditions conspire to make things difficult. Moisture, ice, wind and rain are all potentially lethal, but Lines believes that the biggest threat to soloists is complacency. ‘One of the top climbers, Johnny Dawes, said that if you know you’re going to die then you’re in the safest place. What he meant was that when you are on the hardest climbs, you are one hundred per cent alert – but on an easier climb, if you’re not concentrating, you can come unstuck.’

Jules Lines has written about free solo climbing (Photo: Angus Blackburn)

Ironically, perhaps, his worst-ever accident was in a paraglider, when he fell 120 feet. ‘I thought I was about to die, so I just relaxed into it – it felt quite peaceful.’ Again, to the amazement of the paramedics, Lines escaped with no broken bones.

As well as mental strength and risk assessment, planning and technique are also crucial for soloing. Lines is renowned for his technique. ‘I am known as a bold technician,’ he explains. ‘When I take on a climb, I try to read the rock, work out where my body needs to be, where my feet will go. I work out where I can rest and think about the next section. I’m always thinking ahead. In fact, it’s much like dancing, except on the vertical – it’s about getting the sequences right.’

And it can often take Lines weeks, even months, to get the sequences right. Last year he completed a route in Glen Nevis, which took him months to work out the most efficient sequence.

‘Once I’d worked it out I had to drop my weight to under ten stone, because the holes were so small I was actually puncturing my fingertips on the rock. I could only climb for a couple of hours, then I’d have to rest for three days.

‘For me it was the equivalent of training for an Olympic final. It was the hardest route I am ever likely to do.’ The route – which Lines named ‘Hold Fast Hold True’ – has been graded an E10 (the British grading system only goes up to E11), which probably makes Lines one of, if not the, best climber in Britain. However, he doesn’t look at it that way.

‘Competitiveness is not in my nature. For me, soloing is about solace, just me and the world around me.’

Jules Lines was schooled at Gordonstoun (Photo: Angus Blackburn)

This love of nature shines through in his book, Tears of the Dawn, which was published last year. The idea started ten years ago, after a couple of articles he wrote for a mountaineering magazine were well received. The book is well written, and his vivid description of the places he climbs make this a lot more interesting than the average climbing book.

Lines has climbed all over the world – in South Africa, Namibia, Spain and Brazil – but Scotland is his favourite place to climb, articularly the Cairngorms. ‘That’s why I chose to live here,’ says Lines, who lives near Aboyne.

‘The Shelterstone, for example, is a special place for me. But Scotland in general is so secluded and peaceful and there are a number of climbs I want to do some day, many of which no-one knows about.’

Lines has certainly quashed my preconceptions about the nature of soloists. He is meticulous, controlled and yes, brave, but certainly not fearless. However, he did admit to being a bit of an adrenaline junkie. ‘It is definitely like a drug to me.

I think it harks back to when we were cavemen – you needed that adrenaline if you were going to stalk a lion, for example. I need the adrenaline rush that I get from feeling fear.’ Well, from what I’ve learnt about Jules Lines, if he was a caveman I wouldn’t bet on the lion.

- This feature was originally published in April 2014.

TAGS