Was Aberdeen the birthplace of Scotch whisky?

Historians have uncovered the earliest ever reference to a still for distilling Scotch whisky – which suggests the origins of the spirit may lie in the thriving renaissance burgh of Aberdeen.

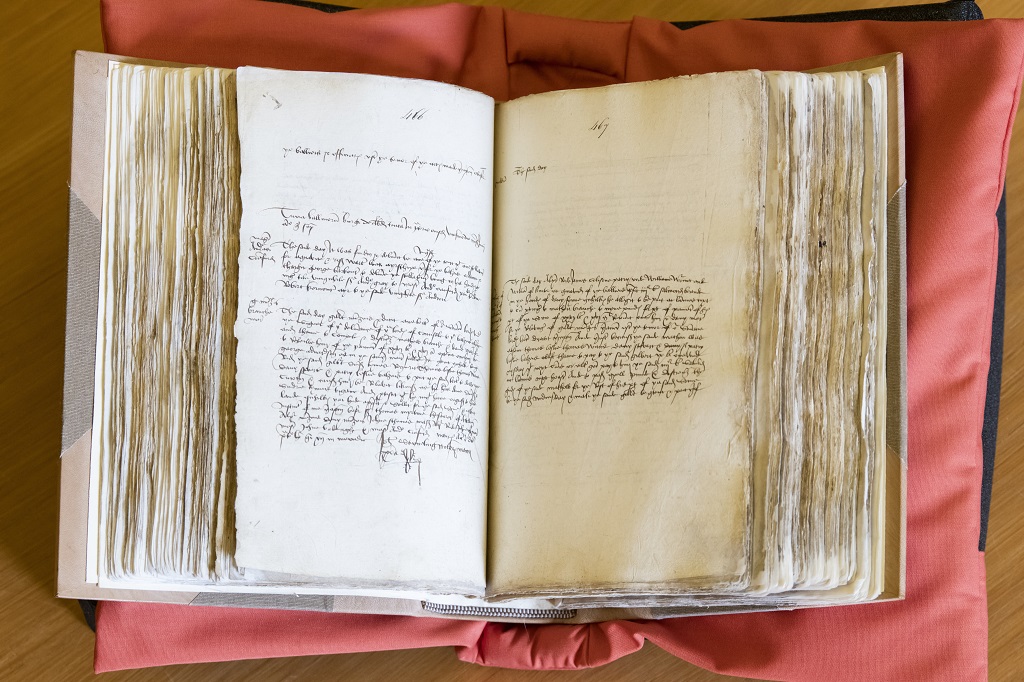

Researchers from the University of Aberdeen came across a 1505 record for a still for making ‘aquavite’, which in Latin means ‘water of life’ and is the Middle Scots word for whisky, in the city’s UNESCO recognised Burgh Records.

It was found by research fellow Dr Claire Hawes who was working her way through deciphering the 1.5million words in Aberdeen’s municipal registers, the earliest and most complete collection for any Scottish town, to make them digitally available in the recent publication Aberdeen Registers Online: 1398-1511.

Although not the first reference to whisky, which is widely recognised as being in 1494 when the king ordered malt to be sent to make ‘aqua vite’, it is the earliest ever found for a still for Scotch whisky and its descriptor suggests this was a spirit to drink, rather than to be used in the preparation of gunpowder.

The reference appears in the inquest into the inheritance arising from the death of Sir Andrew Gray, convened at the bailie court of Aberdeen on June 20, 1505.

Among his ‘moveable possessions’ was ‘ane stellatour for aquavite and ros wattir’. Andrew Gray was a chantry chaplain in Aberdeen’s parish church of St Nicholas, and he was associated with the master of the burgh’s grammar school in 1499. He died in December 1504 and it is probable that he made use of his still during his lifetime.

The University of Aberdeen’s Dr Jackson Armstrong, who led the project to transcribe the Burgh Records, said the find was ‘very exciting’ and ‘helps us to reframe the early story of Scotch whisky’.

He said: ‘This is the earliest record directly mentioning the apparatus for distilling aquavite, and that equipment was at the heart of renaissance Aberdeen where at this time our own university had just been founded and the educational communities of humanism, science and medicine were growing.

(From left) Dr Jackson Armstrong, Dr Claire Hawes and Phil Astley

‘This find places the development of whisky in the heart of this movement, an interesting counterpoint to the established story of early aquavite in Scotland within the court of King James IV.

‘What is more, some other early references to aquavite refer to the spirit used in the preparation of gunpowder for the king. The Aberdeen still being for aquavite and rose water may suggest, by contrast, that it was for making whisky to drink.’

The modern English word ‘whisky’ comes from the Gaelic ‘uisge beatha’, which also means water of life. It appears in various forms in written records from about the seventeenth century onwards to refer especially to the aquavite made in the largely Gaelic-speaking highlands and islands.

The Aberdeen record shows that the aquavite still was in the hands of a George Barbour at the time of the hearing and he was ordered to hand over possession to Gray’s heir, dean Robert Kervour. According to Dr Hawes’ research this is almost certainly the same man, known as Robert Carver, who would later become a famous choral composer based at the Chapel Royal at Stirling Castle.

She said: ‘Other entries in the archive for George Barbour show that he was active in early medicine in the city while Gray himself had associations with a number of key characters closely linked with learning, science and culture in renaissance Scotland.’

Dr Armstrong added: ‘There are also tantalising suggestions in the records about where the still may have been located. Andrew Gray had property in a street known as Guestrow. In Middle Scots this distinct place name was usually written as “gastraw”, in which “gast” means ghost or wraith. So the very first reference to a whisky still is likely to have been on a street associated with spirits.

‘Today just a small section of Guestrow remains, opposite the bustling Broad Street, and it is home to the appropriately named Illicit Still pub. The name recollects a later age when whisky was crafted for sale undetected by the taxman, but it is possible that its location has a connection to the history of Scotch going back much further.

Phil Astley, Dr Jackson Armstrong and Dr Claire Hawes outside the Illicit Still on Guestrow

‘This is a very significant find in the history of our national drink. It reframes the story of Scotch whisky and suggests new layers of complexity in Scotland’s urban history.’

Researchers have now been awarded £15,000 in funding from Chivas Brothers, which owns some of Scotland’s most famous distilleries including The Glenlivet and Aberlour. That gift will fund new research into the still and associated stories from the Aberdeen Registers Online.

Dr Claire Hawes, who uncovered the record and conducted initial research on the find, said that the support would allow the research team to delve deeper into the archives to uncover further details of origins of whisky in Aberdeen.

She explained: ‘All references to aquavite or whisky from this period are significant because its early development is largely unrecorded.

‘Others such as the first ever reference to malt for the King in 1494 are stand-alone references but what is really exciting here is that it is part of our extensive Burgh Records.

“That means we can trace those involved in the distillation of aquavite throughout the records, looking at their connections, where they lived, their professions and how all of this might be intertwined with the early development of Scotch whisky.

‘This could significantly change our understanding of the origins of our national drink.’

The aquavite entry was found in the Burgh Records of Aberdeen

Alex Robertson, gead of Heritage and Education commented: ‘This is a truly significant and exciting discovery for Scotch whisky. Given Chivas Brothers’ historical ties with Aberdeen, we did not hesitate to lend our support to the furtherance of this important research. The University of Aberdeen’s work will go a long way to build a clearer picture about the origins of the world’s favourite drink, and we look forward to what they discover next.’

City archivist Phil Astley added: ‘This incredible find illustrates what an amazing resource the UNESCO-recognised Aberdeen Burgh Registers are for the study of Scottish urban history. The detailed picture of late-medieval society that emerges from these records is one of a developing social structure increasingly influenced by the cultural, scientific and educational forces of the Renaissance period.’

Karen Betts, chief executive of the Scotch Whisky Association, said: ‘This is an exciting discovery which adds to our understanding of the history of Scotch Whisky distillation.

‘The work that the University of Aberdeen has done to uncover new information about the origins of the industry is particularly timely given the surge in Scotch Whisky distilling in recent years. All new distillers learn their craft from the past, and so ensure that the heritage and traditions of the industry are taken forward into the future.

‘Last year, there were more than 2 million visits to Scotch Whisky distilleries. More and more people are discovering the story of Scotch and this work can only deepen interest in Scotland’s national drink.’

TAGS