Remembering the custodian of Torridon

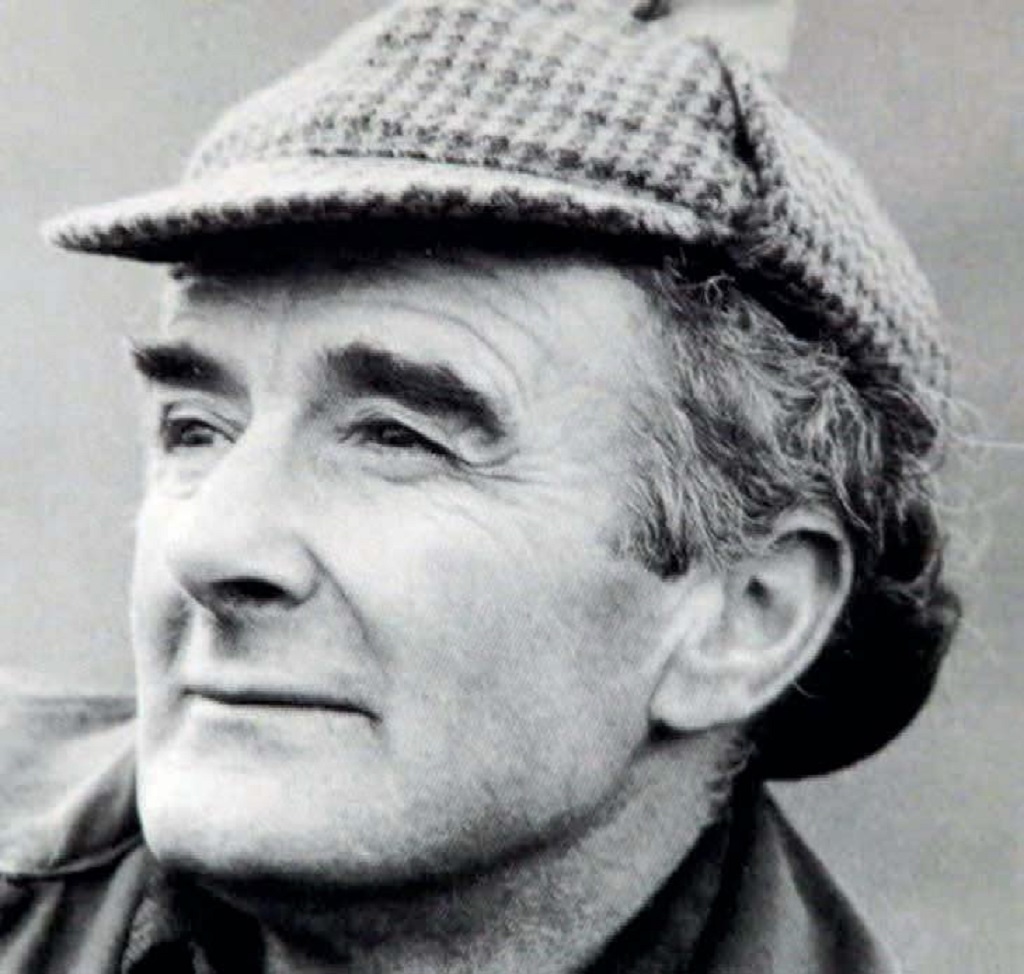

The custodian of Torridon Stalker, author and photographer Lea MacNally’s deep love of our natural heritage – and red deer in particular – has left an indelible mark, inspiring many.

I was recently at Torridon enjoying the deer museum, its intriguing old photographs, anecdotes, antlers and artefacts.

I have been fascinated by red deer since we moved to Ardnamurchan during the 1960s.

My stepbrother and I were avid followers of the writings of stalker and ranger-naturalist Lea MacNally who looked after Torridon for the National Trust for Scotland for 21 years.

His books, in particular Highland Year and Highland Deer Forest, besotted us both. The museum was largely his creation.

When Lea’s brother Hugh became our stalker, my early fascination turned to passion; I frequently begged him to let me accompany him on the hill. When occasion allowed him to take a slow yet keen companion, his patience and kindness was outstanding; never once did he show annoyance at having to drag a child along too.

Lea MacNally spent hundreds of hours annually stalking red deer with only a stick, telescope, camera and notebook

Lithe and fleet as a greyhound, his was the typical lengthy gait of the true hill man and he strode effortlessly over Ardnamurchan’s steep terrain while I struggled to keep up. Like Lea, he had a love and respect for all wild creatures. His was a field knowledge acquired from a lifetime spent in remote places and in particular his formative years at Fort Augustus.

Shy, quiet and unassuming, the buffeting sea breezes frequently carried his almost whispered stories away so that I had to break into a fast trot to keep up for fear of missing anything. Trusted early influences are the means to a firm footing for the soul; during my time at Gordonstoun, the family connection with the MacNallys was further renewed.

We were on expedition to climb Torridon’s vertiginous bastions, Beinn Eighe and Liathach. One evening, keen to meet author Lea, I wandered from our camp to The Mains. When I mentioned Ardnamurchan and his brother Hugh, he treated me like a long-lost friend, showing me the deer park where his tame deer together with their owner had become ambassadors for their kin. Lea was a great storyteller; his anecdotes delighted the droves of visitors that came to Torridon.

I was fortunate to see Beauty – a tame hind that Lea was devoted to. As the nights grew short and the Torridon hills blustered into their more intimidating autumnal mood, the call of the rut grew irrepressible. Lea let Beauty free to find a stag. Like all deer she was strongly hefted to her birthplace and always miraculously returned, though sometimes the wait made her owner edgily anxious. One year she surprised him by having difficulties calving – an unusual occurrence in red deer. He was worried that she had become immense, and joked about the possibility of twins.

Having spent an agonising time battling to help her, a large stag calf appeared, which we assumed was dead. But despite the long and painful haul, he was still alive. With Beauty temporarily disinterested due to shock, Lea rushed to the calf ’s aid before her strong mothering instincts kicked in. Then Lea saw another hoof emerging from his hind. Astonished, he checked that the stag calf had four legs. Beauty went onto rear both a stag and hind calf without further assistance. Lea was only the second eyewitness to have seen this rare event, something he viewed as a momentous privilege.

Lea MacNally looked after Torridon for the National Trust for 21 years

Both MacNallys were of the old school, with clear-cut views on cervine matters. ‘Stalking is the best management tool that we have to ensure that our native wild red deer do not increase in numbers to the extent that they do themselves disservice in eating out, or otherwise damaging their habitat,’ Lea wrote.

He shunned the oft-used expression ‘natural mortality’ and said it was a euphemism for starvation. ‘The dearth of grazing in the long winter and early spring is the critical factor which our native red deer have to face annually,’ he wrote. ‘Deer, mainly red deer, have been my joy, my hobby, my obsession for practically all of my life.’

He spent hundreds of hours annually stalking them with only a stick, telescope, camera and notebook, while his photographs were recognised as some of the country’s finest wildlife images of the era. Indeed, they still compete with the best today, particularly when taking into account his limited equipment. His unsurpassed fi eld craft and photographic skills helped him amass an astonishing photographic library which includes outstanding images of eagle, diver, dotterel, ptarmigan, peregrine, wildcat, pine marten, otter, badger and fox.

A staunch member of the Torridon Mountain Rescue, he claimed to be an unenthusiastic rock climber, pessimistically writing that he felt it was a more or less legitimate way of committing suicide. When watching an eyrie on a treacherous crag through his telescope, he noticed that the female eagle, a bird he knew of old, was behaving strangely. He caught a glimpse of a flash of white. One of a pair of eaglets was trapped in a deep gulley below. He knew its fate was sealed without intervention.

Though it entailed a doubly long walk and two even longer drives, once home he urgently mustered expert climbing friends who returned with him intent on rescuing the eaglet. Their mission was successful despite his sheer terror at being dangled down an impossible cliff face. He was also responsible for replacing stolen eagle eggs into an eyrie on the off-chance that the birds would return to incubate them. Miraculously, one of the eggs did indeed hatch.

His role at Torridon had naturally become that of wildlife custodian and his dedication to the eagle’s welfare was of paramount importance. The esteem in which Lea MacNally was held was recognised when Prince Charles invited him to stalk at Balmoral – with His Royal Highness acting as his stalker. They passed a wonderful day together, though Lea struggled to come to terms with the prince carrying the rifl e and being insistent on gralloching the beast himself. Afterwards he commented sagely: ‘The policy on Balmoral was as mine; bad heads were to be taken as a priority, while any head likely to improve was always to be left.’

When Lea MacNally retired from Torridon, this countryman, who knew red deer and their natural history better than any other, left an indelible mark. He had not only inspired and taught generations of visitors and locals, but together with his wife Margaret had instilled his broad knowledge and symbiotic relationship with the natural world into their sons, Lea and Michael, as well as their grandchildren, nieces and nephews. Forthright and honest and utterly lacking in prejudice, he had a huge following and contributed widely to many publications, including this one.

He remained Scottish editor of the British Deer Society’s Journal until his sadly premature death in 1993. His loss would be keenly felt. But there was another MacNally waiting in the wings. I was still perusing the deer exhibits when he appeared in the doorway. Seamus MacNally, Hugh’s son, was away at boarding school when his younger brothers and sisters were at Kilchoan Primary School with me, and our paths never crossed. There is a distinct likeness to his father – the same quiet voice, his demeanour unassuming yet as deep as Loch Maree.

During the holidays he sometimes accompanied his father on the hill taking my stepfather and stepbrother out. Modest to the point of being self-derogatory, he too has been a lynchpin for the National Trust for Scotland, working tirelessly at Torridon for a quarter of a century.

A staunch member of the Mountain Rescue, he was team leader for six years before stepping down simply because he felt someone else should have the opportunity. A large pied dog lies on the fl oor snoozing whilst we chat. Lui is the second Search and Rescue dog Seamus has trained. His collie-cross-spaniels prove ideal, and together they have been called to many rescue missions in the Highlands, including the Cairngorms, Assynt and Ben Nevis. His stories of visiting his uncle are laced with dry humour.

Lea didn’t learn to drive till late in life and his driving was apparently hair-raising. Prior to that the two travelled together to remote glens by scooter, walking miles in to watch eagles on their eyries, for Lea knew his nephew was also daft about birds.

Prior to his arrival in Torridon, Seamus spent fi ve years on Rum as estate foreman operating the fl it boat before the new pier was built, delivering coal and looking after the island’s Highland cattle and ponies. When the seldom-handled beasts required pedicures, it was often akin to a wild-west rodeo.

In his current role as resident ranger-property manager, much time is spent on the hill. The stalking is not let out and Seamus carries out annual culls. Part of his work involves acting as occasional mountain guide on the notorious triptych of Liathach, Beinn Eighe and Beinn Alligin. There are fi ve Munros on the National Trust for Scotland’s ground. Ironically, like his father and uncle, he is none too partial to heights.

He claims his early career as a London policeman was unsuccessful for he found standing outside the Argentinian Embassy during the Falklands War a dull job, yet clearly he would have been perfectly suited to working in the dog section. But like all the MacNallys, he is modestly knowledgeable, hefted to the glens and hills of the north west. And is the perfect naturalist-stalker to fill his late uncle’s boots.

TAGS