Scotswoman who braved the wilds of Australia

If America’s frontiers were expanded westwards by cowboys and cattle ranchers, so Australia’s interior was also opened up by the bullock drovers.

These days we are used to images of ‘road trains’ in which huge trucks pull multiple wagons bursting at the seams with cattle, but in the nineteenth century, before a network of highways opened up the interior, those beasts were moved on foot – which is why most towns in rural Australia are placed one day’s bullock drive apart.

And, as with America, where many of the early cowboys were Scots, the hardy nation-builders who forged Australia one cow at a time were often Scots.

But the great untold story is not of the Scotsmen who took to this gruelling occupation, but the three Scotswomen who did so.

The most famous of all was Agnes Buntine, a bull of a woman whose feats continue to shape Australia and whose achievements include single-handedly driving a bullock train from southern Victoria over ‘The Great Divide’, or what is now known as the Australian Alps, which is the third-longest mountain range in the world – to the goldfields, 120 miles away.

Agnes holds pride of place in Patsy Adam-Smith’s seminal history, Outback Heroes. It’s an account that tells of an incident in the 1860s, in the Queensland mining town of Bald Hills, when someone took a bull-whip to a man who had ‘pawed’ a young girl, and ‘thrashed him nearly sober’. The dude with the whip wasn’t Clint Eastwood; it was Agnes.

Agnes Buntine was born in Glasgow

Born in Glasgow in 1822, Agnes Davidson went to Australia at the age of 18 in 1840 and worked as a dairymaid, marrying fellow Scot Hugh Buntine, who was from Kilwinning in Ayrshire, that same year. They added six children to the five he had from his first marriage (his first wife had died of typhoid on the voyage out), and headed for the hills of Gippsland in Victoria, where the forests and mountains had defeated many explorers, to carve out a living.

Settled in Gippsland, they ran a pub, the Bush Inn, for three years before opening a general store. Even though Hugh was ill, he ‘began helping the sick and injured and became known as Dr Buntine,’ wrote Adam-Smith. Being an entrepreneurial soul, Agnes decided to start a carting business.

Fast forward 20 years and a man called JJ O’Connor walked, wet and cold, into a pub at Toongabbie, a small country town in south-eastern Victoria on the way to the goldfields, after driving cattle all day. ‘I saw a boiling kettle on the fire, and thought a hot whisky would be fine,’ he said. ‘Just then, in walked this great big, rough-looking woman and the landlord introduced me.’

It was Agnes, and she was wet and cold too.

‘Being the only guests, we sat all evening by the fire,’ wrote O’Connor. ‘She didn’t boast of anything she had done beyond rearing and educating her family. I asked why she took up bullock-driving, and she said she had to keep her family, and as men were making good money at the carrying trade, she thought she could do the same.’

In 1851 Agnes made that ground-breaking journey over The Great Divide. ‘Her cargo was one ton of cheese and half a ton of butter,’ wrote Just then, in walked this great big rough-looking woman and the landlord introduced me to Agnes Adam-Smith, ‘and she carried a rifle. When she arrived, she opened two stores and a third when another gold rush began that saw the local population soar from 23,000 to half a million within six years.’

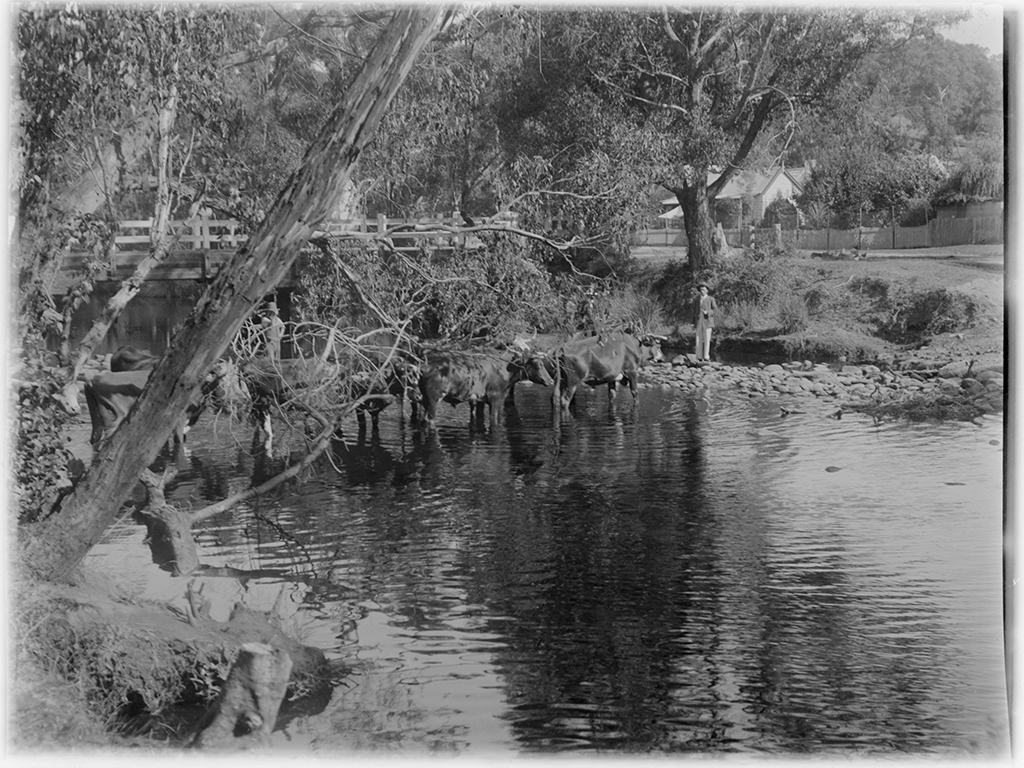

A bullock team crossing a river in 1903 (Photo: Mark Daniel)

Diggers started seeing her as a reliable carrier network between them and Melbourne. They knew Agnes would do it, whatever the weather or terrain. A typical trip from Melbourne was by sea to Port Albert, then bullock train and, finally, packhorses into the mountains. She was often the first to get to places that had been thought to be inaccessible.

As well as handling horses and bullocks, ‘she could ride, kill and dress a bullock’, split timbers and make fencing. She was as at home with a pick and shovel as she was with a whip. They called her Mother Buntine. In 1863 she almost died ‘while fighting to save her wagons and freight from a bushfire’. Six years after Hugh died in 1867, she married Michael Hallett and took up farming.

There were three female bullock-drivers in Australia in this pioneer period, and all were Scots. One did it just to move her six children and household possessions from one place to another after her husband died. Another was Margaret McTavish, who ran away to live with aborigines for a month after her father beat her for not riding side-saddle. He tracked her down and burnt her feet with a hot iron so, when she reached 14 she dressed as a boy, called herself Tommy and became a bullocky’s offsider and horse breaker.

Margaret’s disguise was so good that her father once passed her in the street and didn’t recognise her. When she got injured, people found out she was a girl, but her boss refused to believe it, saying ‘a better chum had never existed’. She gave up that life then, was married and had seven children.

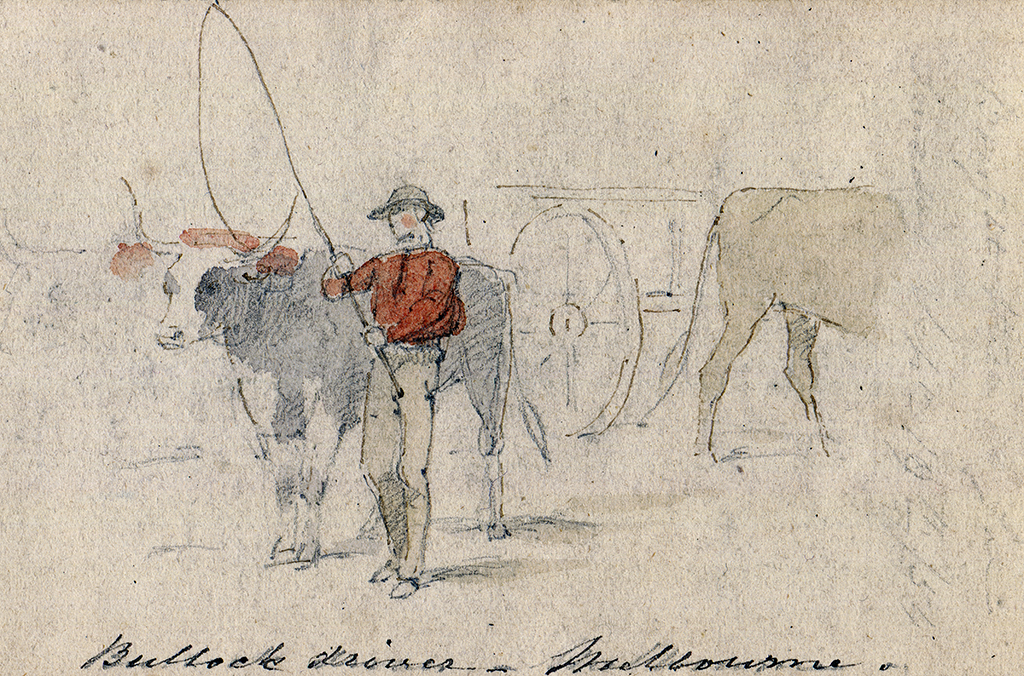

A bullock driver in Melbourne in 1864 (Drawing: William Strutt)

As for Agnes, her carting business went on until her death aged 74 in 1896. But 100 years after Agnes started, out of the blue came another Buntine, her great-great- grandson Noel who, at the same age she had been, started a transport business in the Northern Territory called Buntine’s Roadways.

At a time when cattle were still being moved overland by drovers, he started moving them through the outback by truck. He showed the same staying power displayed by his mother, Iris Buntine, who in 1975 received a British Empire Medal from the Queen for her role as postmistress/telephone exchange operator at Stonehenge in western Queensland for 50 years.

Starting in 1953, Noel moved 3,600 cattle in his first year, and soon had equipment capable of lifting that number in a single operation. Before long Noel was running the biggest road train business in the southern hemisphere, and by the time he sold his business in the 1980s after 30 years in charge, he had 50 road trains, each over 50 metres long, carrying stock in the Northern Territory, northern South Australia and western Queensland.

The fact that many country towns in Australia are placed one day’s bullock drive apart may be lost on today’s Hertz-driving tourists, but for those who drive along in the outback dreaming of the past, there is nothing quite

like a road train overtaking you to remind you of Agnes Buntine.

This feature was originally published in 2016.

TAGS