The 19th century train tragedy of Aberdeenshire

The thrill and controversy that greets today’s proposals for faster rail links between cities across Britain is not new.

In the nineteenth century, the appearance of railways in hitherto highly inaccessible areas of rural Scotland provoked exactly the same combination of excitement and debate. And questions of safety, then as now, were never far from the surface.

In 1846, after a great deal of opposition from rival schemes and a number of technical problems, the Great North of Scotland Railway Company finally received Royal Assent to produce a line that would run from the Northern outskirts of Aberdeen to the town of Huntly.

The idea was that the line would ultimately help to connect Inverness with the railways of the South via Aberdeen. Construction of the railway started at Westhall, Oyne on 25 November 1852.

Huge crowds assembled from all the surrounding districts to watch as Lady Elphinstone, wife of Sir James D. Elphinstone, baronet of Logie-Elphinstone, and chairman of the Board of Railway Directors, performed the ceremonial cutting of the first sod of turf.

Trains became a part of everyday life in rural Aberdeenshire, until Dr Beeching’s report

Opening Verse of ‘The Railway Carol’ by Mr William Cadenhead

(on the cutting of the first turf of the Great North of Scotland Railway)

What ho! Ye sturdy Burghers,

Or by the wandering Dee;

Or where the Ness down its broad firth

Rolls onward to the sea;

Or ye who dwell upon the Don,

Or Ury’s classic shore,

Or ply your crafts with stalward arms

In the borough of Kintore;

Ho! Ye who dwell in Huntly town,

On Bogie’s silver side,

And fling the flashing shuttle

Or tan the tough ox-hide;

Ho! Dwellers in fair Elgin,

Ho! Denizens of Keith,

And ye who won in Forres town,

Beside the ‘blasted heath’;

Rouse up! Rouse up! Ye Burghers all,

Put on your best array-

This day the first turf’s to be cut

Of the Great Northern Way.

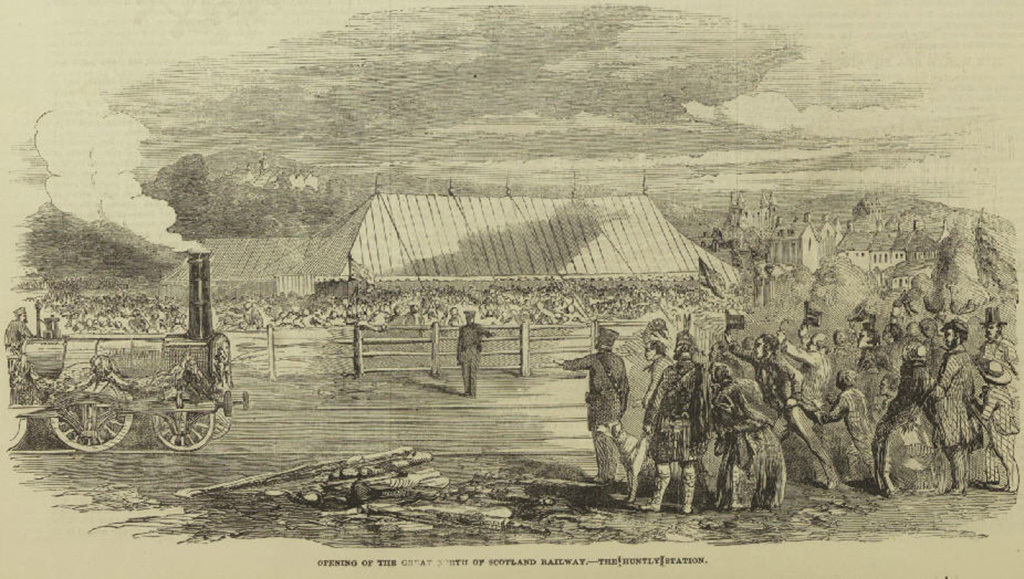

Just under two years later, on 12 September 1854, the line opened to goods traffic. Seven days later, a special passenger train consisting of two engines and 25 carriages started from Kittybrewster station in North Aberdeen at 11 am and arrived in Huntly, Aberdeenshire, exactly two hours later. On board were some 400 passengers (including the directors of the scheme and prominent Aberdeen citizens). Each one had paid one and a half times the ordinary fare for the privilege of travelling that day.

The 40 mile route (consisting of a single track with few stopping places) was thronged with well-wishers including hundreds of schoolchildren who greeted the sight of the train with ‘demonstrations of wonder and delight’. The fourteen stations along the line were all ‘tastefully decorated, though three (Kinaldie, Buchanstone and Wardhouse were not yet finished).

An illustration, showing the opening of Huntly train station

At Inverurie, members of Aberdeen City band, who were accommodated in one of the carriages, struck up. At Huntly, the passengers disembarked and enjoyed a grand banquet in a marquee erected in a field near the River Bogie.

Toasts were made to everyone from the directors and engineers of the company to the landowners and tenants who owned and farmed the land along the track. Nobody was forgotten.

Sir James Elphinstone marvelled at the physical strength of the navvies who had actually cut the track stating that ‘if Lord Raglan (British commander of troops in the ongoing Crimean War) had under his command five or six times as many of them as had been employed on the Great North Line, he would march into Sebastapol in a very short time!’

Sir James Elphinstone’s words were also memorable for other reasons that day. He boasted, that though less ‘florid and ornamental’ than some lines to the South, the new simple Scottish railway would carry passengers ‘at least, as safely to the end of (their) journey.’ Unfortunately, he was to eat his words all too soon.

On 24 September 1854, just five days after the ebullient opening festivities, the congratulatory mood came abruptly to an end. A passenger train of seven carriages, due to depart from Kiitybrewster station at 8.45 in the morning, awaited the arrival of an engine from Huntly. As the south-bound engine approached, the driver failed to stop at the danger signal about a half a mile from the terminus. The engine smashed into the rear end of the train with terrible consequences.

Kittybrewster station and freight yards, before their closure in 1968

On impact, the first (third class) carriage was completely destroyed, the second forced off the line, and the other five pushed up a steep incline. About a hundred people were thankfully able to jump out unscathed with one of them, the local vicar, reporting seeing sticks and debris ‘flying across like juggler’s balls’.

The Aberdeen Journal reported that there was one fatality – a Mrs Stevenson, wife of a ‘stabler’ from West North Street, Aberdeen and ‘the mother of a grown up family.’ Sitting in the third-class carriage, the poor woman had fallen beneath it as it broke up and was killed when the wheels of the engine ran over her. Miraculously, her husband, who was sitting next to her, managed to escape with just a slight bruising to his arms.

60-year-old spinster Agnes McRanald suffered a fracture to the top of her left shoulder. Also injured was Mr Alexander Russell, a saddler from Pitmachie, who suffered internal injuries. Francis Lowrie, a plumber was badly hurt about the head, and a son and daughter of Mr Rust, a local Aberdeen wood merchant, suffered from shock.

One of the few wealthier passengers to be injured was Captain A Lewis, ‘a gentleman belonging to Lloyds’ who was on his way North on shipping business. The injured were cared for in local houses and hotels including Laffen’s and Doyle’s.

Looking along a platform at Fraserburgh towards the remains of the station buildings

Despite the fact that 30 year-old engine driver, Adam Brown, was considered to be very experienced, he was immediately taken into custody along with his stoker ‘Thomson’. The cause of the accident was later put down to driver error together with inadequate track layout, and station staff error. So much for Sir James Elphinstone’s claims about the ‘compact and substantial’ nature of the railway works. It was estimated that this early accident cost the Great North of Scotland Railway Company about £15,000.

The director may have overestimated the safety of the Great North of Scotland Railway, but he did not overstate its importance to the local area.

Two years after the opening ceremony (in 1856) the line was extended in the North as far as Keith. The company also came to an agreement with the Inverness and Aberdeen Railway to meet at Keith and instigate reciprocal running powers from 1858. Meanwhile at the southern end of the line, a ‘Canal Branch,’ running over the route of the Old Aberdeenshire Canal, meant that trains could eventually run as far as Waterloo station in the city (near the harbour).

The simple Northern line never attracted huge numbers of passengers but it did allow for massive amounts of agricultural produce (principally fruit, eggs and animals) to be transported in and out of Aberdeen and to the South, thus achieving what Sir Elphinstone had hoped – that by the railway, ‘this part of the country be raised to the level of other parts of Scotland.’

TAGS